News & Articles

Browse all content by date.

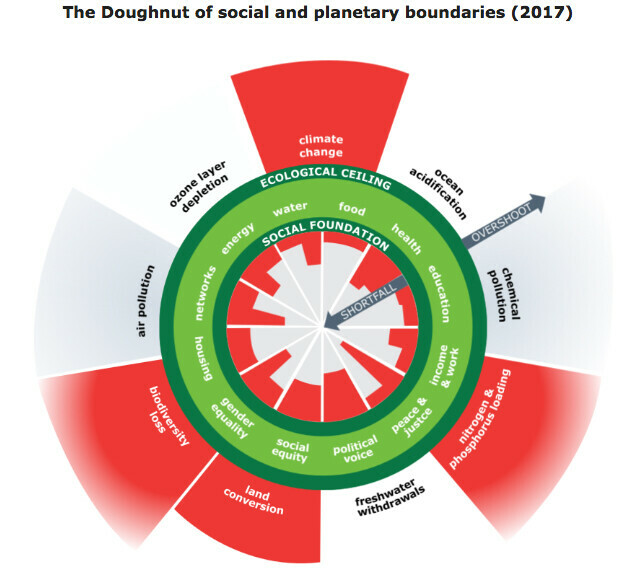

Source: kateraworth.com/doughnut

Source: kateraworth.com/doughnut

In April, 2020, Amsterdam’s city government announced that it would adopt “doughnut economics” in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and the climate crisis. 20 percent of their citizens were unable to cover their basic needs after paying for rent and only about 12 percent of approximately 60,000 online applicants for social housing had been successful. Also, the city’s carbon dioxide emissions were 31 percent above its 1990 level, and imports of building materials, food and consumer products from outside the city were responsible for 62 percent of its total emissions.

Guided by the Doughnut Economics Action Lab (DEAL), Amsterdam would be introducing new infrastructure projects, employment programs and new policies for government contracts. Also, 400 local people and organizations were setting up a network called the Amsterdam Doughnut Coalition to run their own programs at a grassroots level.

Doughnut economics is the brainchild of Kate Raworth, a British economist from Oxford University’s Environmental Change Institute. In her book “Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist,” Raworth presented a theoretical and visual framework for sustainable development. Shaped like a doughnut, this theory connects the concept of social foundations with planetary boundaries. The center hole or inner ring addresses and represents the percentage of the population who lack access to “life’s essentials” - the social foundations - while the outer ring represents the “ecological ceiling” that life and humans depend upon but cannot be overutilized or depleted.

The social foundations for doughnut economics include housing, income and work, food, water, health and education. The ecological ceiling includes climate change, biodiversity loss and air pollution.

In April, 2019, C40, a network of 97 cities that’s focused on climate change, asked Raworth to produce reports on three of its cities - Philadelphia. Portland and Amsterdam. Amsterdam was already exploring a “circular economic strategy” for the city, and wanted to move forward with reducing, reusing and recycling materials across consumer goods, building materials and food. “All of our mayors are working on this question: How do we rebuild our cities post-COVID?” stated Joshua Alpert, the Portland-based director of special projects at C40.

With Amsterdam becoming the first city in the world to adopt this new radical economic theory, with the premise that economic growth shouldn’t be the ultimate measure of success, the city announced that by 2030 it would reduce overall consumption by 20 percent and reduce food waste by 50 percent. Also, starting in 2022, all new urban developments must use sustainable materials as much as possible. And when Amsterdam recognized that thousands of their citizens didn’t have access to computers, the city decided that rather than buy new computers - which were expensive and contribute to the growing problem of e-waste - the city collected old and broken laptops, hired a business to refurbish them and distributed them to 3,500 people.

Also, the textile suppliers, jeans companies and others in the denim supply chain, signed the “Denim Deal,” an agreement to work together to produce three million garments that included 20 percent recycled materials by 2033.

Doughnut economics requires the city’s stakeholders to determine what benchmarks would bring them inside the doughnut; whether it be to set emissions limits or end homelessness. “We are getting very, very clear signals for the earth system, from climate breakdown, from ecological breakdown, that the way we are pursuing growth is destroying the living systems on which we depend,” stated Raworth. For Raworth, doughnut economics focuses on protecting the environment while meeting the citizens’ basic needs.

Copenhagen’s city council decided to follow Amsterdam in June, 2020, along with a number of cities in New Zealand and British Columbia. And then Portland joined the doughnut economics movement. The staff in their Bureau of Planning and Sustainability (BPS) are using concepts from doughnut economics to create strategies for consumption. Their Climate Action Plan calls for the BPS to develop a “sustainable consumption and production strategy” to prioritize local government activities that will support a shift to lower carbon consumption patterns. Also, workgroups of community stakeholders examined where carbon emissions were specifically associated with consumption and production in Portland. They used data to brainstorm interventions in the areas of construction, electronics, food goods and services.

So, how do we bring doughnut economics to Duluth? First, we could set up a small group of community stakeholders - including economists, architects, social workers and teachers - to begin studying and discussing this new theory and its potential applications for Duluth. Then we invite the Doughnut Economics Action Lab to Duluth to help us set up a local lab and begin setting goals for the initiative. We ask the sustainability officer and our city government to introduce the basic theory of doughnut economics, along with some practical applications, in the new climate action plan that is being drafted for the city council. And then we begin a dialogue with various individuals and organizations on where we could introduce and initiate small, grassroots projects around the city that address one or more of the social and ecological elements in the doughnut.

| Tweet |