News & Articles

Browse all content by date.

This winter has been good for sitting by the fire with a good book. It has been colder than recent years. The skiing conditions have been good but temperatures have made reading inside appealing.

Two especially good books are appropriate for the times. With the current wave of un-American attacks on teaching accurate history these two books are essential reading.

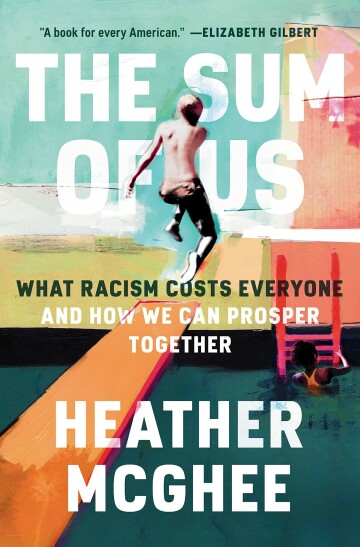

One cannot understand the role of race in American history without reading these books. I refer to Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents by Isabel Wilkerson, and The Sum of Us: What Racism Costs Everyone and How We Can Prosper Together by Heather McGhee.

In Caste, Ms. Wilkerson asserts that the United States has a caste system similar to that of India. This ranking of people is based on skin color and puts whites of European decent at the top. Other people of color are ranked by closeness to being white with Blacks at the bottom. Native Americans, Hispanics and Asians have an assigned rank. Even white immigrants are looked down on until they assimilate.

The caste system is largely unseen, unconscious and unacknowledged. The caste system is more ingrained than just the racism, prejudice and discrimination most people recognize. It is more than class or economic status. The caste system shapes many legal, economic and social relationships in American society.

She documents this thesis with sociological research and historical events. Most compelling are the stories she tells about real people and her own experiences as a Black professional woman. She shows how our lives today are defined by the ranking and division of caste.

There is much more to this book than I can adequately summarize in this article. Instead I offer a few topics discussed in the book that struck a chord with this old white guy.

One of the reasons the caste system and racism continue is the misinformation Americans get from the news media. Ms. Wilkerson says “news outlets feed audiences a diet of inner-city crime and poverty so out of proportion to the numbers that they distort perceptions of African Americans and of social issues as a whole.”

For example, only 22% of of African Americans are poor. Blacks are only 27% of the poor population in America. But Blacks make up 59% of poor people shown on the news.

White families are 66% of the poor but are shown in the news only 17% of the time. Black on white crime suspects are 10% of serious crimes but these cases make up 42% of crimes in the news. These disparities reinforce racial stereotypes common to caste systems.

The election of President Obama is suppose to have marked the end of racial prejudice. But as Ms. Wilkerson writes, “Obama’s victory did not occur because most voters in the dominant caste had become more open-minded...the majority of white Americans did not vote for the country’s first Black president.”

Only 43% of whites voted for him in 2008 and 39% in 2012. In Mississippi 10% of whites voted for Obama. Racism and a caste system that establishes everyone’s “place” in society is still alive and well.

The election of Trump happened because of a white backlash. Much has been written about why rural whites voting for Trump and other Republicans against their own economic interests. But many Trump voters were educated, middle and upper class. This is sometimes explained as the “politics of resentment.”

But Ms. Wilkerson ascribes it to caste. Trump’s election wasn’t a result of the economics of poor white dissatisfaction. Rather, “Consciously or not, many white voters are seeking to reassert a racial order in which their group is firmly on top.” Most whites voted their caste.

In summary Ms. Wilkerson says “Caste does not explain everything in American life, but no aspect of American life can be fully understood without considering caste and embedded hierarchy.”

The Sum of Us begins with a question, “Why can’t we have good things?” Ms. McGhee is referring to things like roads, well funded schools, clean air and water, affordable health care, decent housing, secure retirements and family-supporting jobs. Her answer is that too many people in America would rather deny themselves than share with others – especially others of color.

Ms. McGhee cites the historical example of public swimming pools as a metaphor for our national unwillingness to do good things and create a more equal society. Many communities used to have nice public swimming pools. But even in northern communities these were segregated facilities.

When civil rights laws ended segregation many communities closed the public pools rather than integrate them. Ms. McGhee says this “draining the pool” mentality dominates conservative political thinking and is behind opposition to many government social services.

She says this zero-sum thinking (for one to win someone else must lose) is the reason we do not have an efficient national healthcare system, well funded public schools, more union membership, better environmental protection or a truly democratic society with well protected voting rights.

As a result everyone is worse off. We all could benefit from a “solidarity dividend” but are prevented from making progress by the legacy of racism. Too many people believe that the “undeserving” (i.e., minorities and immigrants) are getting ahead at the expense of real Americans.

This toxic rugged individualism and a zero-sum mentality is sustained by racism.

Using history, social research and the stories of people from all over the country, Ms. McGhee makes a powerful argument that racism is hurting everyone. She says, “We suffer because our society was raised deficient in social solidarity.”

An example is our public schools. Because property taxes fund public schools, there is a wide variation in funding between school districts. Racial discrimination, “red lining” in real estate sales and inequality in government mortgage programs resulted in segregated schools which continue today despite legal prohibitions.

Many parents believe their mostly white suburban schools are better. But Ms. McGhee cites evidence that integrated schools actually produce better educated students that are better prepared for the diverse, multicultural real world.

In the end Ms. McGhee is optimistic. The racial zero-sum paradigm is “counterproductive” and “a lie.” But not everyone is buying into it. People are finding cross racial solidarity and achieving change. She says “I know that decisions made the world as it is and that better decisions can change it.”

Being less optimistic, I would hope you have a chance to read these books before they are banned or burned.

| Tweet |