News & Articles

Browse all content by date.

Richard Charbonneau dominated NHRA stock drag-racing competition for more than a decade.

About a year and half ago, I was sitting in my favorite recliner, contemplating what a beautiful day it was, and pondering all the cars I’d driven, car-folks, and race drivers and all the other athletes that made up my world of journalism during 31 years at the Minneapolis Tribune, and the more recent 20-some years back home in Duluth.

I was also thinking how lucky I’ve been, with a great family and a house that my wife, Joan, and I designed and had pretty much custom built on the same ground where I grew up.

Then the doorbell rang at the Gilbert Compound, and almost as if by script, I answered it to see a familiar face from out of the past. It was Richard Charbonneau — a brilliant former drag-racer and engineer who never saw anything mechanical that he couldn’t make function better.

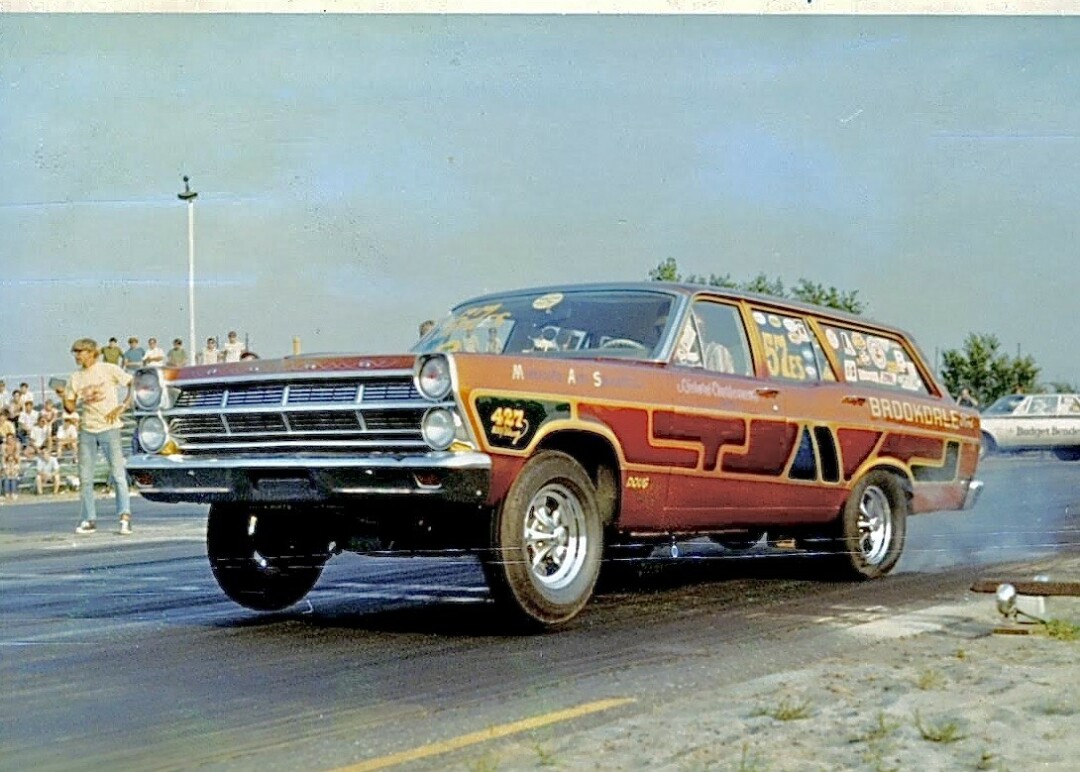

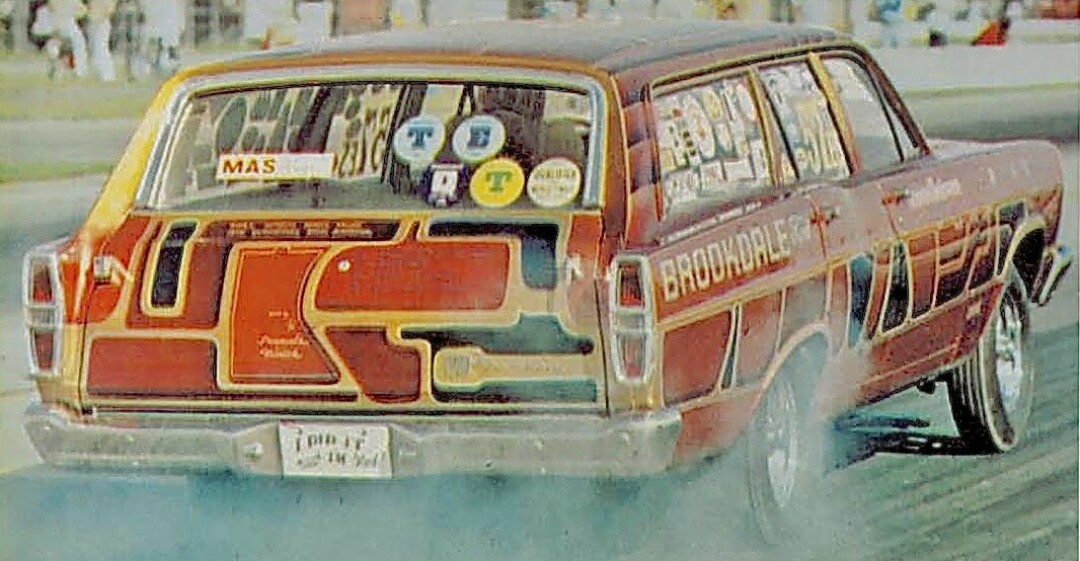

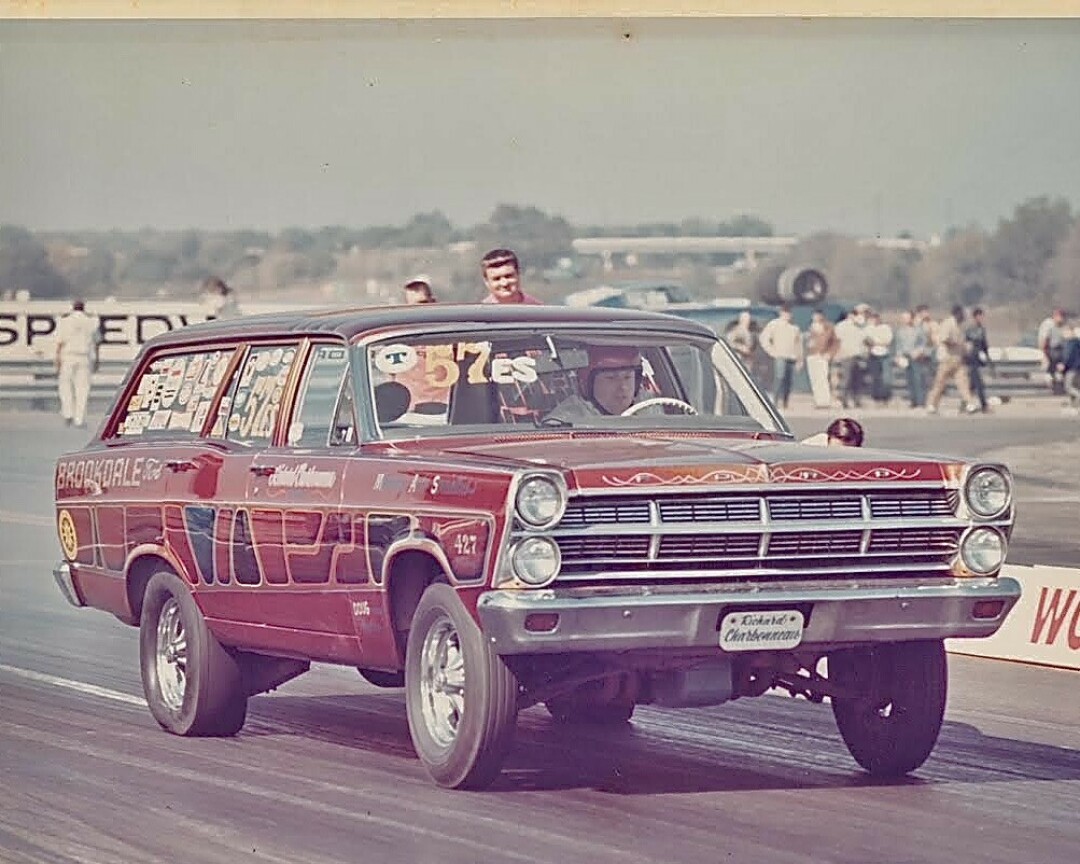

Richard, who I previously knew as “Dick,” always won when it came to hustling a car down the quarter-mile strips of this country. It didn’t matter whether the NHRA meet was at Minnesota Dragways in Coon Rapids, Twin City Speedway in New Brighton, or later, Donnybrooke Speedway (later Brainerd International Raceway) in Brainerd, or more exotic locations such as Pomona, Indianapolis, or any other spot, Richard would roll out his 1967 Ford Fairlane station wagon, painted in elaborate air-brushed patterns of multiple colors.

Nobody who was serious about drag-racing drove a station wagon but Richard was serious, and it didn’t take long before those in the Stock and Super Stock classes knew trouble was coming as soon as he unloaded that wagon. He always won. And he stayed in the Super Stock class where handicapping was key.

He won 20 NHRA event titles, 12 NHRA national class championships, and set 16 national records en route to three Division 5 point titles. When I went to the door and let him in, he walked around and complimented us on our house, and we sat down to have a thoroughly enjoyable conversation.

I had enjoyed many conversations with Dick, and we often disagreed on NHRA policies, or other racing technicalities, but the difference was that I never knew if Dick accepted anything I said as accurate, and he also retained a somewhat distant attitude that made me wonder about his brilliance. When it came to the drag-racing strips around the country, however, there was no question.

When I first started sportswriting at the Minneapolis Tribune, I was drawn to the paved asphalt oval stock car tracks at Elko and Raceway Park in the south and Twin City Speedway in New Brighton, and on Sundays, I was off to Minnesota Drag ways in Coon Rapids where all the hot-rodder in the Upper Midwest gathered to try their hand at beating their buddies. Warren Johnson got his start there, and so did Tom Hoover, Bill Schifsky, and John Hagen, as well as Richjard Charbonneau.

One time, while watching him race at Brainerd, I watched closely because it is difficult to tell who wins at the finish of a drag race when you’re watching from the start. Just before he hit the finish line, I noticed the brake lights blink on Richard’s car. “What the heck was that” I asked him.

He explained the whole concept of bracket racing, where Stock and Super Stock cars are handicapped by their finishing times, so it is beneficial to win, but to win close. There’s no need to rub it in, he explained, and, in fact, if you know you’ve got your opponent covered, you can tap the brakes to slow abruptly and still finish with the win. Brilliant!

Richard was five months older than I am, which I found out that afternoon at my house, when he said, “I’m 79, and looking ahead to turning 80, and I realized that we all go through our lives so fast, the time just speeds past, and then we die. So it occurred to me that I’m going to make an effort to look for and find old friends who maybe I’ve lost contact with, and re-engage. It’s time we start appreciating things we’ve got before it’s too late and we’re gone.”

Charbonneau's unusual but striking Ford station wagon became known nationwide at major NHJRA events.

At that time, Richard didn’t know that only a few months before that meeting I had been knocked down by an unexplained and sudden cardiac arrest while track testing new vehicles at the Road America track at Elkhart Lake, Wis. Despite a clear bill of health from a recent thorough checkup, I felt a sudden shortness of breath, dropped to one knee as if I were in the on-deck circle, and within one minute I was in an ambulance at the Road America track. They got an oxygen mask on me, and off we went, headed west to Fond du Lac, Wis., and a wonderful modern hospital. My older son, Jack, followed. It was there doctors decided they needed to insert stents in three of my arteries, one of which was totally blocked.

I knew none of this, of course, and when I woke up, both our sons and my wife, Joan, were there. I immediately thought it must be the next morning. Wrong. It was six days later. In those six days, I lost 45 pounds and had no interest in food. Doctors were astounded that everything seemed to start working again in my battered system. One, who said he had worked on me in ER, said, “I never thought I’d see you like this.” I said, “Like what?” And he said, “Alive.”

Anyway, Richard seemed genuinely pleased to have stopped at our house for the first time ever, on his way to his usual destination of in-laws’ farm, so he could play with the implements. And he stressed that my close call was just more reason why his new crusade of finding and reconnecting with old friends was the most important objective in his life.

Years ago, when I was just getting to know Richard out in the pits of Minnesota Dragways, I was also familiar with an avid Gopher hockey fan, named Elizabeth. Always friendly and upbeat, I was blown away one day when I saw Richard and Elizabeth, and I realized I knew both of them before they had ever met each other.

Richard was never an avid hockey fan — even though he graduated from St. Paul Johnson in 1960 — but Liz made up for that. They were married in 1975, and as if to celebrate the arrival of daughter Jenelle in 1980 and son Matt in 1983, Liz talked Dick into purchasing the Strauss Skates and Bicycles shop in Maplewood. That, too, surprised me, but Dick kept the hard-working crew that was there, and took his time learning the business.

Our older son, Jack, worked at Strauss for a brief time after Richard and Liz bought the place. First off, as a hockey player, Jack knew Strauss did the best job in the Twin Cities at sharpening skates. That wasn’t good enough for Richard, who looked at the somewhat archaic contraption that contemporary skate-sharpeners were, and he collaborated with an area machine shop guy and they redesigned it. Suddenly, Strauss could offer a treatment on the Strauss Rocker — a multi-radius sharpening device that was a clear advancement in sharpening skates.

Since that wonderful afternoon conversation, I’ve continued to think that whenever I get back down to the Twin Cities, I’ve got to stop by Strauss and say hello to Dick and Liz. It was on Wednesday of this week, while perusing the great new Minnesota Hockey magazine online website, that I spotted a piece about “Remembering Richard.”

Starting out at Minnesota Dragways, Twin City Speedway and then Donnybrooke and BIR, Charbonneau had the field covered.

To my horror, I looked and found that my good friend Richard Charonneau had died earlier this week at age 81. I learned about it too late to get down for the service or the funeral, but I was able to get through to Liz by telephone. It turns out that just over a year ago, Richard learned that he had been stricken with advanced stage pancreatic cancer. They tried everything, all the advanced techniques of radiation, chemotherapy, visits to the Mayo Clinic, but it was too late.

Richard and Liz had pretty much turned the business operation over to the family, particularly daughter Jenelle and her husband Shaun. When I told Shaun about Richard stopping at our house in Duluth for a visit, he said that it didn’t surprise him, because Richard had taken a lot of time to do a thorough job of finding and reacquainting with old friends, and neither of us knows whether he knew of his diagnosis at the time he stopped at the Gilbert Compound.

Richard had sold his station wagon to a fellow who had it custom painted candy-apple red, but another long-time friend, Dean Carlson, bought it back and had it painstakingly restored to the multi-color panels of the original, and the car was trucked out to Pomona to make a stand at the NHRA Museum for several months.

“This last year or so, Richard took a lot of time finding old friends,” said Shaun. “He and Liz loved nothing better than to spend time with each other and their kids and grand-kids. And they got a chance to take an Alaska cruise in August.” When I talked to Liz, I told her about how often Dick and I discussed things, and once I told him how impressive a new Toyota vehicle — a 240Z sports car — seemed to be. It was a big surprise to me when they bought one, and I told Liz I guess he did believe my opinion sometimes.

“And we’ve still got the car,” Liz said, “a 240Z 2-plus-2.” Amazing.

Although it will be hard to imagine Richard driving anything but that tire-smoking Ford Fairlane wagon with the colorful and unique paint job.

| Tweet |