News & Articles

Browse all content by date.

From the very first “Ah” you know where you are and where you will be going sonically with “Crimson and Clover,” the late 1968 smash hit by Tommy James and the Shondells, who, with the album of the same title, were making the great leap forward from a bubblegum pops single Teen Beat phenomenon to the logical progression at the time – psychedelic rock that could still be played on pop radio.

After the success of the band with hits such as “I Think We’re Alone Now” and “Mony, Mony,” Roulette Records gave the ambitious young Tommy James free rein when he said he wanted to go in a new direction. A new 16-track recording system allowed James and the band to experiment and explore in this brand-new territory of psychedelia.

And it turned out to be very wise of Roulette to put their trust in Tommy and the band. They knocked it out of the park with a global No. 1 hit in “Crimson and Clover” (except in the UK, where, oddly, it failed to chart!).

It was the perfect ear candy for the time, and it remains extremely tasty to this day.

And then there is perhaps one of the most beautiful songs ever in “Crystal Blue Persuasion.” Tommy will tell you he was becoming a Christian at the time, and the song reflects that. Sure, it’s there. But, I did not know that at the time, and I certainly thought it was a drug reference. Apparently so too did the makers of Breaking Bad, who used it in the soundtrack about a high school chemistry teacher who made a coveted type of potent blue methamphetamine.

No matter. It remains for me a song that lifts the heart and spirits.

I love the jazzy ending of “Crystal Blue Persuasion,” and there are jazz influences elsewhere in this band’s work – the high trumpet in “Sweet Cherry Wine,” for example.

But there are so many sonic treasures in the band’s output, which is amazing when you think about the hit that made everything happen in 1966, that ultimate garage rocker “Hanky Panky.”

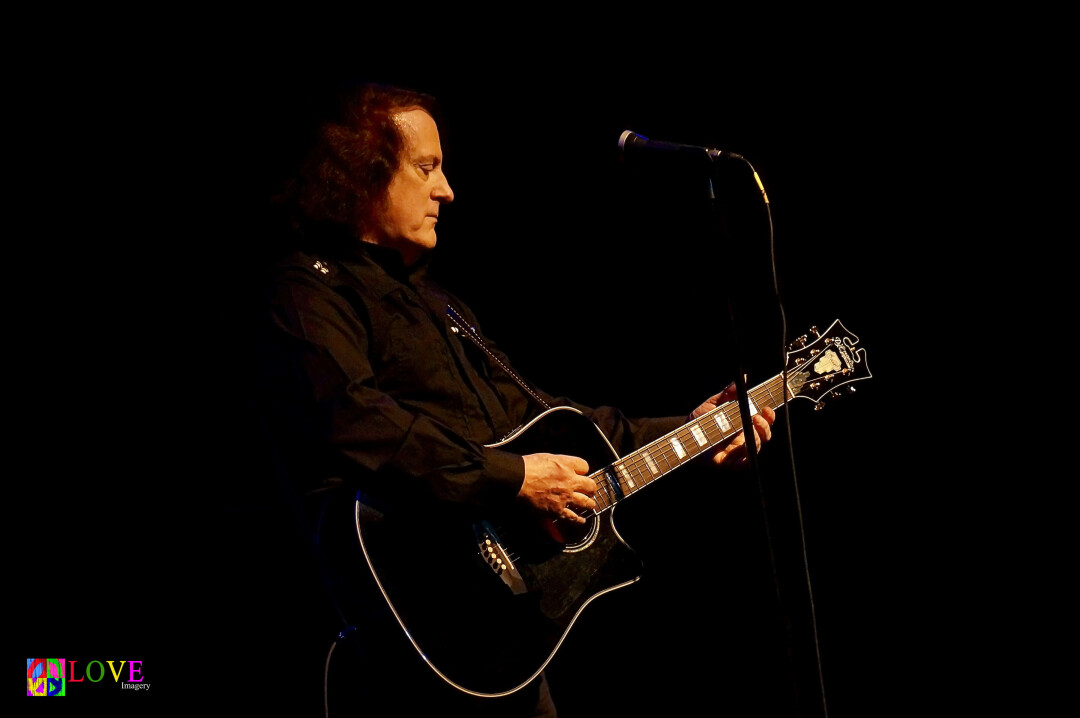

The sonic leap forward seems amazing to me, so I decided I would ask Tommy James how that came about when we talked to preview his Saturday, Oct. 22 show at the Medina Entertainment Center in Medina, Minn.

“Well, there were several things going on,” Tommy said. “One is, of course, music was changing drastically. There were so many changes between ‘63 and ‘66, you know, the British invasion and everything. When I made ‘Hanky Panky’ [that, in itself is a fascinating story that we did not have space to explore here, but, basically, as Tommy, a native of Niles, Mich., has said: “One night I was playing for 20 drunks in a bar in Michigan, and the next night I’m playing for 10,000 screaming fans in Pittsburgh. It was literally overnight. It was very unexpected, one of those winning-the-lottery type stories.”], and it became a hit in ‘66, And then between ‘66 and ‘69, when ‘Crystal Blue’ came out, there were tremendous changes, you know, psychedelic rock came in, the FM stations came in, albums rather than singles. And then personally, I grew up a little bit, I became a Christian. I’ve always thought that as an artist, you record snapshots of where you’re at, at the time. And that was where I was at, personally. So just a whole lot of changes happened. And fortunately, thank God, we had the attention of the public and radio for all those years, because you know, we were allowed to sort of morph into whatever we could become. A lot of groups didn’t have that option and sort of got pigeonholed. Because we kept having hits, we were allowed to change and go through the metamorphosis that we went through. So I’ve always been very grateful for that.”

In 2011, after many of the principals had shuffled off this mortal coil, Scribner published Tommy’s memoir Me, the Mob, and the Music: One Helluva Ride with Tommy James & The Shondells. It tells the story of being signed to Roulette Records, which was a front for the Genovese crime family.

I mention that when I interview-ed one of his pals and musical collaborators, Kenny Laguna, around the turn of the century, the first thing Kenny said was, “I miss the days when the mob ran the music industry.”

Tommy laughed. “That’s because he wasn’t signed to their label.”

After “Hanky Panky” became a regional hit, all the major labels wanted to sink their claws into Tommy James and the Shondells, but Morris Levy of Roulette strongly discouraged anyone else from pursuing them, and everyone listened to Morris Levy.

While that may sound like a stultifying position for a creative person to be in – working for a mob-controlled business – Tommy believes Tommy James and the Shondells could easily have become a one-hit wonder and faded into obscurity under direction of one of the major labels.

“Yeah, well, you know, I’ve often thought, if we had gone with one of the big corporate labels – because we got a yes from CBS, we got a yes from RCA when we were peddling ‘Hanky Panky.’ We got a yes from Atlantic and Kama Sutra and all the big labels. If we had gone with one of them, I doubt we’d have had any of the success that we had at Roulette. And the reason is because we would have had so much competition. ‘Hanky Panky’ is our first record and it was such a fluke to begin with. We would have been lucky to have been a one-hit wonder. Roulette actually needed us. Roulette was a functioning record company and a pretty good one, of course, also a front for the Genovese crime family in New York.

“Honestly, you know, we had 23 gold singles there,” Tommy continued. “We had nine platinum albums, gold and platinum albums, and we sold 110 million records at Roulette. So, we couldn’t have asked for a better situation. We ran the place. I would have never learned what I learned about the record business anyplace else. At Columbia we would have been immediately turned over to in-house producer and an A&R guy, you know, and that’s probably the last time anybody ever thought they needed us. I was really forced to grow up and learn the business. From songwriting and producing to album cover design and stuff, you know?

“And so, from a creative standpoint, we couldn’t have been better. There’s no other way that would have happened except on the job training.”

Were there any downsides to working for the mob?

“Getting paid was ridiculous,” Tommy said. “Crime doesn’t pay, you know. Morris Levy trusted me with all the budgets and everything and bringing people in, and I spent a lot of money, but not much of it was handed to me. Oh, he bought me a farm in upstate New York and if I wanted cash, he would stuff a check in my hand, but regular royalties, we’re just not going to get mechanical royalties. It’s just not going to happen. Of course, we are making money from other things – from concerts, being on the road, and BMI and the writing monies and so forth, but mechanical royalties were just not going to happen. And they let us know, right up front, that if we bitched too much about it, it could be dangerous. So we had to constantly make the decision whether to stay. Because we were having such success with the records, we decided to stick it out, whatever. And I’m glad we did. I mean, we ended up making the right decision.”

Look for the story of those days in a movie theater near you in the not-too-distant future.

“Barbara De Fina is producing the film,” Tommy said. “She produced Goodfellas and Casino and Hugo, with Martin Scorsese. She’s got a string of great movies going back to the ‘80s with The Grifters and The Color of Money with Paul Newman. She’s a great producer. Matthew Stone (also responsible for the 2003 Coen Brothers’ Intolerable Cruelty) did the screenplay. And Kathleen Marshall (Madison-born choreographer and director) is directing. And so they’re working on the cast now.”

It has to be asked. Who would he like to see play Tommy James?

“Well, you know, the funny part is I really have to leave that up to the grownups because there are so many young actors who are good now and you don’t want to you know, it’s got to be somebody who’s also a musician,” Tommy said. “I’m amazed at how many of the young actors started out in rock bands. Jamie Foxx sort of raised the bar when they did the movie Ray. Because he did his own vocals and sounded like Ray Charles. And so he really raised the bar, you can’t lip sync anymore, and you can’t fake the people out. And it’s also very important to use equipment that was actually being used in those years when there’s studio shots, because, believe me, there’s so many geeks out there that will immediately know, that wasn’t available until ‘82.”

Tommy has had a long connection to Minnesota (see the sidebar about supporting Vice President Hubert Humphrey during the 1968 presidential campaign), and admits, “I love playing Minnesota. They do know how to rock out there. Minnesota fans are very loyal and they’ve been very good to us over the years. We’ve played a lot in Minnesota over the years. And we’re going to, we’re going to have a good time, I can tell you that. I’m really looking forward to it.”

If you can’t make Saturday’s show, you can catch Tommy weekly in his Sirius XM show Getting Together, broadcast on 60s Gold, Channel 73.

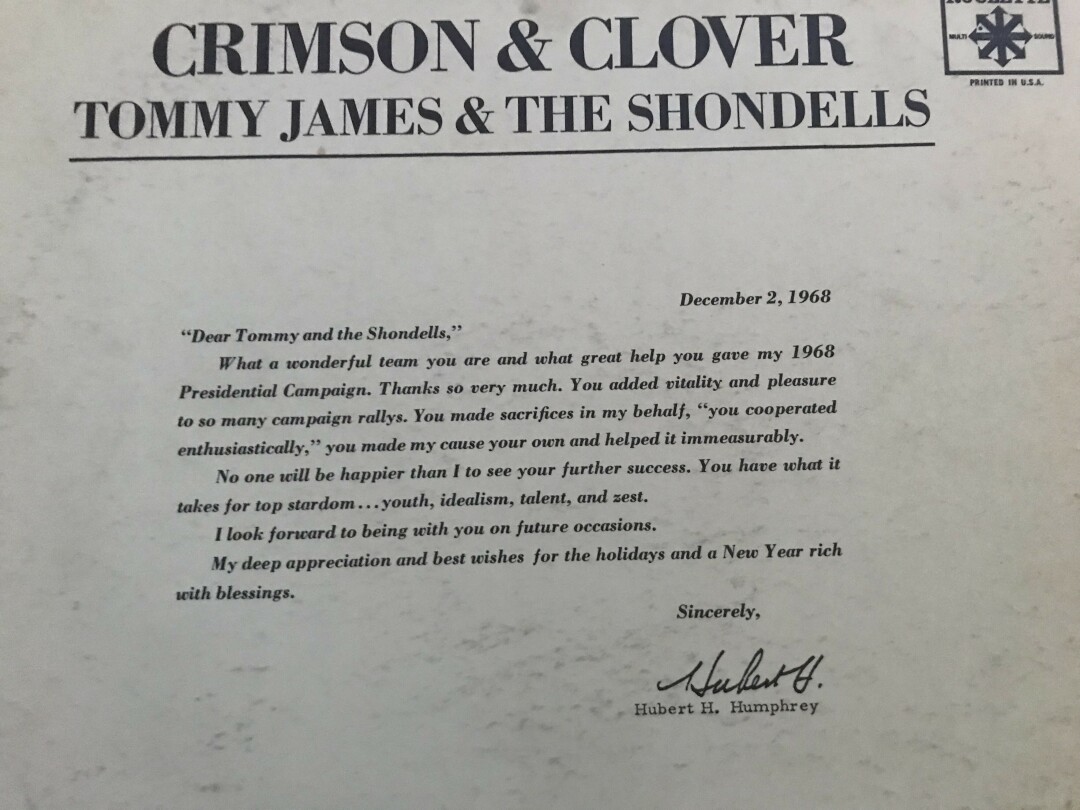

Thrust into history during the 1968 presidential campaign

Besides being filled with great music, the 1969 Crimson and Clover album by Tommy James & the Shondells have historic liner notes written by Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey just a month after a disappointing loss to Richard Nixon to become the next president of the United States.

“We were asked by Hubert Humphrey if we would join him on the ’68 campaign,” Tommy said. “It’s the first time a rock act and a politician ever got together, and we became good friends, of course, as good friend as you can become with the Vice President, when you’re 21 years old. And so before the campaign was over, he asked me to be President’s Adviser on Youth Affairs. And I joked, ‘Believe me, Mr. Humphrey, the youth are definitely having affairs, and I’m just the boy to look into them.’ He thought that was funny. We ended up doing the whole campaign with him. And then of course, he ended up doing commercials for us, he did the liner notes to the Crimson and Clover album. He was just very, very gracious to us. And we remained friends right until he died.”

Was he aware at the time about why the Humphrey campaign wanted them in particular?

“Well, I think it had to be a political decision that we were sort of in the middle of the road between pop and whatever was getting heavy FM play. We were on the radio constantly, so I think it was just sort of a calculated decision at first. But once we got together and did a couple of rallies together, and we would draw a lot of people. He and his people probably sized up the whole situation and said, ‘Yeah, this is working.’”

And, of course, to an ambitious young man it was thrilling to be in the middle of all that.

“I guess you could call it the most one of the most important, exciting and probably tumultuous presidential races in history,” Tommy said. “I was very happy that we were historically right in the middle of all that.”

He and the band were with Humphrey election night at the Leamington Hotel in Minneapolis, watching results slowly roll in on the three networks. Eventually, Humphrey left for his own room.

“When he went up to his room, he had a slight lead,” Tommy said. “And all of a sudden at 5 o’clock in the morning, the voting machines broke down in in Chicago. Mayor Daley in Chicago was still upset with Humphrey and the Democrats for making him look bad at the convention. And so the voting machines just mysteriously broke down in Cook County and in Chicago, and suddenly, about 7 o’clock, they came rushing back on. And guess what, Nixon won. And, of course, everybody thought that, you know, Daley had swung the election like he’d done so many times before, against the Democrats. And everybody wanted Hubert Humphrey to do a recount. He wouldn’t do it. He said, nope, nope. The country has been through enough. He says, Nixon is the President. That’s what he said. And then he said at breakfast the next day, [Tommy breaks into a very passable Hubert Humphrey voice, which was very distinct] ‘You got to watch this fella. He has a habit of getting himself in trouble.’ He said that.”

And had Humphrey won, would Tommy have retained the title of Presidential Adviser on Youth Affairs?

“Who knows? Maybe my life would have gone in another direction,” he said. “But I was very proud to have him as a friend. He was a wonderful man.

| Tweet |