News & Articles

Browse all content by date.

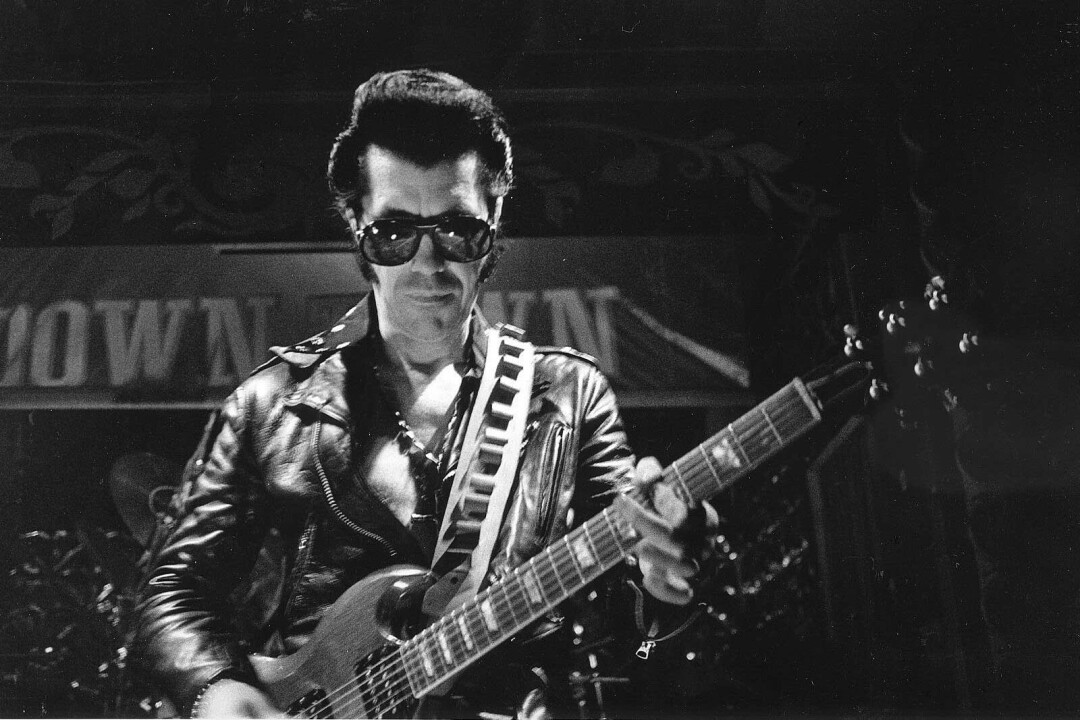

Link Wray

You know that great opening scene in Guardians of the Galaxy where Chris Pratt struts and abuses alien life forms through the film’s credits to Redbone’s “Come and Get Your Love”? The best thing about it? Who doesn’t want to strut when they hear that song with the magically rubbery sitar and bass lines?

Redbone, of course, is included in the movie "Rumble: The Indians Who Rocked the World." Their segment includes a great clip from the 1970s late night music show Midnight Special, in which they perform the long version of “Come and Get Your Love” in native garb, starting the song with ancient tribal chant and dance.

There are so many surprising and uplifting moments throughout this 2017 documentary about Native American influence in the modern music scene – from jazz to folk and blues and pop and hard rock.

First we are introduced to Link Wray, the author of the visceral guitar sound and song for which the film is named. Wray, part Shawnee, grew up in a poor family in North Carolina where one of his relatives said, because of the influence of the Klan at that time, “You didn’t go around telling everybody you were Native American.”

Fellow musicians interviewed for the documentary describe Wray – because of his 1957 song “Rumble” – as the inventor of the power chord.

We are told Wray invented the sound at a hop in 1957 when some of the kids in the audience asked him and the band to play a “stroll.” Instead, Wray came up with a rumble.

The song made it to the radio in 1958. Musician Taj Mahal recalls hearing the song come over his radio one night. “Here comes this sound that makes you levitate out of bed four feet,” he said. “What is he doing? There is no sound like that nowhere on the air.”

And at the University of Michigan, an underclassman named James Osterberg heard “Rumble” over the airwaves on campus, and soon dropped out of college to become Iggy Pop. “’Rumble’ had the power to push me over the edge. It did help me say, fuck it, I’m going to be a musician.”

“The sound of his guitar embodied all my aspirations. It was the sound of freedom,” said MC5 guitarist Wayne Kramer, who added that if any modern guitarist says they were not influenced by Link Wray, they are lying.

“His influence was so immense. Every musician in the world loves Link Wray,” said Dan Auerbach of the Black Keys. “I don’t know why the rest of the world hasn’t figured that out.”

“It changed everything,” said Robbie Robertson, a Mohawk. “‘Rumble’ made an indelible mark on the whole evolution of where rock ‘n’ roll was going to go. And then I found out that he was an Indian.”

And that’s just the first 13 minutes of the movie. From there we go from traditional music of southeast indigenous people forward through time, and we learn of laws that prevented indigenous people from performing their music and the outlawing of drums.

“They went after every part of our culture, so of course they’re going to go after our music because it’s an integral part of our culture. They were songs of the old way,” said John Trudell, for whom the movie is dedicated. “It was genocide and they wanted to erase every cultural perception of reality we have.”

Then we take a trip to New Orleans, where the mix of Native Americans and African Americans is so much a part of the culture and musical gumbo. The case is made for Native American music serving as “pre-blues” or the roots of what would become blues music.

We learn of Mississippi Delta blues musician Charliy Patton, a Choctaw, much admired by musicians such as Keith Richards and Bob Dylan, and considered by many to be the “grandfather” of Delta blues. Several musicians note that Patton played his guitar like a drum, and he had to because drums were illegal for Indians to own.

Native American musician Pura Fe, while listening to Patton’s music, says, “It connects me right back to where I come from. I can hear all those old traditional songs. Do you hear it? That’s Indian music, with a guitar. That’s where it went. That’s where the traditional music went.”

We also hear from and about jazz singer Mildred Bailey, who is credited with sending jazz vocals into a new direction by using sliding vocal effects of her Coeur d’Alene background (she was also the first female band singer and the first female to have a radio show); Buffy Sainte-Marie and Peter LaFarge making their way at an important time in the folk scene; Jimi Hendrix being proud of his part Cherokee heritage; Robbie Robertson, a Mohawk, of The Band and Bob Dylan’s electric conversion; Jesse Ed Davis, a Kiowa guitarist who was much in demand with the British rock aristocracy after playing with Taj Mahal (that’s his bright, one-take guitar lead on Jackson Brown’s “Doctor, My Eyes”); on to Redbone, Apache guitarist Steve Salas who played with, among others, George Clinton and Rod Stewart; and Pueblo/Apache heavy metal drummer Randy Castillo (Black Sabbath).

Rumble, released in 2017 and directed by Catherine Bainbridge, is a must-see for any music fan.

| Tweet |