News & Articles

Browse all content by date.

I recently came on a letter sent home by a U.S. soldier on the Anzio front in Italy.

I can’t say if the writer was typical or not, but because the letter is typed I’d suppose the writer was a junior grade officer in signals or other similar department. Because the writer knew he’d be censored he referred his family to a recent Life magazine article that gave more detail then he’d be allowed to give.

Isn’t that interesting? Not subject to censoring, the weather and how the fields looked was a large part of the letter. Maybe the writer had an agricultural background.

In any case, he and others around him rejoiced when a chicken got tangle in razor wire or a cow met a land mine. Incidents such as that meant a welcome break in “chow.”

The letter spends some time on soldier lingo used for the enemy. At the time the German military was stepping in to hold Italy for the fascist cause, so terminology was mainly directed at the Kraut as being the simplest designation.

But wait. Why do I speak when I can give a portion of the letter below?

“A new name for the Germans is coming more and more into use hereabouts. The name ‘Jerry’ a lot of the guys feel is too sentimental. ‘Bosche’ is dated. ‘Enemy’ too impersonal. We’re starting to call them just plain ‘Kraut.’ Thus a fellow on an OP will phone in: ‘There’s a lot of Kraut out here, Sergeant.’ That word seems to convey just the right shade of distaste for something which needs cleaning up.”

The letter closes with this. “…little things that remind me how unnatural this business of modern war really is and how desperately we’ve got to fight to get the damned thing over.”

Bear in mind that the Anzio front was a difficult and dangerous one where the enemy was intent on killing you if they could. In that situation would you have been any more or less sympathetic of the Kraut?

However you or I might react if in a similar situation, one thing lacking in this soldier’s letter is animosity. Beyond cleaning them up to “get the damned thing over,” he doesn’t show signs of hating the enemy Kraut. Is this anonymous (typed on paper gone brittle-brown with age, the letter is unsigned) letter typical of soldier attitudes in February of 1944? I’d suspect so and am rather relieved to see so little hate expressed.

Maybe it’s the case that in an actual life–death situation any excess of emotion gets in the way of survival. Energy poured into hate would take away from getting “the damned thing over.” That’s my view.

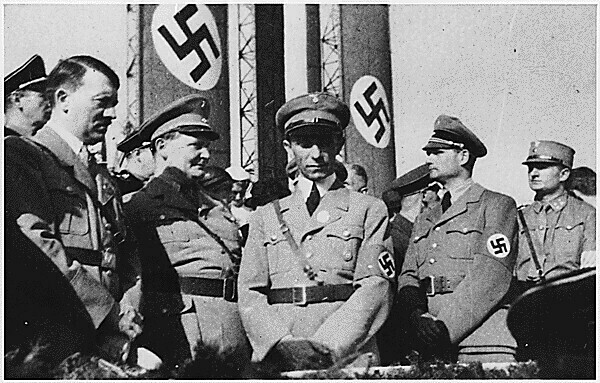

It does seem of interest that those militarily confronting the enemy in Italy don’t seem to dwell on the Kraut being objectionable as a Nazi or Fascist. National Socialist (Nazism) and Union of Soviet Socialists began WWII for ostensible political reasons; that of spreading socialism to other nations, by force if necessary.

Both German and Soviet forces kept political officers in the ranks to monitor and/or enforce obedience to party orthodoxy. In both nations the “people” had to be of one mind. Having other ideas made you a people’s enemy. Review of the matter says the political officers were a detriment to morale and performance by increasing distrust. Makes sense.

If the U.S. soldier’s letter is representative it might show the advantage in allowing those taking the heat to decide for and among themselves how to view the enemy and their task.

I have to contrast the tone and contents of the letter with the tone and content of recent (I’ll call them) political officers intent on monitoring and enforcing political orthodoxy. Those doing so are not ranking officers in a military system, but they do seem to follow a strict view of what is permitted and what isn’t.

At times, not that all would be aware of it, the contemporary political officer can come up with some very amusing things (at which, if they had their way, we dare not laugh). The political One-Mind seeks obedience and will go to lengths to make its point.

I noted that a few years ago when a much regarded national magazine featured an author in a near-frenzy of hate at the Nazis in Poland who marched carrying flags to their border. There, in the author’s eyes, was the taint of fascism.

Rather a pot to kettle thing in my view, but the author was adamant about the danger of this despicable fascist enemy. The writer’s seriousness made the political statement all the more (to me) funny as hell. Why?

Firstly, it was Poland who was the first target of fascist socialism (typically combined in practice, so I state them so). WWII began with socialist forces bringing forced conversion to an independent republic.

These notions can be expressed in various ways, but I think I can defend military invasion as forced conversion. But what were these supposed modern-day Nazi fascists doing that so upset the author?

For one they carried flags representing their nation. A part of the one-mind very much dislikes national flags. (The red banner should represent all.)

The other thing the marchers did going to their border was pray. (The one-mind sees prayer (and possibly meditation too) as mental opium. The one-mind legalizes drugs – criminalizes prayer.

If you wanted to find a thing distinctly un-Nazi you could hardly do better than people, out of humility, praying the rosary to seek guidance and show solidarity. (Remember Solidarity was the movement that ended fascist-socialism in Poland.)

Yet with one-mind conviction and full sincerity an author assured their readers there were hordes of rosary-carrying fascists on the march, ready to swarm over the one-mind with their cursed solidarity and simple faith. (Ironic the author facing no threat was more hyperbolic-dramatic than the solider.)

A part of me says the rosary carriers and the U.S. soldier held simple faith in common.

What? To face opposition in order to be granted a time of peace before then next challenge, which may pose as peaceful.

To the one-mind Nazism is a fortunate mystery.

| Tweet |