News & Articles

Browse all content by date.

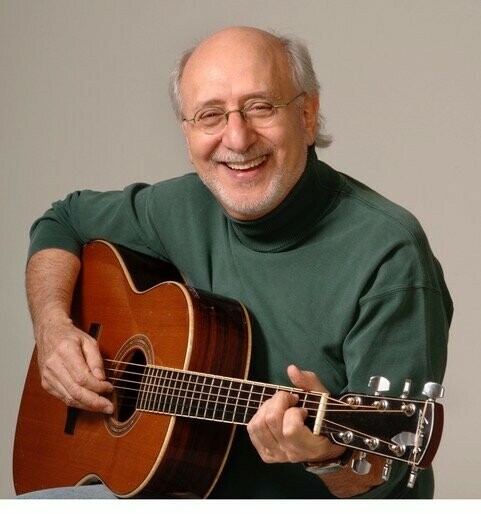

Folk music icon, Peter Yarrow, of the internationally renowned trio Peter Paul and Mary, is coming to the West Theatre on Wednesday, April 10. Babyboomers and the seniors among us undoubtedly know of him, but younger generations may not. Yarrow was born on May 31, 1938, in New York City to Ukrainian Jews who had immigrated to the U.S.

Peter’s formative years were spent in New York and he was active in the Greenwich Village scene during the heyday of the 1960s, where he began performing as a folk singer. He has written numerous songs, both alone and with others—including “Puff the Magic Dragon,” “The Great Mandala” and “Day Is Done.” (This latter song won Modern Parenting’s Parent’s Choice Gold Award in 2009.)

The list of awards, commendations and honorary doctorates bestowed on Yarrow for both his musical and activist works is impressive.

Currently on a limited spring tour, Duluth is his second stop. His son Christopher Yarrow will be accompanying him in this show. I was honored to be able to interview Yarrow and I hope what you read gives you a hint of the profound experience that awaits you if you attend the concert.

JF: What was your early exposure to music?

PY: I was age 8 when saw [the great violinist] Isaac Stern play and I thought I must do that. The next thing I knew I was taking violin lessons. I went up to Chautauqua [New York] where my mother was directing a play (she was an English speech and drama teacher). She got me lessons with the wife of the concert master of the New York Philharmonic Orchestra which was located in Chautauqua during the summers. The concert master was the very, very esteemed and renowned Mischa Mischakoff. His wife was Hortense Mischakoff and I loved it and I loved her. Then in the fall my mother got me lessons an hour away on the subway, near Yankee stadium. But he made me cry every lesson and after a half a year I said I’m not going to do this anymore. My mother being very smart and, knowing I had seen Josh White perform at the YMHA [Young Men’s Hebrew Association], appeared a few months later with a guitar. It wasn’t an adult sized guitar, it was obviously for me. I said, “Oh mom, I want to try that!” She said “No, no, that’s mine.” She waited to let me have it—a Martin guitar which, as we know, is the best acoustic guitar.

There was money for that. There was money for culture. I went to the Leonard Bernstein children’s concert series. I went to the opera when I was that age. I would sit down at the dinner table and listen to WQXR radio, something called the “Dinner Concert.” So I was suffused in culture. It was everything for education, knowledge, learning, so I had some real musical background there, not just as a listener. And you know when you play the violin it really enhances your capacity to hear the pitch because you have to create the pitch.

JF: You mentioned Josh White…

PY: Josh White, the most iconic blues singer, was both an activist and a singer. He was a favorite at the White House and his son’s Godmother was Eleanor Roosevelt. Josh White sang songs like “Strange Fruit.” He was a “left winger” and then he got chased by McCarthy in the McCarthy era. But I knew him and when I was at Cornell [University] I produced a concert for him and he became a friend and a mentor to me. He is an astonishing figure, historically, and a tragic one too. Anyone who was Black was subjected to the House on Un-American Activities Committee. I would say he was a master performer and Pete Seeger was my ideal. Then Theo Bikel, who was like the Jewish Pete Seeger and also a movie star, in the Union, the Screen Actors Guild. He was an activist. So you know I had great influences.

JF: It sounds like social consciousness and music was all intertwined for you.

PY: Well it was. I went to the “Fame School” – the school of music and art—you remember the TV series and movie. I went there as an art student. I painted. I was more in love with painting than I was with music. I was already singing folk songs but I never studied it seriously, I just sponged it from others. JF: I understand you also went to the Interlochen Summer/Music Camp in the Catskills. How old were you then? PY: I was a sophomore in high school. At Interlochen I was in the Festival Chorus and I was in a play called “Tomorrow the World” about Nazism and I was a potter, I made pots. But I was not wanting to study music seriously. To me it was an ideal environment because they had all the departments, all the arts and I could sing; I sang the “Barrio Requiem.” I was just in love with life there and was in love when I was at the [arts and music] high school.

JF: You and I have both spent time in Woodstock and as it happens, your mother’s property, with a derelict cabin there, actually abutted my property and I understand that Bob Dylan spent time with you there.

PY: Yes, I spent summers during my childhood at that cabin, when I was young, after the [my parent’s] divorce. I studied with the wife of Brock Brokenshaw a Woodstock painter, who was something of an artist herself. As the years went on I was an usher at the Woodstock Playhouse, and I continued painting at the Art Students League [of New York, which summered in Woodstock]. Then at the cabin, I brought Bob Dylan up there in 1963 prior to our going to the March on Washington, because it was beastly hot, together with Suze Rotolo, his then beloved. And that’s where he wrote some of his most remarkable songs.

JF: I read that is where he wrote “Only a Pawn In Their Game.”

PY: Yes, the summer of ’63, while I was off to the Art Students’ League.

JF: Have you kept up your painting by the way?

PY: Yes, I do still, but not as avidly because I have a lot on my plate!

JF: And will you be singing some Dyan tunes at your concert?

PY: Of course, I will sing “Blowing in the Wind” and "The Times They Are a-Changin’” along with Seeger’s “If I Had A Hammer,” Woodie Guthrie’s “This Land Is Your Land” and others of that era.

JF: With regards to the folk music of today…how do you view current folk music with your perspective?

PY: Well, it still exists it, it still has a place, but it’s a very minor place compared to pop music. And pop music is, to a large degree, a wasteland. It’s not so with certain artists. I mean Lady Gaga has a hell of a conscience, Alicia Keyes sings about it and she walks the walk and so does Taylor Swift who is a beacon of feminism for teenage girls: Don’t allow the repression that you feel from young men your age to become a reflection of your self-confidence, your essence or self-esteem. Because you are powerful, you are the voice and you can meet them in mutual terrain rather than simply be reactive to the male-dominant culture that we’ve inherited.

JF: I’ve never really listened to Taylor Swift, so I guess I’ll have to do that!

PY: Well, you know it’s not her music, it’s not her singing, they aren’t exceptional or even wonderful, it’s her lyrics and how they can become…like Peter Paul and Mary! Except she isn’t singing to peaceniks, she’s singing to young women who are hopefully not going to allow themselves to be repressed by a male culture of dominance that has brought us to where we are today.

I mean it is the oppressed people of the world—you know the biblical invocation, “the meek shall inherit the earth.” Look who’s strengthening now—the women. Can you imagine what’s has happened with women with the “Pussy March,” etc. etc. I mean, my God, women are showing up and saying “I will not!” And the oppressed! The LGBTQ showed up and the Black community with Black Lives Matter—the first national gathering of a movement that completely blanketed America where the people, instead of saying “where are the people in the streets now that these terrible atrocities have occurred?” The people were in the streets. And also the students! The students who have been organized. Students have been, in their way oppressed. If you have been told not to go to school knowing that there could be a shooter, and let’s rehearse for it. I’m telling you the students are gathering strength.

We are talking about marginalized people coming into their own. Now, while the Trump reality is growing in its metastatic way, we also have the coalescence of those who have been oppressed to feel their strength. And alas, we don’t have music to accompany that the way we did in the Civil Rights and Vietnam War movements. But nevertheless those movements are in progress.

JF: Are you are saying you see the music and social movements sort of separating, where it was more integral in the mid-60s, maybe late 50s?

PY: No, It’s got a smaller impact, a smaller footprint, a smaller place, as far as music is concerned.

JF: I listen to this radio station, “Radio Heartland” and it playa a fair amount of what is termed folk music, including classic folk songs from the 60s and earlier, but most of the music they call folk doesn’t seem to be addressing the same level of global issues.

PY: You are correct. Because that kind of connected consciousness that is the legacy of the Woody Guthries and the Pete Seegars and Peter Paul and Marys and Bob Dylans...the culture has shifted. People don’t trust each other anymore. I mean they do, but it’s diminished, extraordinarily. People are much more inclined to betray each other, people are self-centered, people are far less generous. The shift in the culture has depleted many of the great things that were born in 60s—just plain old kindness, plain old dedication to fairness. But in terms of another level of consciousness, that’s not the basic vocabulary of popular music.

JF: Tell me about the kind of show you will be putting on for us on April 10.

PY: It’s really a remarkable phenomenon because the kind of warmth and enthusiasm and caring that was once just expected and taken for granted, is reignited amongst people when they sing together, songs like Puff the Magic Dragon or Leaving on a Jet Plane. It’s phenomenally moving because it kind of asserts the spirit that bound us together so powerfully so many decades ago and still is in our in our culture and in our hearts and in our DNA. In the era of the animosities of our time, it’s something that’s so restorative to people, so confirmational. No we’re not gone, no we still believe in something together. Yes, we still have positive advocacy. Truth, fact, is not a moving target. There are real facts that exist. We have to understand that the dangerous slide of the culture and politics into this polarized, hate filled perspective is not something that necessarily has to subdue us.

JF: Are you planning to sing my favorite song of yours, “The Great Mandala”?

PY: Oh my God I am so pleased that you asked, I will yes.

JF: I have a couple of Peter Paul and Mary albums and I went online and viewed you performing that song with Richie Havens.

PY: That was on a TV show, early on.

JF: When my partner and I listened to it together, both of us teared up, it was so moving.

PY: Thank you.

JF: Another friend of mine’s favorite is “Stewball.”

PY: That was a great one, it still is great. I love singing it. I will probably do that one too.

JF: I understand that in addition to singing you will also be telling stories during your performance here. PY: I always do. I always perform like a teacher in a sense. My mother was a teacher and so my intention with the music, even from the get-go, was to be able to use it as a tool of creating community and sharing a certain point of view that inspired me and formed me and now, when I’m solo, I’m much more able to just speak improvisationally to the audience about things that are going on. I will talk about today and about my perspective on it.

JF: How do you see music affecting our culture? Do you think there’s really hope?

PY: I do think that music of a certain sort can be a binding force but it’s a matter of the intentions and then the musical form. Pop music now does not do that in general. But you can see that phenomenon very clearly today with Taylor Swift because essentially what her songs are doing are painting a picture of young women who don’t want to be living under the kind of repressive society that is male dominated, socially and culturally. That’s the reason for her success, as far as I’m concerned. It’s because she gives voice to the sense, the desire and the cry for propriety and equality for young women and their male counterparts.

JF: That leads me to ask again about folk music in general. You’ve been there from the early scene back in the 60s. What do you think about how it’s evolved over time and where it’s headed in the future?

PY: We saw the whole folk renaissance that was amazing, that stood on the shoulders of the Weavers and Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie. It was the dominant music form of its time, the mid-60s and then it also influenced the evolution of folk-rock and the Beatles. Prior to that most of the popular music was not substantive or something other than the frivolity of a casual relationship or love, not necessarily frivolity, but about love and dating. Now it’s not used in the same political way. For one thing now there are a 100 different vehicles for getting your music. Back then we could have a song like “If I Had a Hammer” or “Blowing in the Wind” and everyone would know it. But in the past 20 years there is no song whose verses everyone knows, so you can’t have that kind of cross-pollinization with other people with other kinds of music tastes or other ideological or political tastes.

JF: Are you thinking that technology has reduced the effectiveness of folk tunes to enlighten us?

PY: No, no, I think it was on the decline, but it has accelerated the efficacy and the utilization of music as an instrument of organizing and mobilizing for positive change.

JF: A friend told me a story of the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago, that you were there and that you were not allowed to use loudspeakers to project your songs to these crowds, but that you got a bunch of people to join you in singing to overcome that limitation.

PY: Not exactly. I was married to Euguene McCarthy’s niece, that’s where Mary Beth and I met, when we went to the convention—Peter, Paul and Mary went. And Eugene McCarthy was never allowed to speak to the convention because Mayor Daley controlled that and wanted Herbert Humphrey [to be the Democratic presidential nominee]. A demonstration was held in front of the Hilton Hotel, where the campaign headquarters was located and at a certain point they were saying “Delegates if you are with us flash your lights” and a great cry went up from the people. Mary and I both were in tune with that; we went downstairs, Paul hadn’t heard it. We stayed there that night and I sang until it was daylight, just acoustically, and it was kind of a protective capsule for us. Then in the morning Senator McCarthy came out. We had those little speakers you could put on your heads and we sang there together and that’s when he spoke. We had the feeling at the time that democracy was in jeopardy, not like it is now, but in the sense that the democratic process had been interrupted by power politics and backroom decision-making. It was one of the most dramatic turning points in our country’s history because if we had elected Eugene McCarthy, or Robert Kennedy or even Hubert Humphrey (who would have been for peace) that particular schism, which still exists today, would not have had its inherited effect (potentially, managed differently) that is plaguing our nation. It’s the same division now.

JF: That brings to mind the whole Israeli-Hamas debacle. Have you been involved in any of that?

PY: I have. I am desperately pulled apart because of the tragedy on both sides. On Israel’s part, what they are looking at is not the death of some members of their country but the reappearance of the bestiality of the holocaust, deliberately prepared for them with the dismembering, raping, burning. It was not about killing but about atrocities. And it was meant to ignite their response which is hysteria and fear. Look if you’ve been waterboarded in Guantanamo and somebody says “let’s go out for a swim and here’s a board, let’s play this game,” you’d say “no thank you.” There’s an intergenerational memory of trauma that is excruciating. They’re not going to be able to live feeling that there’s a hovering holocaust. And yet, the Hamas, that controls the narrative has created a scenario whereby they have shot themselves in the heart. And now they are doing something that has made Israel an international pariah and excited monumental antisemitism. No matter what, there is no moral equivalency, there’s just the absolute necessity for everyone’s interest to stop it. But Netanyahu, who to my mind is a fascistic guy, very Trumpesque, is still a part of the governing structure in a central way. When the dust settles, the truth of the matter will be what it was before. Unless Hamas is removed from the control of Gaza the Palestinians will never have a two-state solution, they’ll never have an independent state with the PLO. And the only way to get there will be (a very challenging trip of course) is for Hamas to no longer be in power – you can’t kill them of course. What you can do is remove them from control, on behalf of the Palestinians as well as Israelis.

I have been over to Israel many, many times working on the peace movement and have even organized a concert in Ramallah and Jerusalem on two sequential dates, but then it had to be called off because it turned out it was only a few days away from the last Israeli-Gaza/West Bank war. I spent a lot of time figuring out what to do and I have an idea. I am working on something because I want to use music. I found a song recorded in 1978, called "Shalom, Salem Aleicum" by Richie Havens and the French group Les Variations that was piped into Israel, Jordon and Egypt from a radio station on a boat and it became a phenomenal hit in those countries. I think there’s a way to utilize that.

JF: Thank you so much for sharing all this with me. I look forward to meeting you and welcoming you back to Duluth on the 10th!

Because Christopher Yarrow will be with his father at the West Theatre concert, I was able to talk with him as well.

JF: Will you be musically accompanying your father?

CY: Yes. I play washtub bass to hold down the bass line. I took some drum lessons at a kid. I also sing along with my dad and sometimes he’ll have me lead in on a line or together on a verse or two. It’s not orchestrated or choreographed that way, it’s just singing along, playing the instruments, being present in the moment is enough for some musical magic to happen.

JF: Your dad will be telling stories, will you be doing some of that too?

CY: In the past, for a period of about 7 years there, after Mary passed away, when my dad started doing solo concerts he invited me to play along with him, and come join him, especially at solo concerts. I generally have a moment when I introduce myself and will say a couple words. People have gotten to know me just from being there and singing along. During COVID I started taking songwriting classes with a friend, group classes online and wrote some songs. It sounds like my dad has offered me the opportunity to have me play a song—one of those. We just spoke about it yesterday and I’m starting to prepare for that. We’ll see how it works out. There’s the washtub bass I’m traveling with and then whether I’ll have my own guitar. It a different format.

JF: It sounds like you, like your dad, had exposure to music at a young age.

CY: It’s been great singing along with my dad, singing behind him. I’m very familiar with his voice. My dad would come to my elementary school classes and sing for us, so I got used to singing with my dad at an early age. I grew up going to the concerts, I mostly remember the Peter Paul and Mary Reunion tour. I grew up hearing them with an audience and the sounds of the concerts—how they structured the sets and chose the music they did. The audience is really an important part of the concert experience. Lots of people have seen them on TV, at a recorded concert, but seeing them live and singing along is whole other experience.

JF: You didn’t rebel against the folk music genre?

CY: Good question. I got turned onto many different types of music. I did a radio show for three years in college, I got into folk blues and traditional blues, blues artists through taking guitar lessons. I got turned onto some blues artists growing up. I was an MTV baby so I got into pop and top 10 radio music then, through friends, classic rock. I gravitated to the blues, dug a little deeper into that. All sorts of music really.

JF: Opera?

CY: Not really. When I was young I had a high soprano voice and was in a boys choir and did sing a little that might have been operatic. Then my voice changed and I had to refind it.

JF: I’m curious as to whether you would be carrying on the musical tradition of your dad as time goes on.

CY: I am curious about that myself. My sister Bethany Yarrow performs, has a history of recording with my dad, so she has taken up that mantle more than I have. In my time in Portland I have explored ukelele, Ragtime and Americana music. I enjoy that but I’m not sure how it will develop. I’ve not been very ambitious about creating a career. I lost my voice for a number of years and was in my 30s before I started finding what my current voice sounds like. I’ve been gaining confidence with that. Friends and musicians too have complimented me and encouraged me to continue with the music.

JF: You must be very proud of your father, He’s done a lot in terms of activism and raising social consciousness and all that. Is that an area you are at all interested in?

CY: In my own way, yes. I’ve been a part of a business association and have been involved with neighborhood projects. I prefer to work on local community projects and in support of individuals. But I have not been involved in international issues of that type. Affordable housing and fair health insurance, hunger are issues that I’ve been involved with. I’ve been a community organizer, done townhall meetings, always been a part of creating a supportive space for people and trying to do things that match up with my ethos.

JF: Your father is Jewish and has been to Israel. Have you traveled there with him?

CY: Yes, both my sister and I have been with him on a trip there, which has given me some background and understanding of what is happening there now. I’m technically not Jewish, having German and Scandinavian heritage on my mother’s side. She was brought up Catholic. Other than following the Jewish cultural heritage on high holidays and such, I’m not a practicing Jew. I’m a bit of a spiritual orphan. My mother introduced me to Native American ceremonies, in which I learned about prayer. Nature has been my spiritual path, spending time out in the wilderness and loving water, lakes, the Boundary Waters, etc. developed by living in Wilmer, Minnesota, and visiting my grandparents there over the years.

JF: Is there anything else you’d like to say about the upcoming concert event?

CY: My dad is a carrier of hope, it’s such a special thing to share the way he connects with the audience during these concerts.

| Tweet |