News & Articles

Browse all content by date.

One of my first columns for the Reader in 2002 was “You Wanna Fight” about my introduction to Minnesota in seventh grade. I was challenged to a fight and it's one of my favorite stories because in hindsight it seems so Lincolnesque.

While I grappled with Wayne, another kid I’ll call Dizzy was in the circle of cheering boys that surrounded us playing the part of Fox News. While I was in a headlock with Wayne Schultz, the hero of my story, Dizzy was busy trying to kick my family jewels. Dizzy was such a pill that a cousin of his once told me he was embarrassed to share the same name.

Dizzy never bothered me again but I kept a wary eye on him as he spiraled down in life. My Dad told me after I was safely married and living in Duluth that Dizzy had been sent to prison for attempted rape.

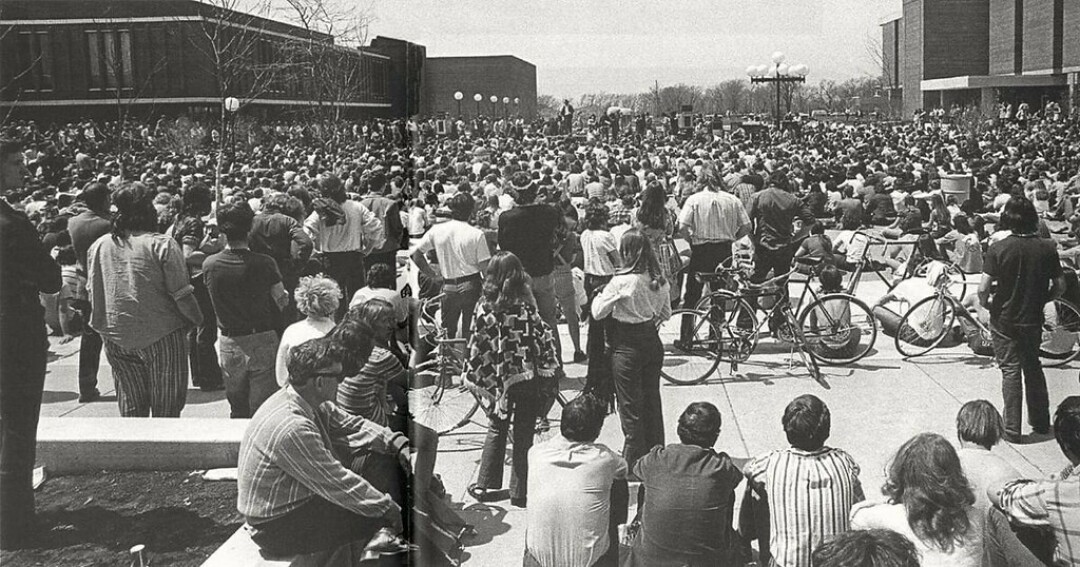

The last time I remember seeing Dizzy, he was walking on the sidewalk near my house on May 9, 1972. He was obviously intoxicated but by what or what combination of things I could only guess. He was heading in the direction of the next day’s headlines – the takeover of Highway 169 by Vietnam War protesters. The blockade was at the junction of Mankato and North Mankato over the Minnesota River.

I was headed uphill to Mankato State’s upper campus, where a short time later I would find myself on the phone with the college intern for Congressman Nelsen, who took up where I left off after my summer with Ancher. She was a saccharine sweet college Republican female version of the Oliphant cartoon character I displayed in my column “1972” a few weeks ago.

I had just parked myself in the Student Senate office where a radio broadcast was describing the kids headed over to block vehicles, including an ambulance at work.

I rather enjoyed relaying the play by play to the serious young woman knowing she would relay the story to the staff I had gotten to know. They were sure to be scandalized by the news, just as they had been outraged at the rude treatment of Senator Goldwater when he answered questions from lefty summer interns.

I didn’t think this protest was too cool. In the Fall of '69 I’d watched an irate motorcycle rider run over the legs of a protester blocking an intersection two blocks shy of the highway. In my view, these actions only served to piss off potential allies. Suspecting that Dizzy was headed there did nothing to reconcile me to the ruckus.

While I was on the phone with Washington a second group of protesters were going to imitate the big leagues, or rather the Ivy league, protesters. They were on their way to take over the office of our college President James Nickerson.

This annoyed me and I decided to inflict a little reverse psychology on them by pulling a Gandhi. When I saw them leave the Student Union I raced ahead of them past a dormitory and parked myself for a lie down on the sidewalk. They would have to step over me on their way to protester nirvana. Several of them made a special point of dragging their feet across my chest. Police who did things like that were often called pigs.

President Nickerson left his office rather than confront the strident heroes. Years later he wrote a book about these turbulent days which I’ve consulted online. Much of it comes from the recollections of dozens of people who experienced the protests from different vantage points.

One of the contributors was the late Larry Spencer, who was the student senate president at the time.

They were all on a speaker phone with Governor Wendell Anderson’s Chief of Staff Tom “I-holiday-in-Las-Vegas-and-always-win-lots-of-money-at-the-tables” Kelm. Kelm scared the bejesus out of just about everybody in St. Paul. He put on a demonstration of aggression with Nickerson and his presidential cabinet, which included Student Senate President Spencer and the faculty union president, my Dad.

I had been listening to the “conservative” Daniel Welty, for years as he cussed out Lyndon Johnson every time more soldiers were sent off to Vietnam.

The call with the Governor’s office was about dealing with the march and the human blockade of Highway 169. Later my Father would fly out to DC to meet with Congressmen Nelsen so as to give him a picture of sentiment on the campus, and while he was at it mention his son the recent intern.

There was more to come for Mankato. Not long afterward someone planted a bomb and destroyed a newly constructed law enforcement center in the city.

On the speaker phone Kelm was channeling Chicago’s hard-ass Mayor Daley as Nickerson’s cabinet argued with him to back off from a confrontation with the students on the Bridge.

Here’s Spencer’s recollection of the call:

“Kelm had another plan in mind and said the governor would not endorse any civil disobedience, and that he was prepared to order out the National Guard to clear the highway and establish order. Dan Welty, a conservative Republican, broke the stunned silence after Kelm’s threat by stating passionately, ‘My God, my son is on that bridge. We will not have another Kent State in Mankato.’”

My Dad was mistaken. I was sure the blockade was going to give the peace movement a black eye with guys like Dizzy drunkenly throwing beer bottles around. I’d just performed my own blockade of the protesters heading to take over Nickerson’s office.

While it wasn’t me who had anything to fear from the Governor’s Chief of Staff my future wife was in harm’s way. She had left Mankato High in high dudgeon over the war. She would have been in the line of fire.

Next week: The next day, May 10, and my kind of protest march.

Harry Welty does this and that at lincolndemocrat.com

| Tweet |