News & Articles

Browse all content by date.

It was Carol Burnett who said, “Giving birth is like taking your lower lip and forcing it over your head.” Expectant fathers, of course, can’t relate to this level of pain until they get a sliver under a fingernail.

The average baby is about 5 percent of its mother’s weight, so a 120 lb. woman would tend to have a 6 lb. baby. Imagine, if you will then, how it is to be a little brown Kiwi. That New Zealand native lays an egg that is 20 percent of its body weight. Any wonder that the male does all the incubating; the female is too worn out to balance on the egg.

I first became aware of this problem from an article in “Science News,” which remarked that the Kiwi egg was “subject to hairline cracks.” I had just reached my 40s and was being subjected to hairline cracks of my own, so I could sympathize. Accordingly, I wrote the following Kiwi tribute in the form of a couple of limericks:

A Ratite bird may be viewed as absurd,

But none so much as the Kiwi.

Her egg is immense

In an absolute sense,

While she is a relative peewee.

So say a kind word for the Kiwi bird

Though her habits may seem a bit alien.

By the time she makes room

for the fruit of her womb,

Her bottom is tatterdemalion.

The word “Ratite” suggests a connection to rodents, but I assure you it refers to a family of birds, primarily large and flightless birds. They are native to the Southern Hemisphere mostly, so are not a common sight in this country, although my daughter once woke up to find an Emu grazing in her front yard.

Her neighbor, who owned the bird, offered to let her keep it, but she didn’t even enjoy feeding chickens, so he had to put it in his truck. The Emu, taking umbrage with something the farmer said, attacked him on the way home. There is no record of what was said, but the Emu, being Australian, may have misconstrued a fairly normal French-based American saying. Or not.

The next poem, although ostensibly written as a tribute to the Kiwi, is actually a punning tribute to the major ratite species (excluding the Elephant Bird, whose name speaks for itself).

OWED TO THE KIWI

The little brown Kiwi is held aloof

By envious feathered society,

Who say her magnificent egg is proof

Of tasteless impropriety.

A lesser bird would throw in the towel

And turn a non-producer,

But to the Kiwi, cries of “fowl”

Serve only to Emus her.

Though high-flown kinfolk treat her cruel,

The Kiwi is Moa regal

Than that sanctimonious flying fool —

Jonathan Livingston Seagull.

Whether ostrichized by families

Of the avian persuasion

Or threatened by Sword of Damocles,

She’ll Rheas to the occasion.

The Queen of Birds, there is no doubt!

Should any try to top her,

She’ll Cassowary look about,

And drop another whopper.

I suppose you have to be a person of a certain age to get the Jonathan Livingston Seagull reference, although a fourth and totally unnecessary part was published in 2014. The original book sold over a million copies in the ‘70s, and Roger Ebert said it “was so banal that it had to be sold to adults,” implying that kids would gag on it.

The Kiwi has nostrils at the end of its long beak, and its sense of smell is second only to that of a condor, which can smell a rotting carcass from 10,000 feet up. Researchers speculate that the Kiwi was originally the size of a Cassowary, but over time, Mother Nature shrank its body, while the egg stayed the same size. I think it’s reasonable to conclude from this that Mother Nature is a complete ass, even when she’s not talking about margarine.

Twin Ports Review of Books

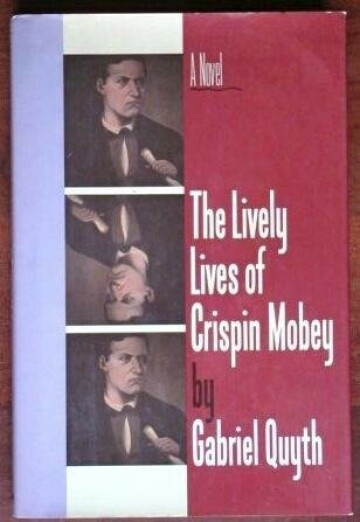

The Lively Lives of Crispin Mobey

By Gabriel Quyth

This book is written as a series of letters either from or about a well-meaning and very naive missionary of the Southern Primitive Protestant Church (SoPrim) of Abysmuth, Mississippi. The first chapter, “Sooner or Later or Never Never,” was published as a short story by Gary Jennings, the author’s real name, which I encountered in a collection called “Best of Fantasy and Science Fiction, 20th Edition,” published in 1974, and concerns Crispin’s attempts to convert an aboriginal tribe in Australia. He is given both good and bad information on what he is getting into, unfortunately most often accepting the bad.

It is a hilarious story and I laughed a lot, but I was also puzzled, because it involves neither science nor the supernatural nor imaginary creatures. As much as I liked it, I didn’t see what recommended it to that particular magazine. From other sources, I learned that the author and the editor of F&SF were drinking buddies, which makes the connection much clearer. I discovered that several of these stories appeared in later F&SF magazines, and then had been collected in the book under the pseudonym of Gabriel Quyth. I found a copy online.

It begins with the following poem:

If I were a cassowary

On the plains of Timbuctoo,

I would eat a missionary,

Skin and bones and hymnbook too.

- Samuel Wilberforce

Bishop of Oxford, 1844-1868

The author of the poem appears to be a clergyman who was well aware of the effectiveness of sending missionaries to attempt to convert primitive people. Michael Palin’s movie “The Missionary” (1982) had a similar theme. I enjoyed that movie a lot, too, and Amazon has it on DVD. They want over $20 for it, and I’m not sure I enjoyed it quite that much. I have seen other movies that cracked me up the first time, but were not as funny the next time I saw it, because there were no surprises left. Besides, as soon as I bought it, Netflix would pick it up.

Gary Jennings (1928-1999),was a respected writer of historical novels. He was one of the few reporters to have won a Bronze Star during the Korean War. He also received a citation from South Korea for his work with war orphans.

In 1957, I was in an Army training company in Texas. One of my fellow students got word that his father had died at home in New York. He went to the Red Cross to see if they could help him get home. They told him they wouldn’t give him anything, because he would feel bad when he couldn’t pay them back. Some 260 other students, mostly making $68 per month minus deductions, took up a collection and got enough money together so he could fly home for his father’s funeral. I always thought that since the Red Cross workers were Southerners and the student was Black, this was pure racism at work.

Gary Jennings had spent time in a Korean war zone, so he was well aware of how the Red Cross operated there and he wasn’t impressed with their operation. He obviously felt that they were good at publicity but bad at providing services and he takes a few potshots at them.

Besides the Red Cross, Jennings hated the hypocrisy he observed from Bible Belt Christians and flag-waving “patriots” from every corner of the country. The humor in this book is satire with that hypocrisy as the target.

Crispin is sent to Oblivia, a small, guano (not suited for growing bananas) Republic in South America to pose as a “neutral” observer. The only export the country has is buzzard guano, and they have more than enough of that, but left-wing and right-wing factions are fighting over who to sell it to, USSR or USA.

While mercy ships from those two countries are trying to ram each other in the harbor, Crispin takes control of the Oblivian Air Force (one used barrage balloon from WWI). Before he leaves, he manages to change the war from political to religious.

He is sent to a KKK and NRA-loving SoPrim member who has built up a little fiefdom in the midst of Cajun country. The man actually wanted mercenaries, not missionaries, as he’d like to kill off the Cajuns, whom he says never shot a Yankee in the War or hung a Black man. His daughter, Cloaca, can’t find a Protestant man, so she’s taking what she can get where she can get it, and he runs afoul of a voodoo woman just before Crispin leaves.

We hear of shows like Praise the Loot and Gimmie Swaggert, but Jim and Tammy Faye are undisguised. Sent to a major Christian conference in New York City, Jerry Falwell is ensconced at the Waldorf Towers while Crispin is booked into a fleabag hotel where the Gideon Bible is a paperback. He gets lost in the subway system and ends up getting a tour of Hell, where he learns that whether Satan resides in Heaven or Hell is all a matter of perspective. Everything looks like Hell to him now, so he goes to the psychiatrists office, and then to Bellevue.The final chapters finally get into the realm of science fiction/fantasy, and the last chapter finds him on a spaceship to Heaven.

I found a whole page of good reviews for this book, giving it from 3 to 5 stars. On one site, I found a review that called it a “labored satire.” I have to agree with that critic. Satire has to be subtle to be effective; a statement is made which almost sounds like a compliment, but really isn’t. Too much of the humor in this book is heavyhanded, a result, I think, of Jennings hating these things too much to waste time being subtle.

On the whole, I was disappointed by the book. There were certainly funny passages in every chapter, but the subsequent chapters did not live up to the promise of the first chapter. I wonder if I would feel the same if I had started with the second chapter and saved the first for last.

| Tweet |