News & Articles

Browse all content by date.

As the first flakes fall, they often don’t reach the ground. In the air spaces below leaves, sticks, and other objects on the forest floor, the Subnivean Zone begins to form. Photos by Emily Stone.

One evening in the 1970s, little Gary Siegwarth learned a lesson. While outside his family’s home in Iowa there had been a big snowstorm, inside there was ice cream – ice cream that had to be shared among five kids.

Wanting to make sure that he got his fair share, young Gary took the cardboard carton out of the freezer, then out of the house, and hid it deep within one of the drifts. When he came back a day later, the sweet treat was just a melty, unappetizing blob.

“I thought it was the perfect hiding place from my siblings, Gary told me, “Turns out the ice cream cache quickly metamorphosized into a subnivean shake…I was surprised. I just never really thought about it.”

Gary had accidentally discovered the magical realm of the Subnivean Zone.

I’ve been wanting to explore that world a little more, too, but instead of burying precious ice cream, I buried thermometers.

The night before our first big snowstorm, I wrapped a few indoor/outdoor temperature sensors in plastic wrap and placed them where I thought snowdrifts would soon form.

One sensor is under the boughs of a hemlock tree. Deer and snowshoe hares are known to seek the cover of evergreens in winter, because those dense needles prevent some warmth from escaping to the stars.

Another sensor is out in the open – just to the side of the planned sledding run – and I made sure to snuggle it in under dry autumn leaves and fern stems.

The third sensor is leaning against the base of an ash tree. This one I expect to become more interesting in the spring, when tree wells expand in the strengthening sun.

The final sensor is dangling about four feet above the ground, in the branches of a dying spruce, in an attempt to shade it from the sun and get the most accurate air temperature possible.

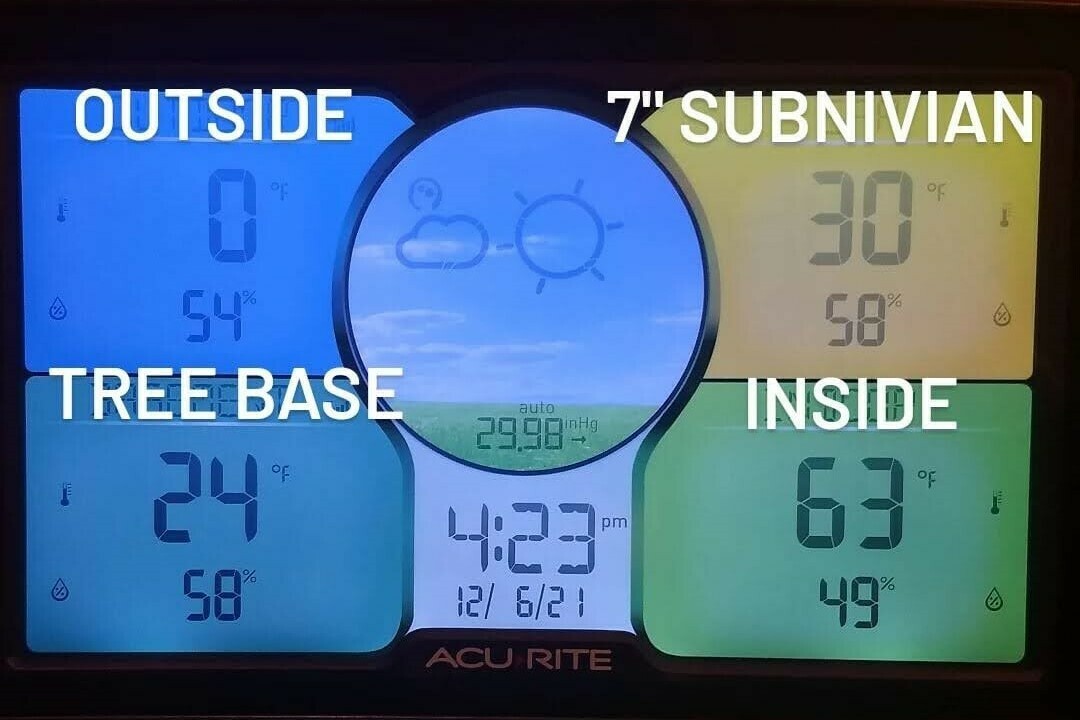

Thermometers in place, I snuggled in, too. By dawn, the sky had shaken down about five inches of dry, fluffy snow. By the end of the day, the total was seven. I watched the digital weather station eagerly, as temperatures from each of the thermometers shifted and changed. I knew that the data would get more interesting as the air temperature dropped.

Sure enough, the evening after the storm, when air temps hit zero in the dying spruce, every other thermometer was significantly warmer, and none more drastically than the one placed in the open, under leaves, with the thickest blanket of snow. Its temperature read 30 degrees.

Even as the air temp sank down to 8 below, the buried thermometer only reached 27.

According to the International Dairy Food Association, the ideal temperature for ice cream storage is zero degrees Fahrenheit and should not rise above 10.

It’s no wonder that young Gary’s ice cream melted! He had placed his stolen treat in the same microclimate as my temperature sensor in the Subnivean Zone.

As winter’s first snowflakes drift through the dark, some land on top of dead plants, fallen leaves, twigs and other detritus of the forest floor. In many places, snow never fully reaches the ground.

In addition, the residual heat of summer still radiates from the earth. This warmth causes the bottommost snowflakes to sublimate – or transition directly to water vapor without becoming liquid first. The damp air then rises through the snowpack and refreezes into a crystal ceiling above spacious (for a mouse) rooms and runs.

In this space, with a blanket of snow to trap the earth’s warmth, and a solid break against the windchill, temperatures hover around freezing. Deeper snow provides even more insulation, and all manner of critters – from mice to martens, bacteria, fungi, spiders, hibernating insects, frozen wood frogs and more – rely on the moderated microclimate.

This winter I’ll be observing the difference in temperature fluctuations both above and beneath the snow.

To Gary’s credit, it didn’t take much thinking for him to figure out what had gone wrong. As a kid in farm country, he’d heard many times that a blanket of snow was better for the alfalfa and protected it from winter kill. He also had plenty of direct experience with the relative warmth of snow forts.

And still, it can take a while for information to sink in. Years later, in junior high, teenage Gary was playing football at a neighbor’s house. They grabbed a snack of ice cream sandwiches out of the freezer and Gary buried his in the snow for safekeeping. As before, the deliciousness melted and oozed away. That was the last time he experimented with ice cream in the Subnivean Zone.

While Gary never admitted guilt to his family in the case of the disappearing ice cream (he thinks he probably got in trouble even while taking the 5th), he still learned something important from these two accidental experiments. And he went on to become a scientist.

I’m not going to put any ice cream at risk this winter, but I am going to watch eagerly as my experiment in the snow plays out. How will deeper drifts and colder air temps impact the Subnivean Zone? I’ll be sure to let you know when I find out!

Emily’s award-winning second book, Natural Connections: Dreaming of an Elfin Skimmer, is now available to purchase at www.cablemuseum.org/books and at your local independent bookstore, too.

For more than 50 years, the Cable Natural History Museum has served to connect you to the Northwoods. The Museum is now open with our exciting Mysteries of the Night exhibit. Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, and cablemuseum.org to see what we are up to.

Even though the surface of the drifts may look smooth and cold, beneath their surface likes a relatively warm and protected habitat known as the Subnivean Zone.

| Tweet |