News & Articles

Browse all content by date.

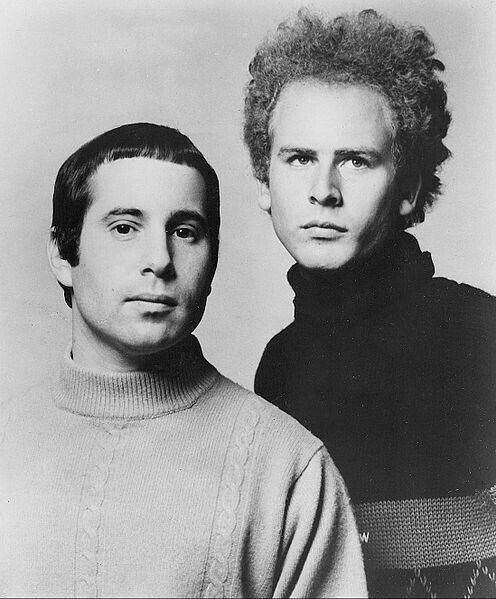

Simon and Garfunkel in 1968

William Carlos William, in his introduction to Ginsberg’s Howl, wrote, “We are blind and live our blind lives out in blindness. Poets are damned but they are not blind, they see with the eyes of the angels.”

These words of a lifelong physician and Pulitzer Prize poet came to mind Oct. 13, the day in 1941 that Paul Simon was born.

While flipping through some of my Simon and Garfunkel and Paul Simon albums, and recalling most of the songs that garnered the duo seven Grammy Awards and Simon, in time, 13, I thought about his legacy as a popular songwriter.

In his 20s, unlike most of his songwriting peers in the ‘60s, Paul Simon’s learning curve as a songwriter flattened out faster than you can say, “Folk rock.” For example, it did not take long for him to learn how to add style, compress content, and use traditional poetic techniques to spice up lyrics that, without such literary flavorings, would be bland.

Within 14 studio and four live albums he has written many songs that I see as game-changing tunes, musical and lyrical compositions that bookmark his personal and our social moments, in signature ways like in a baseball game when a clutch hit or “high-five” fielding play turns around a tight, late-inning game.

“The Boy in the Bubble,” “The Late Great Johnny Ace,” “America,” and “An American Tune” are examples of such songwriting game changers. Why?

In these songs Simon’s use of alliteration, imagery, parallel structure, metaphor and repetition, especially in “The Boy . . .,” cause the lyrics to flash by us the way a savvy base stealer starts sliding into a base almost before the catcher can dig the pitched ball out of his mitt.

About this song, Jeff Jones, WOJB-FM Woodland Community Radio Music Director, observes, “Love the rhythmic play between the accordion (Forere Motloheloa – also co-writer with Simon) and the bass. The mbaqanga “township jive,” the zydeco lilt, the rock ‘n’ roll back-beat - it just propels the song along so joyfully, provides a counterpoint to the serious social justice issues that the lyrics address.”

Most of us can still recall how low our hearts sank the day John Lennon died. However, few of us, let alone those fewer who write to be read, could capture the impact Lennon’s words and music like Simon did when, to pay tribute to Lennon, he balanced the extended metaphor of “Johnny Ace” with a personal narrative that hits home because it breaks hearts beyond the writer’s own.

Regarding “The Late Great Johnny Ace” Jones shares, “The lonely, dissonant melody sends chills up and down my spine. That middle section shifts to the ‘Year of the Beatles, Year of the Rolling Stones,’ with that languid R ‘n’ B shuffle and there’s that minimal winds and strings outro is so good. Of course, Phillip Glass is on the orchestration.”

Written only five years apart, “America” and “An American Tune” each take us on guided word walks that never shuffle behind or race ahead of us. These two songs, by setting and developing their somber tones, take us down distinctly different narrative roads, however, though their focused images, questions, and repeating lines, allow to stand still, look around, and catch our breaths before arriving at places of understanding we did not know we were walking uphill to until, at each song’s conclusion, we feel stopped in our tracks yet still moving.

Of “America” Jones notes, “One of the Simon & Garfunkel songs that’s been etched into our collective souls. Have listened to it hundreds of times. The melodies that Simon weaves with the vocal verses and the instrumental lines are genius. The instrumental fills, modulations, and key changes create a palette of moods from optimism to disenchantment. I close my eyes and see an American story played out in the style of the French New Wave.”

About “An American Tune,” Jones writes, “A hymn of the American experience. And it truly is a hymn, based on a J.S. Bach melody in the sacred work, St. Matthew Passion, the part with ‘O Sacred Head, Now Wounded.’ The melody and harmonies in this carry me like a well-loved hymn might. The bridge comes along with its dream of death and the soul taking flight, incorporating more modern melodies and intervals before it returns to the Baroque theme to close the hymn. Have I mentioned Simon’s genius with melody? Can’t say enough about it.”

Numerous other songs by Paul Simon I consider, in baseball lingo, “Grand Slams” but not “Shots Heard Around the World.” Some of these four-run homer songs include: “The Obvious Child,” “Father and Daughter,” “The Boxer” and “Song About the Moon.”

As in other songs by Simon, “The Obvious Child” weaves a personal narrative voice with psychological subject matter. Also, the songwriter’s wry humor and satirical observations about 20th Century American life, including how we grapple with aging, ring out with “crack of the bat” clarity in the rhetorical question “Why deny the obvious child?” and the apt allusion “The cross is in the ballpark.”

While “Father and Daughter” and “The Boxer” are timeless examples of empathetic songwriting, it is the less widely known “Song About the Moon” that, due to its polished descriptive phrases and understated narration, delivers something fresh and arresting about one of most written about subjects known to man. Throughout this song Simon shows us how he practices what he understands about his art that, “A songwriter’s supreme challenge is being complex and simple at the same time.”

Kari Hedlund, Music Director at KAXE/KBXE Northern Community Radio, has some particular thoughts about Paul Simon’s “Graceland,” “Bridge Over Troubled Water,” “Mrs. Robinson,” and “Sounds of Silence” that I see as similar in their impact on popular music as only a handful of homeruns have been in the big leagues.

Of the song “Graceland” she writes, “I’ve always loved the autobiographical content of this song. Though now more complicated looking through the 2021 lens, the sounds of the African musicians he recruited to play and improvise on the album always draw me in.”

Her take on “Bridge Over Troubled Water” is, “From the first few notes, you can tell that the piano takes the main stage on this song. But when the harmonies come, three and one-half minutes into the song, that’s when the magic really happens for me. Art Garfunkel’s vocals are set low by today’s standards, but add to the intimacy of the recording.”

Although “Mrs. Robinson,” that rivals Cole Porter’s wittiest lyrical writing, was initially only partially completed on the soundtrack album of The Graduate, it was not finished, recorded and released until months after the film became a box office smash.

Says Ms. Hedlund about the song, “The guitar work, bending of the strings and harmonies are all high points, but the funky Bo Diddley back beat with the use of the minor key at points is where it really hits home on this song.”

Paul Simon’s earliest critically acclaimed song, and one that poetically uses a melancholy, conversational approach to counterpunch societal isolation is “Sounds of Silence.”

Concerning its music Ms. Hedlund points out, “ . . . a key piece in the song is the continual harmonies sung on every note. A favorite element of this song for me is the variation in sounds, not just instrument wise, or in the buildup of the song, but in the usage of pianissimo and crescendo you don’t always hear in pop music.”

In his introduction to Howl, William Carlos William said of the book’s author Allen Ginsberg, “He proves to us the spirit of love survives to ennoble our lives if we have the wit, the courage, the faith, and the art to persist.”

We live on a gregarious planet that too often is deaf to our cries of suffering or joy. Too often we are content to lend our ears to nothing beyond the babble of our own echo chambers. Still, we can take solace that we still have ears to listen Paul Simon, who for more than six decades persisted in his art, and, like us readers of The Reader, remains, as he once wrote, “still crazy after all these years.”

| Tweet |