News & Articles

Browse all content by date.

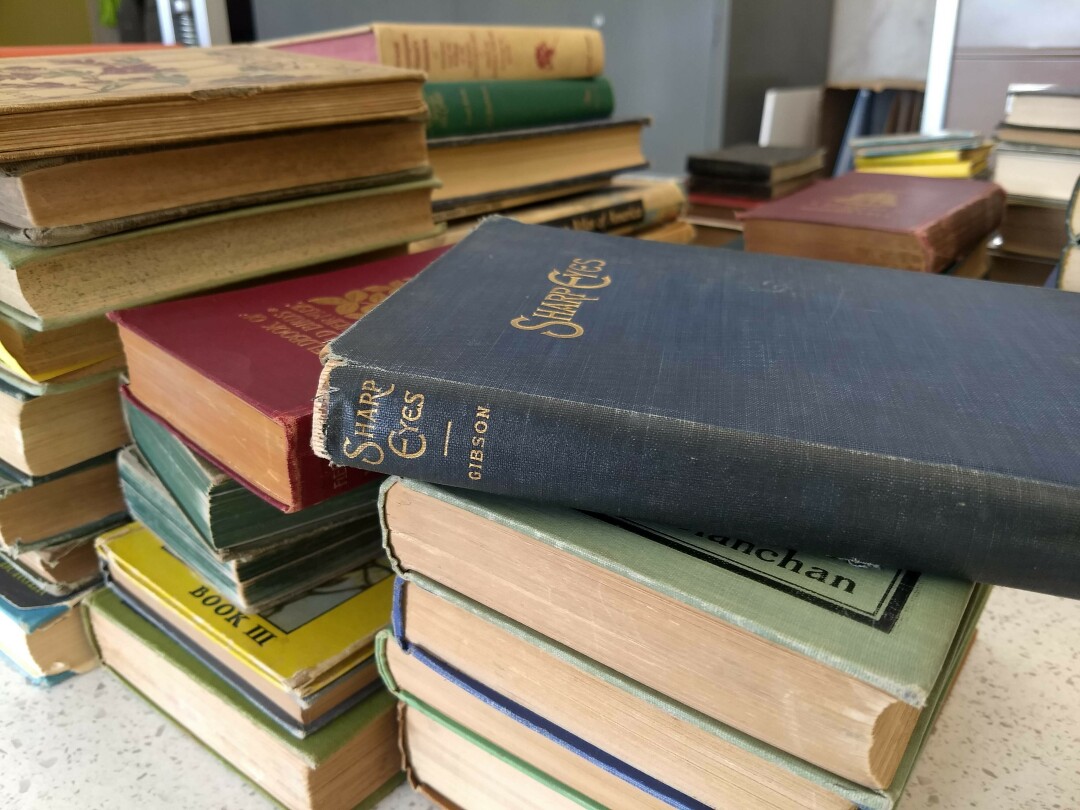

"Sharp Eyes" by William Hamilton Gibson is one of many old books we’ve been delighting over at the Cable Natural History Museum. Photo by Emily Stone.

Winter often brings moments of delight when clean drifts of snow become the canvas for nature’s artwork. If not lost in the tunnel of my thoughts, I might notice the shadows of twigs making purple lace across the white or the detail in a papery seed or frost-lined track.

Sometimes it helps to have a friend along to make their own unique observations.

Earlier today I began digging through folders to find photos of those winter delights. Soon I’ll share them with local artist Janet Moore’s “Wheel of the Year: Four Seasons” class. This virtual class will meet nine times this coming year to create a unique piece of art chronicling the seasons in your own woods.

Just outside my office door, coworkers were exclaiming about delights of a different kind. A generous museum member has given us a few boxes of old books. I expected the nature guides from the 1950s, and big stack of Sigurd Olson’s books, but mixed in with those were cloth-bound covers with shiny gold lettering and copyrights dating back to the 1800s.

I lifted one off the pile, enjoying the texture of the midnight blue cover and the history implied by frayed corners. Sharp Eyes gleamed in gold.

Was this a story about far-seeing raptors? Or hyper-focused wolves?

Inside, the subtitle gave more clues: A Rambler’s Calendar of Fifty-Two Weeks among Insects, Birds, and Flowers.

So this was a book about phenology – the study of when specific events happen in nature from year to year in a specific place. The short chapters and black-and-white illustrations reminded me of my own Natural Connections books.

As I skimmed the introduction, a sentence caught my eye.

[Sharp Eyes is] “a cordial recommendation and invitation to walk the woods and fields with me, and reap the perpetual “harvest of a quiet eye,” which Nature everywhere bestows; to witness with me the strange revelations of this wild bal masque [masquerade ball]; to laugh, to admire, to study, to ponder, to philosophize between the lines – to question, and always to rejoice and give thanks!”

I chuckled a little at the verbose style of the era, but felt a kinship with the author nonetheless. We write in the same genre, and with the same purpose. I took the author up on the invitation, but who were they?

Skimming past a few more rambling pages, I found his signature at the bottom: W. Hamilton Gibson, Washington, Conn., July 10, 1891.

Quick research told me that Gibson’s father’s death forced him into gainful employment as an insurance salesman, but that lasted less than a year before he turned back to writing about and illustrating nature. I can’t say I blame him.

With a glance to the snowdrifts outside my window, I flipped to the last section of the book, where a whimsical version of WINTER endured a blizzard on the page. How would Gibson’s observations in western Connecticut compare to mine?

Gibson illustrated his own books in great detail, including this sketch of the bracts of birch catkins on the snow.

“But both boys and girls may well put aside their sleds for a walk with me this morning,” wrote Gibson. “This snow is good for something else than coasting…” Oh is it now, I chucked, thinking back to how much fun I’d had writing about the natural history of sledding.

“Those who like a good story-book will do well to study the snow, for they may indeed read it like a book. It is a great white page storied with the doings of the little wild folk which few of us ever see.”

I nodded in agreement, thinking of the many photos of mouse and bobcat tracks that now filled my folder for Janet’s class, and the wolf tracks still visible on my driveway.

“They write their autobiography day by day…but they are not responsible for all the singular hieroglyphics to be seen on this great white page. The wind often takes a hand, and after a light, fresh snow-fall plays pretty pranks with the drooping stems of some of the withered grasses.”

Last winter I struggled to find something kind to write about the gray squirrels that attacked my bird feeders, but Gibson had no such prejudices, and wrote,

“On almost any genial day we are sure of him if our eyes are sharp enough, and our manners sufficiently decorous…Let us observe our squirrel carefully. There he goes in graceful bounds across the snow, his sensitive plumy tail in every movement expressive of its homage to the line of beauty.”

After that I had to set the book aside and tackle other projects. But this was a happy moment of connection.

I know I’ll join Mr. Gibson on another walk again soon. This blue-coated man with gold trim will be a friend who will help me make unique – if also longwinded – observations through all four seasons.

Emily Stone is Naturalist/Education Director at the Cable Natural History Museum. Her award-winning second book, Natural Connections: Dreaming of an Elfin Skimmer, is available to purchase at cablemuseum.org/books and at your local independent bookstore, too. For more than 50 years, the Cable Natural History Museum has served to connect you to the Northwoods. Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, and cablemuseum.org to see what we are up to.

| Tweet |