News & Articles

Browse all content by date.

I like trees. As a kid coming north from Illinois in the family car I endured hours of fields, cows, and corn were slowly, slowly replaced by forest. Modern interstates largely erase that transition by creating an endlessly boring field broken by repetitious exits to another fuel-food stop at an off ramp to an invisible town you’re lucky to find if you try. If I was bored as a child on the long drive north it’s no better now traveling the monotony of industrial size manufactured roadway. When driving along roads made of end to end football fields the real landscape is kept at arm’s length in an environment hostile to trees. There may be a natural world, but it’s to be found only beyond the freeway fringe. I personally think a being needs some adjustment time to adjust from field to forest, but what I think doesn’t matter in a conveyor belt system. In the plush upholstered backseat of a car the appearance of trees outside the window was the happiest news. Trees meant we were getting nearer our destination where fishing, homemade sandwiches wrapped in wax paper at noon, and nights that brought the light scent of smoke from the leaky wood stove adding cozy comfort to the enclosing forested darkness outside the cabin. I knew how to get by on city streets. I could endure hour on hour of fields. But the appearance of trees was more than wood and timber. Trees meant a different way to be and feel alive. I was in most ways dopey as any other ten year old, but I knew a good thing when I saw it. Weedy quick growing balsams made fragrant roofs for a shambling lean to. Without trees I’d be in just another vacant lot or pasture.

I suspect many of us northlanders take our trees too much for granted same as we are so casual about America’s most important poet (and composer) coming from the west end of the Iron Range. That would be Mr. Zimmerman who continues aglow, unlike Rimbaud who flared to bright and then his light went out. Along with taking our trees for obvious goes typical dismissal of what trees have to say about land and life. Red pine, aspen, maple and all the others aren’t simply diverse. Each has specific and individual preferences for soil and amount of water. Red pine doesn’t thrive in bogs. Trees are specialists. When we see slopes covered in autumn red or bright yellows we know certain trees are shouting to the sky “Our kind likes it here! This suits us.” Tree types are picky, too, about their neighbors or their neighbors are picky about them. Either way some flora like one another’s company same as grouse prefer some buds over others. These are like minded communities. In my experience plants make group decisions. Having planted thousands of brown eyes (full name Rudbeckia hirta often seen wild in ditches) only to have none survive I got the clear message “We aren’t living here.” It was an argument the plants were going to and did win.

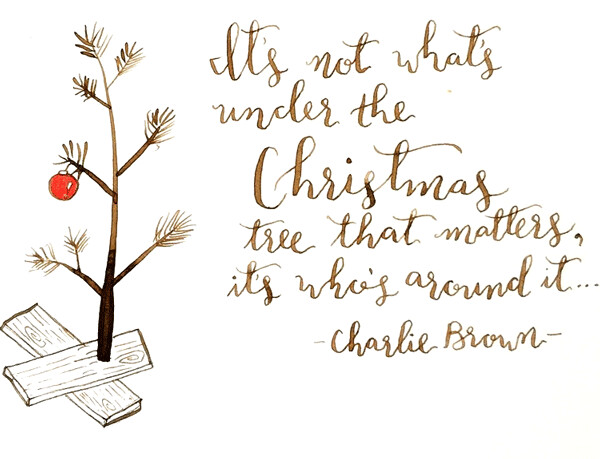

Round about I’m getting to Christmas trees. I could bemoan the waste of good trees, but I won’t. Seems to me the value (overlooked as it might be) of bringing a tree indoors with us is a good reminder. In my teens I took over the seasonal tree getting task. It got me out of the house and allowed me to make an important decision. Mother liked spruce, but she never got one when I did the cutting. I’d pick balsam fir because, in my eyes, they are an ordinary and humble tree. It seemed most fitting to take a lesser species to, as a Brit might say it, put in pride of place. A real balsam in the house smells good, too. In times past Boy Scouts harvested trees along powerlines and right-of-ways to earn money for summer camp. (Think about that in today’s climate of fear, but we all returned home with as many digits as when we left.) A real tree was a symbol and a reminder of the central role of nature.

The reminder was short lived, but not inappropriate and not remembered later without heartfelt appreciation. For practical reasons I now use an artificial tree (not one of those shiny aluminum ones under rotating colored lights my parents tried before we all agreed the result lacked something that made even an artificial pine a better choice). The tree is a symbol. Onto it I place a set of bubble lights from earlier trees and a few fragile glass ornaments that go back to a Polish grandmother I never met. The tree is a reminder of nature, of people, of shared traditions. I’m not so cynical to look on that and see only waste of resources and a cause for complaint.

What’s under the tree is, I think, as much about what we put into the tree and its season as it is about anything else. I had a holiday tradition with my father (born on Christmas Eve) of trying to find one gift he’d possibly use and the other he’d shake his head at. My gifts were a form of game played with my father, who gamely went along with his son’s foolishness. Under the tree and under the gifts was a father to son bond of give and take. I often resented his chiding. He didn’t understand my often aimless restlessness. He wondered would I ever settle down while I wondered the same but without telling anyone. As another of its symbolic forms the holiday tree was also a shelter. Under its branches all things human might be found. There was greed for a bigger gift or dumbfoundment at what an aunt thought a sixteen year old would wear. The good and the ill of people all fit under the tree. Did I always know which was which? Was I always prepared for the moment of surprise when the previously unseen would burst from cover like a grouse jumping noisily into flight?

A tree with nothing under it isn’t sad if I remember giving will usually last longer than getting.

| Tweet |