News & Articles

Browse all content by date.

Hot damn! It’s the Soggy Mountain Boys! It took a couple of Minnesotans to reinvigorate bluegrass music for the new millennium.

Recently I had the onerous task of letting some family and friends know how disorganized I am by requesting that, yes, once again I need your addresses. When the addresses were compiled, I sat down with a big stack of Christmas cards and planned to get it all done at once, using the leftover Halloween stamps instead of Xmas ones.

To get in the mood, I asked Alexa to play some Christmas music, and then, inexplicably, I added the word “bluegrass.”

Alexa responded with a Prime Video offering called Country Bluegrass Christmas, a 48-minute video celebrating Christmas decorations as the visuals with a soundtrack of music by unnamed bluegrass artists.

That led me down two rabbit holes – trying to find out who the musicians are on Country Bluegrass Christmas, and what else does Prime Video offer in the way of bluegrass?

Turns out there is a rich library of bluegrass music and documentaries available. I took a deep dive into them, and finished with one of my very favorite movies, a movie made by Minnesotans and that accidentally reinvigorated the bluegrass industry at the turn of the century.

Country Bluegrass Christmas is a mixture of familiar carols that have been given the bluegrass treatment, along with some southern gothic-style Christmas renderings in the bluegrass style.

Perhaps I missed them, but I did not see any credits, so I went searching online to find out more, but I only learned that director Joseph V. Micallef has produced several similarly themed videos and might also be a journalist who covers booze.

So, if you’re not too curious and need some background bluegrass Christmas music, this is it.

When next I asked Alex to show me what Amazon has in the way of bluegrass, something popped up that I just had to see because it was a live concert of two musical entities that I never knew got together.

It’s called Leon Russell and New Grass Revival, which documents – with plenty of unnecessary goofy psychedelic video editing – a 1980 concert with the two.

The concert opens with Leon at his piano, singing and playing “Somewhere Over the Rainbow.”

Then the members of New Grass Revival and begin a set of smoking music.

At first, the idea of Leon Russell and this new grass bluegrassers did not gel in my mind. But it all made sense immediately. Of course Leon can sing bluegrass. He has a naturally countrified voice that fit right in with John Cowan and Sam Bush, the two vocalists of New Grass Revival.

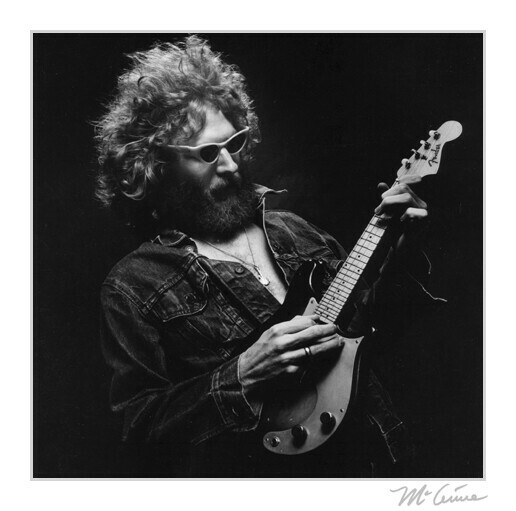

Sam Bush

Sam Bush

But is it bluegrass? That was always the question about New Grass Revival, which began in the early 1970s by performing country, blues, pop and jazz tunes with bluegrass instrumentation, and singlehandedly creating the genre of New Grass.

As a fan of both musical entities, I was excited to see them together. The music obviously inspired Leon to experiment with screaming on some songs. He’s great at it! His piano also fits in nicely with NGR, which at this time was nearing the end of its first decade with Sam Bush (mandolin/vocals), Curtis Burch (guitar), John Cowan (bass/vocals) and Courtney Johnson (banjo – the year after the NGR tour with Leon Russell, Bela Fleck took over banjo duties).

This is a must-see for both Leon Russell and New Grass fans. I dare you to try and sit still during some of this, especially the rip-roaring version of “Jambalaya” or their deconstruction of “Jumpin’ Jack Flash.”

There seemed only one place to go after that, to a documentary about “the father of New Grass” – Revival: The Sam Bush Story (2015).

At the end of this documentary, you will realize that Sam Bush is a musician’s musician.

In some vintage concert footage and more recent footage made just for this documentary, Bush comes across as a rocker as you see him attack his mandolin.

Something that never really occurred to me happens in this documentary – there are people in this world who do not know Sam Bush or his music. How can that be possible when, as you hear from other well-known musicians in this documentary, he is one of the greatest musicians who ever lived, according to Allison Krauss.

We learn that Bush was motivated to play mandolin when he saw a very young Ricky Skaggs playing the mandolin on a TV show with Flatt & Scruggs.

But in the beginning, people didn;t know how to take this group of hippies who played rock ‘n’ roll with bluegrass instrumentation.

Mandolinist Chris Thile says in the documentary that bluegrass is made up of too many people fearful that diversions from tradition will kill the music, but as he and others point out, the roots are too strong, and it can take people exploring it in new directions.

Bill Monroe

Bill Monroe

Bush tells the story of he and his father going to the Ryman Auditorium to see Bill Monroe and the Bluegrass Boys, and being blown away by the blues notes and other things Monroe did on his mandolin.

He also tells a story of his dad being friends with Roy Acuff, who at the time was sort of the king of country music and a Grand Ole Opry stalwart. At the time, Bush was a fiddle player, and after jamming in Acuff’s dressing room, Acuff invited the teenage Bush to play on stage. Shortly after that, he offered the 18-year-old high school student a job in his touring band.

Bush turned down the job offer. “If I was going to play music, that wasn’t the music I wanted to play,” he said.

Would new grass have been born had Bush taken that other path?

New Grass Revival was born in 1971. Bush mentions that as they were touring, they were particularly taken with two albums released in 1971 – John Hartford’s Aereo-Plane and Leon Russell and the Shelter People.

This leads to the story of the TWO YEARS that Leon Russell and New Grass Revival were together. How is this the first time I'm hearing of this lengthy and fruitful musical relationship?

Leon first showed his country roots in 1973 with the release of Hank Wilson’s Back.

Bush said when Russell was about to make another country record in the late 1970s, he needed a band. They played on the record and then were hired to tour with him from 1979 to 1981 when Bush said “we just wore ourselves out.”

We get all sorts of glimpses into the esteem with which Bush is held by his fellow musicians, and they are especially amazed by his rhythm, to which, they say, you can keep time. He explains that the unique slurred chop you hear in his mandolin playing was stolen after listening to Bob Marley play his guitar with similar slurred chops.

When New Grass Revival reformed in 1982, it was with new banjo player Bela Fleck.

In the late 1980s, Fleck left to form his Flecktones, and in 1989, New Grass Revival called it quits.

Watching this documentary and getting a sense of the power of their music, with John Cowan’s vocals and bush’s instrumental sensibilities, it is a pleasure to behold. Wish I could have seen them with Mr. Russell.

The old question of whether new grass is legitimate seems silly when hearing Bush and his colleagues play.

This is a great documentary.

Time to pay respect to tradition with Bill Monroe: Father of Bluegrass Music (1993).

The documentary begins with Bill walking onto an old wooden porch, taking a seat on a wooden swing, opens a small suitcase he had been carrying and pulls out his mandolin, he begins to strum on it as the credits roll.

We learn that the man who brought the mandolin forward in a whole new genre began playing the instrument in his musical family because he was the youngest and the others had picked all the other instruments.

This movie features some great playing from Bill and his fellow travelers. But we also learn that he started out in the music business in a traveling square dance show. He exhibits his technique several times, and we also get to see Emmylou Harris buck dancing with Monroe. We also get to see and hear Monroe with Dolly Parton, Ricky Skaggs, Marty Stuart, Lester Flatt & Earl Scruggs, John Hartford and even Paul McCartney, who is connected, the documentary explains, by the lineage of the vocal harmonies The Beatles employed. The trail eventually leads back to bluegrass.

Monroe was 82 when this docu-mentary was made, and only three years away from his death in 1996. I got the sense that was a dour man with not a lot of humor. Perhaps that’s just due to the age he was when this was made, but some of the stories told seem to back that up, such as a tale Ricky Skaggs tells of performing a song when Monroe was in town and not being received with much enthusiasm by his musical hero.

But, ultimately, it’s about the music, and this is a fun excursion through the short history of bluegrass, as well as a look at its long roots.

Well, by now, I was ready for something a little different. Guess what else popped up when I asked Alexa to find me some bluegrass – O Brother, Where Art Thou.

The Coen brothers’ retelling of Ulysses’ tale might be my favorite comedy. There are things in it that make me laugh out loud every time. George Clooney is at his finest as the Dapper-Dan-using protagonist. I also love the titular movie in-joke. The title is the name of the movie Joel McCrea’s director character wanted to make in Preston Sturges’ Sullivan’s Travels.

Most importantly for the Coens’ 2000 release is what it did for the bluegrass music industry. Because the movie featured “old-timey” music and the plot hinged on the ultimate success of a musical group called the Soggy Bottom Boys, T-Bone Burnett’s soundtrack reinvigorated bluegrass music.

The soundtrack album won Grammys and many best of awards.

I recall interviewing musicians back then – people such as Sam Bush and guitarist Jerry Douglas, a member of Allison Krauss’s band, which played on the O Brother soundtrack – and their gratefulness for the spotlight on their “old-timey” music.

One scene in particular emphasizes the importance of music. The Soggy Mountain Boys are performing for an audience, not knowing they have a major hit on their hands until the first notes of that song are played and the audience immediately reacts: “Hot damn! It’s the Soggy Mountain Boys!”

The camera focuses on Clooney’s character. He’s puzzled by the reaction. Focused on the many trials and tribulations he and his mates have been through, he doesn’t know the Soggy Mountain Boys have a regional hit record. But when he does realize it, and belts out the first words of “I Am a Man of Constant Sorrow,” my heart goes into my throat.

| Tweet |