News & Articles

Browse all content by date.

The United States of America is terribly divided. A new president has been elected and almost half the country is angry that this particular man was elected. Plotters plan to take him down before he can assume the presidency.

Sound familiar?

We’re talking 1861 here and the recent election of Republican Abraham Lincoln. As the president-elect was to make his way to Washington for the March inauguration, Allan Pinkerton, founder of the Pinkerton National Detective Agency, learned of a plot to assassinate Lincoln in Baltimore. This obscure episode in American history is known as “the Baltimore Plot.”

Pinkerton took charge of getting the president-elect to Washington, D.C., and averting the assassination plot in Baltimore. The president-elect was to stop in Baltimore for a quick speech before continuing the journey to the capital, however, the speech was canceled and Lincoln – supposedly in disguise – was secreted out of Baltimore. That is the only known fact of the Baltimore Plot, that Lincoln snuck out of the city, much to the chagrin of his detractors who throughout his presidency accused him of cowardice.

What is not known for certain is whether there really was a plot to assassinate Lincoln before he took office.

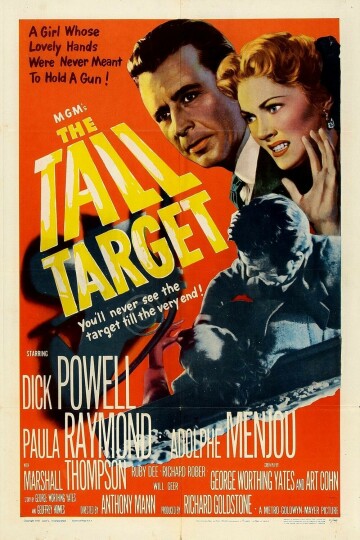

Director Anthony Mann certainly thought there was a plot against Lincoln, and told the story in a very film noirish way in his 1951 feature The Tall Target.

Mann had a string of outstanding films noir to his credit by 1951 – Strangers in the Night (1944), The Great Flamarion and Two O’Clock Courage (both 1945), Strange Impersonation (1946), T-Men and Railroaded (both 1947), He Walked by Night (uncredited as director) and Raw Deal (both 1948) and the 1949 trifecta of Border Incident, Reign of Terror and Follow Me Quietly.

In the 1950s Mann began making a series of noirish westerns starring Jimmy Stewart – Winchester ’73, The Naked Spur, The Man from Laramie, as well as more mainstream fare (The Glenn Miller Story and Strategic Air Command, both starring Stewart).

So, it is not too surprising to come across this 1951 movie by Mann about an assassination plot against newly elected Abraham Lincoln, told with all the shadowy elements and dark motives you expect from film noir.

The film begins with this prologue: “Ninety years ago a lonely traveler boarded the night train from New York to Washington, D.C., and when he reached his destination, his passage had become a forgotten chapter in the history of the United States. This motion picture is a dramatization of that disputed journey.”

Allan Pinkerton is nowhere to be seen in this tale. One-time crooner Dick Powell is the hero saving Lincoln from an assassin’s bullet (in the original plot uncovered by Pinkerton, a group of men was to create a diversion for Lincoln’s security force while Lincoln was to be stabbed to death in a Caesar-like assassination of many blades).

Lincoln did give a speech in Philadelphia on Feb. 22, and was to do the same the next day in Baltimore. Instead, Pinkerton secreted himself, Lincoln and a female operative in a sleeping car. To avoid the possibility of an attempt on his life, Lincoln’s car was uncoupled from the train in Baltimore and hauled by horses to another connection to Washington, D.C.

In the film, a team of horses is employed to pull the entire train through Baltimore because, as one character explains, the women of Baltimore petitioned the city to stop the trains from dirtying their laundry with engine smoke.

Powell plays New York City police officer John Kennedy, who once was assigned to protect Lincoln during two days of campaigning in New York City, and Kennedy said he learned in those two days that Mr. Lincoln was one of the finest human beings he’d ever had the privilege to meet, and because of that, he resigns from the NYC police department when his bosses don’t take the assassination threat seriously.

Any film noir is only as good as its villain, and here the villain is a very amiable Adolphe Menjou, playing Col. Caleb Jeffers, leading “Poughkeepsie’s finest” soldiers to Washington, on the same train as Lincoln.

Going all the way back to his turn as conniving editor Walter Burns in the great newspaper movie The Front Page (1931), I’ve enjoyed Menjou’s performances. However, as a human being, he was a wealthy red-baiting conservative who believed all Democrats were socialists trying to deprive him of his money. He happily testified about the Communist influence in Hollywood during the 1947 hearings held by the House Committee on Un-American Activities (of which Wisconsin Sen. Joseph McCarthy had absolutely nothing to do with, but that story is for another time).

In a closed-door session, Menjou famously said: “Hollywood is one of the main centers of communist activities in America due to the fact that our greatest medium for propaganda – the motion pictures -- is located here. It is the desire of the masters in Moscow to use this medium for their purposes, which is for the overthrow of the American government.”

Interesting, then, that in The Tall Target, Menjou is cast with Will Geer, who plays the much put-upon conductor on the train. In addition to acting, Geer had been a labor organizer and was good friends with Woodie Guthrie. Geer appeared in four movies in 1951, and then due to blacklisting had only three more movie roles throughout the rest of the 1950s (one of which he produced, Salt of the Earth, 1954 – a groundbreaking documentary-style film about a strike that championed both feminism and the labor movement, and that was made exclusively by people who had been blacklisted).

Of course Geer would work almost endlessly in the 1960s and ‘70s, most notably as Grandpa on The Waltons.

I would love to know more about the tension on the set between these two Hollywood polar opposites.

Though set in 1861, The Tall Target looks like a film noir of the period, thanks largely to cinematographer Paul Vogel, whose career dates back to Tod Browning’s 1932 horror classic Freaks. Light and shadow are characters here, as much as the hired actors.

Ever since seeing Powell years ago in one of my very favorite noirs, Murder My Sweet (1944) – the first ever Phillip Marlowe movie, based on Raymond Chandler’s Farewell My Lovely – Powell has been one of my favorite noir heroes, perhaps because he doesn’t look that formidable, but he perseveres. He seems like your average guy thrust into abnormal conditions. (As a sidenote, Murder My Sweet was beautifully directed by Edward Dymtryk, another director who would lose work through blacklisting).

And, so, I was glad to see Powell starring in this odd film noir that I had never heard of before it showed up recently on the Criterion Channel.

In The Tall Target, Powell seems to be one of the few people on the train with a moral compass. The motives of everyone else are suspect. Everyone else seems morally deficient, either by design or by upbringing, which makes me think that if people think we live in an awful time now, what must it have been like in the months leading up to the Civil War? We get, I think, a very good taste of what it must have been like in this movie.

An interesting subplot has a female abolitionist novelist (think of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, she says) interviewing a young slave, sweetly played by a young Ruby Dee. The slave answers questions in front of her southern belle owner, and their two distinct perspectives of their lives and roles are juxtaposed by the nosy lady’s questions.

In the final frames we finally see Lincoln arriving in Washington, passing a Capitol under construction (the almost 9 million pound dome was added 1856-1866), and saying, “Did ever any President come to his inauguration so like a thief in the night?”

| Tweet |