News & Articles

Browse all content by date.

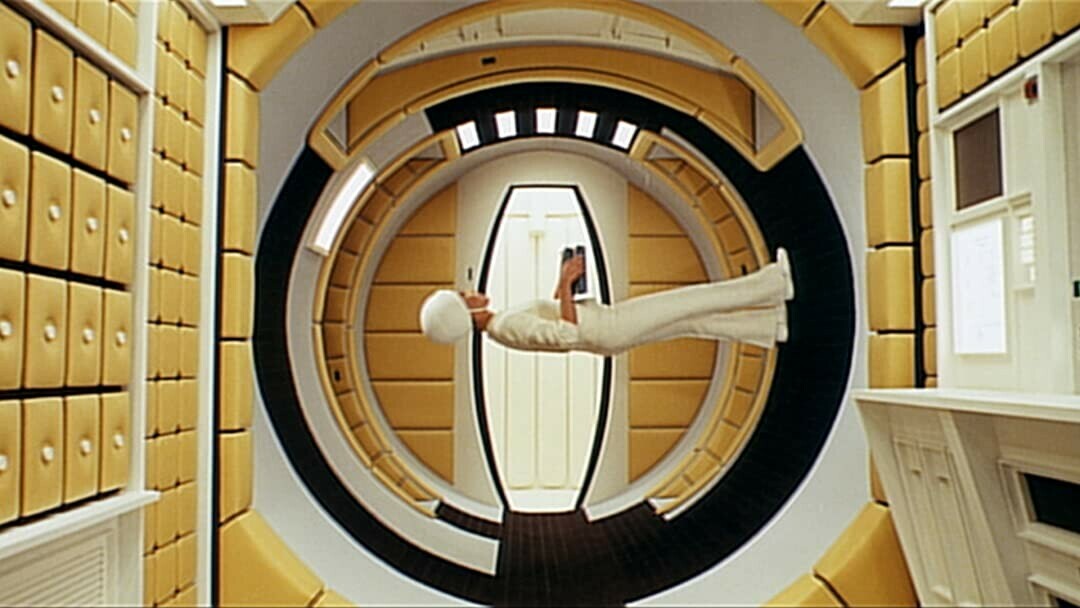

2001: A Space Odyssey

At 9:56 pm CDT on July 20, 1969, Astronaut Neil Armstrong spoke the famous words “That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind” as he became the first human to set foot on the moon.

Or was he really stepping onto a movie-studio set? That’s what the lunar-landing skeptics would have you believe.

I met my first moon-landing denier at a family gathering a dozen years ago when my uncle revealed his disbelief that Americans landed on the moon. He didn’t have any good reasons for his disbelief other than not having much faith in the U.S. government. He piqued my curiosity, and I quickly learned there is a community of disbelievers out there.

One report said that as many as 10 percent of Americans believe the lunar landing was a hoax, and when I read that a whopping 57 percent of Russians think Americans never landed on the moon, I see red, white and blue. It’s a question of patriotism.

The conspiracy theorists who propagate the hoax scenario would turn Apollo 11 astronauts Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins from American heroes of the space race into all-time masters of deceit.

I had my eyes glued to the live images being beamed to television screens worldwide as the first men – Americans, at that – landed on the moon 50 years ago. It generated tremendous national pride and for a brief time brought together two disparate groups: nerds, as represented by the scientists who made the moon landing happen; and jocks, as represented by the pilot/astronauts who piled into those flaming tin cans that we shot into space – the ones who were brave enough to put scientific theory into practice.

Eleven years ago, at the 40th anniversary of the moon landing, I wrote a series of stories about people who have spent considerable energy debunking the theories of those who doubt the moon landing. I’m going to recap some of their thoughts.

Jim Scotti, a researcher at the Lunar and Planetary Lab of the University of Arizona-Tucson, caught my attention with his website, The Moon Landings Were Not Faked. Scotti was almost nine years old when Apollo 11 landed, and he recalled being allowed to stay up late for the moonwalk.

“Watching Apollo had a huge effect on me,” he told me in 2009. “It kindled an interest in science.”

Today Scotti researches near-Earth asteroids at his day job, but the website refuting the myths and legends of the moon landing was purely personal, he told me in 2009:

“I was tired of seeing the hoax theories go unchallenged, and after seeing quite a few web pages make such silly claims, I picked one of them that was fairly representative of the ensemble and built my page around it.

“I do find the hoax claims to be insulting to the history of Apollo and all that it accomplished, especially when I see just how silly and easily debunked their claims are.”

In an August 2008 show, Discovery Channel’s Mythbusters took on the monumental task of debunking some key points of the lunar-landing conspiracy theorists.

“It has actually been on our books since Day One,” Mythbusters Executive Producer Dan Tapster told me in 2009. “It’s arguably the biggest myth out there.”

Finally, Tapster said, the number of people who said they did not believe in the lunar landing was growing to the point where the Mythbusters team said, “This is ridiculous. We have to put this to the test.”

“I’m all up for a good conspiracy,” Tapster said, “but there are elements to the moon-landing conspiracy that actually verge on the offensive.”

In Episode 104, Mythbusters busted several of the top lunar-landing myths promoted by the skeptics, including the waving flag in a vacuum, footprints in a vacuum and supposedly faked photos.

Tapster summed up the Mythbusters mission: “One of the things we’re constantly trying to do on Mythbusters is challenge people not to accept what they have heard, particularly for young people. Challenge what they’ve read, challenge what they’ve heard, to become real thinking people.”

Finally, I reached out to the filmmakers of a 2002 mockumentary called Operation Lune (Dark Side of the Moon), which weaves real and fictional characters in a story of the moon-landing hoax that includes the major detail that it was shot on Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey set. I heard from Luc Martin-Gousset, president of the company that produced the mockumentary, which is available on Amazon Prime.

The film had already been around for seven years when we communicated, so it had to be asked whether he was surprised by how many conspiracy theorists viewed the satirical film as just more ammunition in their anti-moon-landing arsenal and believe that Kubrick – or some Hollywood joker – filmed the landing in a studio.

“The good-bad surprise is that the people who did not get the joke come from any social background,” he said. “People who like to believe in conspiracy theories would tend to take this film at face value. This was a surprise: how much people are fond of conspiracy theories whatever their social background, but generally because they have an agenda – personal, ideological – in mind.”

I begin this week’s exploration of Stanley Kubrick documentaries with that lengthy preface on Operation Lune because it is the largest of many conspiracy theories that have formed around Kubrick’s dense body of work.

If you would like to take a deep dive into the wonder and mystery of Stanley Kubrick, the place to start is Stanley Kubrick: A Life in Pictures, a 2001 (how appropriate!) documentary made by Kubrick’s long-time assistant and brother-in-law Jan Harlan, and narrated by Tom Cruise, who starred in Kubrick’s last film, Eyes Wide Shut.

Harlan introduces us to Kubrick, from precocious urban child to selling his first photograph to Look magazine at the age of 16, and the next year being hired by the magazine, where he developed a much-admired style of photography that told stories, and on to becoming a film director, working at his own material until Kirk Douglas hired the 30-year-old director to take over direction of the epic studio production of Spartacus, an experience which forever ruined studio filmmaking for him and sent him into exile in England, where he made a series of intelligent, challenging, controversial and difficult films on his own terms.

We get some good insight into the making of several movies, while several others are not even mentioned, especially his triumphant early work such as The Killing (a personal favorite of mine, partly because of Tim Carey’s brief appearance as a horse assassin) and the great anti-war drama Paths of Glory.

For a very different and personal look at Kubrick, I would turn next to Filmworker, a 2017 documentary featuring Leon Vitali, who after appearing in Kubrick’s 1975 movie Barry Lyndon, gave up his own career to become Kubrick’s personal assistant for the next quarter century, until Kubrick’s death in 1999.

In the same vein is S is for Stanley – 30 Years Behind the Wheel for Stanley Kubrick, a 2015 Italian documentary featuring Emilio D’Alessandro, who served for three decades as Kubrick’s chauffeur and personal assistant.

The relationship began on a snowy London night while Kubrick was making A Clockwork Orange (1971). Kubrick desperately needed a prop for a key scene – a penis sculpture that is used as a weapon in the film – and minicab driver D’Alessandro delivered it with a promptness in hazardous conditions that impressed the director. So Kubrick hired the man who would become much more than his chauffeur.

The documentary is based on D’Alessandro’s memoir, Stanley Kubrick and Me. He tells some good behind-the-scenes tales, including artistic discussions they had, such as D’Allessandro telling Kubrick that Charles Bronson would have been better than Nicholson in The Shining lead role.

The Shining

Fans of 2001: A Space Odyssey will definitely want to see 2001: The Making of a Myth, a 2001 documentary introduced by director James Cameron. The doc features cast, crew and Kubrick collaborator Arthur C. Clarke, who tells us that when Kubrick approached him to help write the script, the director told Clarke he wanted to make a good science fiction movie.

When Clarke responded that some good ones had already been made, he pointed specifically to the 1936 movie of H. G. Wells’ Things to Come, which Kubrick subsequently watched, dismissed and said he would never take another movie recommendation from Clarke.

One other movie-specific documentary you might want to see is the 2012 documentary Room 237. The title refers to the most haunted room in the Overlook Hotel in The Shining, and the film focuses on interpretations of the movie. For example, why is Danny wearing an Apollo 11 sweater in one scene? Is Kubrick admitting that he actually did shoot the moon landing? Many fanciful ideas are floated, and it’s a fun but not entirely convincing watch.

If you really want to become mired in the conspiracy theories surrounding the films of Stanley Kubrick, there are two that I am aware of, but I’ve seen only one of them, The Mysterious Work of Stanley Kubrick, a 2020 documentary that posits that Kubrick was less a filmmaker than a codemaster, encoding mysteries in his films. Some of the speculations are ridiculous, such as the notion that when Jack Torrance is crazily retyping the sentence “All work and no play…” the first word is a covert reference to Apollo 11. Ugh!

And then on to the Illuminati references in Eyes Wide Shut. Double ugh!

This documentary quotes from the other Kubrick conspiracy film available, Kubrick’s Odyssey: Secrets Hidden in the Films of Stanley Kubrick, which I didn’t watch because by then I was full to the brim with conspiracy theories embedded in Kubrick films.

Was Kubrick making fun of the faked moon landing theories by dressing Danny Torrance in an Apollo 11 sweater?

Frankly, I don’t give a damn. Can I just watch the movies for their own visceral impact?

| Tweet |