News & Articles

Browse all content by date.

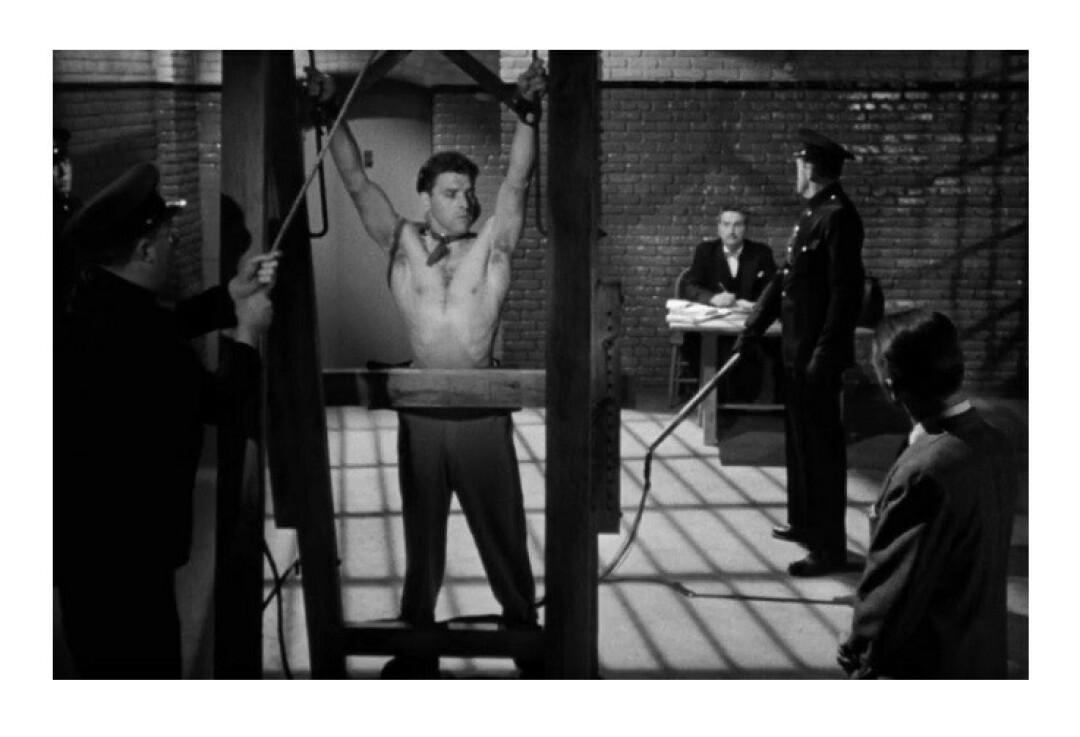

Burt Lancaster is about to receive the judicial corporal punishment of 18 lashes from a cat o'nine tails, an actual form of punishment in British prisons until it was outlawed by Parliament in 1948, the year this movie was made.

Burt Lancaster is about to receive the judicial corporal punishment of 18 lashes from a cat o'nine tails, an actual form of punishment in British prisons until it was outlawed by Parliament in 1948, the year this movie was made.

“The aftermath of war is rubble – the rubble of cities and of men. They are the casualties of pitiless destruction.

The cities can be rebuilt, but the wounds of men, whether of the mind of or the body, heal slowly…”

So begins the written prologue of a tasty little noir that I recently discovered on the Criterion Channel.

I was checking out Criterion’s list of movies that will be leaving at the end of this month. Among them is a collection called Gothic Noir, and in that collection is a 1948 thriller called Kiss the Blood Off My Hands, starring Burt Lancaster and Joan Fontaine.

What? Why have I never heard of this film noir before, especially since I’ve seen every other noir with Lancaster in a brilliant three-year period that began with his 1946 film debut as the Swede in Hemingway’s The Killers, followed by Jules Dassin’s excellent prison film Brute Force, then Lancaster continued the film noir roll in Desert Fury, I Walk Alone, Sorry, Wrong Number and in 1949, both Criss Cross and Rope of Sand.

Well, it turns out that this movie was never available for home viewing until Kino released a Blu-ray edition in 2020, and I’ve read that it made it’s first appearnace on TCM in 2023.

So I was happily surprised to learn about this little gem of a romantic thriller that takes place in post-war foggy old London town. Well, a reasonable facsimile on the Universal-International sound stage of a London still slowly recovering from the wartime blitzes.

Thirty block’s of London’s East End waterfront district were recreated at the studio. The sets fooled me, especially with the presence of the great British actor Robert Newton as a creepy and menacing blackmailer. I can’t recall seeing him in anything but British productions, such as Carol Reed’s Odd Man Out and Hitchccock’s Jamaica Inn (Hitchcock’s last film in England until 1972 when he made the great Frenzy, the penultimate of his more than 50 films).

I learned that after making Kiss the Blood Off My Hands, Newton appeared in several more American films from 1952 to ‘54, including as Etienne Javert in a 1952 production of Les Miserables, as Blackbeard the Pirate in a 1952 Raoul Walsh production and with Richard Burton and James Mason in Robert Wise’s 1953 The Desert Rats, about the combined Aussie-British defense of Tobruk against Rommel’s tanks.

Newton is at his greasy best as the Cockney blackmailer in Kiss the Blood Off My Hands.

Kiss the Blood Off My Hands was the first release by the fledgling Norma Productions, which Lancaster started with his agent, Harold Hecht. The movie was based on a 1940 bestseller with the same odd title, written by Gerald Butler, a crime and pulp writer referred to as the English James M. Cain.

Robert Siodmak, who directed Lancaster in The Killers and earned an Oscar nomination for his efforts, was set to direct Kiss the Blood Off My Hands, but production delays caused a conflict with Siodmak’s schedule, so Norman Foster was brought on board.

Foster was a stage and screen actor before turning to directing and specializing in crime and mystery features, including six of the Mr. Moto films starring Peter Lorre and three Charlie Chan movies. He directed himself in his last starring role, the 1936 I Cover Chinatown, and in 1943 he directed Orson Welles’ Journey Into Fear.

Immediately I was sucked into the story of a guy on the run because he accidentally kills a pub owner. Lancaster is Bill Saunders, a Canadian sailor who is in London after jumping his ship. Along the way we learn he spent two years of the war in a Nazi POW camp, and the experience has left him with a violent temper, the mental wounds referred to in the prologue.

After accidentally killing the publican, watched by a greasy-looking character we later come to know as Harry Carter (Robert Newton), Saunders starts running, chased by locals and eventually a copper on his beat, who is soon joined by a colleague. The chase scene allows Lancaster to exhibit skills from his first career as a circus acrobat. As the two cops search for him among scaffolding next to an apartment house being repaired, Saunders slips through a window and into the room of sleeping nurse Jane Wharton (Joan Fontaine).

Fontaine is a revelation here, so natural and perfect in the role. I’ve never seen her better. It is easy to see how Saunders could fall for her so hard, which he does.

Once the police have stopped searching for him, Saunders finds Jane and invites her to go to the horse races. They have a fine day, but on the train ride home, Saunders becomes enraged by a lecherous salesman. When Saunders slugs the man, Jane polls the emergency brake on the train, and the pair leave the train. Jane is appalled by his violence and says she never wnts to see him again. As he tries to convince her otherwise, a copper shows up, Saunders slugs him too and is finally subdued by a glow to the head from another copper.

Saunders is sentenced to two concurrent six-month sentences for each assault. When the judge also ordered, because of the violence of his actions, 18 lashes from a cat o’ nine tails, I thought, no way. This is not medieval England but mid-20th century England. Surely such a brutal punishment at that point in history is pure movie fantasy.

Much to my surprise, cat o’ nine tail lashings were standard judicial corporal punishments for violent offenders until outlawed by Parliament in 1948, the same year this movie was made and released.

All of this makes me wonder about the 1940 source material, Gerald Butler’s bestselling novel. The lead character of the movie gets into trouble because of his violent reactions, which are blamed on the two years subjected to Nazi cruelty in a POW camp. The original character in the novel must have had another excuse for his violent ways.

After Saunders’ release from prison, the kindly Jane Wharton arranges a job for Saunders as a delivery driver for the clinic where she works. She sees a change in Saunders. He has quelled his desire to punch first and ask questions later, and she sees this in action when he convinces an anti-vax father to let Jane give a shot to his deathly ill daughter without punching the unreasonable dad in the face.

His getting the job brings Harry Carter out of the woodwork. Carter has a plan to hijack Saunders’ truck when it’s full of drugs, and if Saunders doesn’t cooperate, Harry will turn him in for killing the pub owner.

Saunders agrees because he sees no choice, the dilemma of every film noir lead. But on the appointed day, Jane decides to ride shotgun with Saunders, who calls off the plan so Jane won’t be hurt.

Desperate to get his hands on the drugs, Harry pays a visit to Jane and tells her that Saunders killed a man. Things turn ugly, and Jane ends up stabbing Harry. Now both she and Sanders are both responsible for deaths. Saunders wants to deliver a truck full of drugs to a ship captain, who in turn will bring the pair to Spain.

But Jane won’t do it. She wants to turn herself in and plead self defense for killing Harry. She suggests Saunders could do the same. And he says yes. The end.

It may seem like a pretty pat ending, but the two actors are so believably in love that it does not seem implausible that Saunders would want to take his chances with the legal system.

At only 79 minutes long, this is a taut and fun fllm noir. Catch it on Criterion before the end of the month.

| Tweet |