News & Articles

Browse all content by date.

Jimmy Stewart was a Princeton graduate, a Broadway actor, an Academy Award-winning A-list movie star, a decorated Air Corps bomber pilot in WWII, and he still took time to write doggerel that he recited on the Tonight Show with Johnny Carson. It should not surprise you that a lot of people try their hand at writing poems, with varying degrees of success.

I began this venture by summarizing some of Shakespeare’s works in double dactyl poems. My friend Darcy pointed out another possibility to me, and here is a summary of James Joyce’s “Ulysses” ( or at least, the first chapter):

Follically, Gaelically,

Malachai Mulligan

Hyperborean — gets

Nude with aplomb;

Talking to Dadelus

Inconsequentially

Blaming perverseness for

Killing his mom.

Later in Ulysses, Joyce writes his own poem, but it’s a limerick:

There’s a ponderous pundit MacHugh

Who wears goggles of ebony hue.

As he mostly sees double

To wear them why trouble?

I can’t see the Joe Miller. Can you?

Joe Miller refers to an English actor from the early 1700s. He hung out at a local bar, where his friends knew him as a very serious sort, so they began to ascribe every new joke to him. After his death, several books were published with names like “Joe Miller’s Joke Book,” which contained mostly stale jokes, so bad jokes began to be called Joe Millers.

I know it’s hard to believe, but even limericks have rules. It has mostly to do with meter, or the rhythm of the rhyme. Dactyl words, you may recall, go DUH duh duh. Limericks are based on Anapest meters, which are the opposite of Dactyls: duh duh DUH. The example often given of an anapest poem is “The Night Before Christmas.”

Limericks are described as a form of anapest trimeter, which means three anapests per line: duh duh DUH, duh duh DUH, duh duh DUH. There are three anapests in the first, second and last line, and two anapests in the third and fourth line.

Poems that don’t follow these rules can lead to that “awkward phrasing” I referred to in a former column. If you read the last line of Joyce’s limerick with and without the “the,” you will see that even great writers don’t always follow the rules exactly. I think the rhythm of the poem is better without that extra word.

Gerry, my old colleague and friend, LOVES to write limericks, and he has sent me about half a dozen booklets of them and told me to share. He also loves puns, and he is sometimes willing to screw up the meter for a pun:

An airport worker, Sue Castor,

Helping start a plane for her pastor,

Backed into the prop,

Unable to stop.

Poor Sue, the propellor DISASTER!

This seems to be a favorite theme:

An old sausage maker named Kirk,

One day went completely berserk.

He reached for his binder,

Backed into his grinder.

And got a little behind in his work!

And sometimes I can’t stand it any more, and have to rewrite that “awkward phrasing.”:

There was an old wino named Went

Who took an apartment in Kent.

He had one major trouble,

He always saw double,

So the landlord doubled his rent.

This was the original, so you can compare:

There was an old drunk named Went

Who rented an apartment in Kent.

He had one major flaw

He saw twice what he saw

So the landlord doubled his rent.

The first line could also have been reworded:”There was an old drunkard named Went.” In the second line, a one syllable word is required in place of “rented.” It’s the number of syllables that’s important to maintain the rhythm of the poem.

When my friend Jeanne was visiting family here, I showed her my poem about the kiwi. After she returned to the West Coast, she sent me a poem in return. I thought I had lost it, but I recently came across it while I was going through some old files, so here it is:

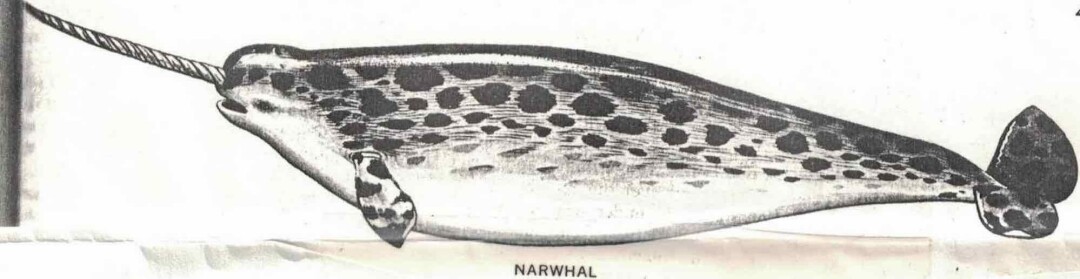

The narwhal achieves at least parity

With the kiwi, a natural rarity.

Its spike on the loose,

Ocean ships it can goose,

With varying degrees of severity.

R.I.P. Jeanne.

| Tweet |