News & Articles

Browse all content by date.

A member of the Church of the Flying Spaghetti Monster, with her religious headgear (a colander) fashioned into a stylish black bowler.

What consititutes a “real” religion? Does it need a god? A devil? Angels? Heaven? Hell?

While the U.S. Supreme Court has wrestled with the idea of what constitutes religion, because of the wide variety of religious views in this country, it has never been able to settle on a definition.

In an 1890 decision (Davis vs. Beason), the court embraced traditional Western religion by ruling that the “term ‘religion’ has reference to one’s view of his relations to his Creator, and to the obligations they impose of reverence for his being and character, and of obedience to his will.”

However, 71 years later the court ruled in a nod to non-Western religions (Torcaso vs. Wakins} that the government cannot make a distinction between “those religions based on a belief in the existence of God as against those religions founded on different beliefs.”

Say an explorer from another world came to Earth and tried to understand religion. Would that independent observer think any one of the world’s many religions is the one true way? Or would she think they all sound insane for putting faith in an unseen “god”?

The Flying Spaghetti Monster: He boiled for your sins.

These questions of what constitutes a true religion is at the heart of the documentary I, Pastafari: A Flying Spaghetti Monster Story, which tells the story of the 21st century religion called Pastafarian, adherents of which believe the Flying Spaghetti Monster is the great creator of all life. They claim to have 10 million members worldwide.

The tenets of the religiion are outlined in the 2006 The Gospel of the Flying Spaghetti Monster, with such laudable goals as ending poverty, curing disease and bringing down the cost of cable.

While it may seem just one more frivolous fake religion, Pastafarians around the world have hired legal counsel to defend the religion in hearings that have allowed adherents to have their drivers license photos shot wearing the religious headgear of the sect, which is a colander or pasta strainer.

We learn, however, that the wearing of colanders is not in the gospel. In fact, in the beginning, Pastafarianism required pirate clothing because they believe all humans are descended from pirates.

But as German Pastafarian Bruder Spaghettus explains, it was an Austrian Pastafarian who introduced the wearing of the colander, and as the Bruder, who continues to wear his pirate cap, says, Germans do not want to follow the lead of another crazy Austrian.

Pastafarian Niko Alm conducts state business in his religious colander.

That Austrian colander wearer, Niko Alm, changed the face of Pastafarianism when he won the right from the Austrian government to wear a colander in his drivers license photo shoot. The authorities, however, said they granted permission not because they recognized the Church of the Flying Spaghetti Monster as a legitimate religion but because Alm’s “religious headgear” did not obscure his face in the photo.

The colanders can be metal or plastic. One follower has attached a black brim to her black colander so that it looks like a bowler hat, and she wears it at a rakish angle reminiscent of the boyos in A Clockwork Orange.

The documentary introduces us to several Pastafarians who take their fight for legal recognition of the religion to court. The Pastafarian legal counsel who represents them says it is impossible to prove that one religion is real and another is fake.

It takes almost three-quarters of this almost hour-long documentary to get to the real point of this noodly religion when we learn that Gospel author Bobby Henderson wrote a letter in 2005 to the Kansas State Board of Education when (shades of the 1925 Scopes Trial!) it made the successful attempt to force public high schools to teach intelligent design along with evolution in science classes (two years later, a new board voted 6-4 to eliminate intelligent design from the curriculum).

The documentary makes the Scopes Trial connection by adding some images from the trial of Tennessee math teacher and athletic coach John Scopes, who agreed to test the state’s ban on teaching evolution.

The American Civil Liberties Union had advertised for someone to challenge the Tennessee law.

Arguing for the state was three-time presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan, and in defense of Scopes was brilliant Chicago defense attorney Clarence Darrow, who eventually called Bryan to the stand and reduced him to a national laughingstock in the major victory for the teaching of evolution.

So, Pastafaria has established itself as a force of good in the world. “He boiled for your sins.”

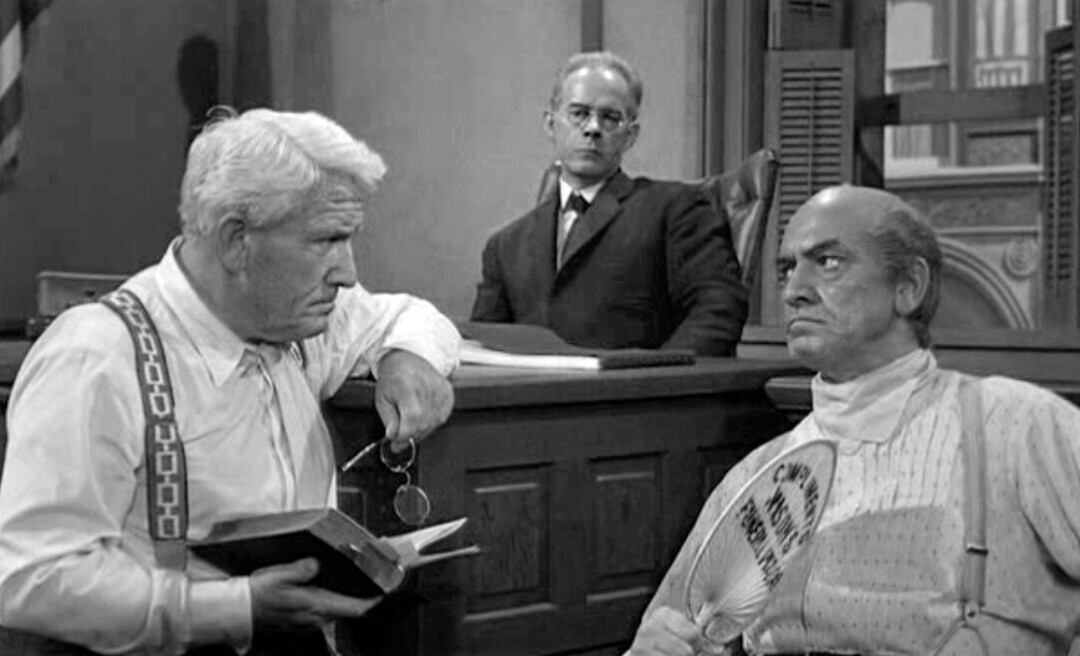

Spencer Tracy (left) as Henry Drummond grills Bible-thumping prosecutor Matthew Brady, played by Fredric March, about the veracity of the Bible. At center, veteran character actor Harry Morgan watches in the role of Judge Merle Coffey.

But the documentary sent me directly to Stanley Kramer’s 1960 movie about the Scopes trial, Inherit the Wind, with Fredric March as the sanctimonious blowhard Matthew Brady (the fictional representation of William Jennings Bryan) and Spencer Tracy as well-known defense lawyer Henry Drummond (Darrow).

Dick York – just a few years away from gaining fame as Elizabeth Montgomery’s husband on Bewitched – played the adventurous science teacher Scopes.

The cast also includes Gene Kelly as influential Baltimore newspaperman E. K. Hornbeck, who is modeled after real Baltimore newspaperman H. L. Mencken, who actually covered the Scopes trial and is credited with dubbing it the “Monkey Trial.” It was, in fact, Mencken and the Baltimore Sun who enlisted Darrow to defend Scopes, and the newspaper paid Darrow’s expenses.

While the movie clearly discusses the question of evolution and creationism, director Kramer was also referencing the suppression of reality that had emerged just a few years before under the dark cloud of McCarthyism.

But you can also take it at face value as a courtroom drama pitting those who believe the Bible to be literal truth and those, who like Henry Drummond, believe Darwinism is as “incontrovertible.”

The best part of this movie is the veracity of the two veteran actors in the leads – March and Tracy are perfect foils as they passionately argue their views in this movie that is not afraid of ideas.

Tracy, especially, delivers some great lines, such as, “Fanaticsm and ignorance is forever busy, and needs feeding.”

When asked what it is he finds holy, Drummond gives this very human answer: “The individual human mind. In a child’s ability to master the multiplication table, there is more holiness than all your shouted hosannas and holy of holies.”

| Tweet |