News & Articles

Browse all content by date.

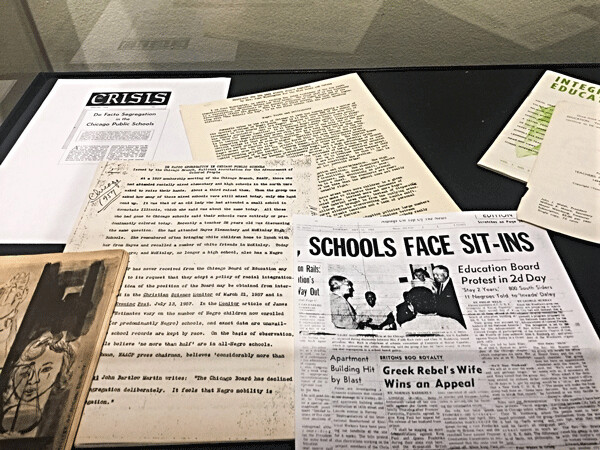

There are still two weeks left to see the current exhibition in the George Morrison Gallery at the Duluth Art Institute titled Jean: The Inspiration Behind the Birkenstein Movement. The handout for this show begins with this description of the artist: Jean Birkenstein Washington (1926-2003) — or simply Jean, as she was called by all who knew her, including her children — was an artist, a teacher and a leader of the Civil Rights Movement in 1950s and 1960s Chicago. Her home served as a safe house and community center for rival gangs, the Vice Lords and Cobras, whose members were free to express themselves through art. Her work emphasized her belief that everything – human, animal or mineral – has its inherent self-worth, leading Jet magazine writer Alex Poinsett to describe her as “an artist with a profound respect for human dignity.”

Jean Birkenstein’s life passions also became the subjects of her paintings. Slavery, Chicago’s gangs, civil rights activism, and animal rights were the colors of her palette. The DAI exhibition is an overview of how these subjects played out in her work. This fall, her son, Robin Washington, the former editor of the Duluth News Tribune now writing for The Boston Globe and host of a Wisconsin Public Radio show, has given talks that shed light on Jean’s unique life and work. Washington says it wasn’t until he was in his 30s that he realized how atypical his family was as he was growing up, and not just because he had a Jewish mother and black father. We asked him to share his insights about the artist and her family, with the aim of shedding light on the DAI show.

Reader: Jean seems to have been comfortable getting outside her comfort zones. I’m thinking here of having members of two rival gangs meet in her home. What did these encounters entail and what were the rewards she experienced by stepping outside her comfort zone?

Robin Washington: As the exhibit notes, Jean was born into privilege, though the family later lost the money. So you could say she was decidedly less comfortable in the traditional sense by the time she invited gangs to our house. She also loved teaching and reveled in talking about everything from gravitational collapse to Chinese art perspective to the feminist aspect of the War of the Austrian Succession to anyone who would listen, especially young people. Still, as much as I know about her, I’m not completely sure what made her so committed to human and even animal rights at such an early age. She was in debates arguing for African American equal rights as a teen in the 1940s, and she was advocating for animal rights before that. A lithograph I only discovered just before this exhibit opened is her earliest known work, from 1938. There’s an animal story behind it, though I’m not sure what.

Reader: What were some clues that your family was in a different place from many Americans in the way you saw things?

Robin Washington: Both my parents worked very hard, by example more than anything else, to convey to us that we were normal. We even shared Passover seders with another black and Jewish family. I now know that simply growing up in Chicago, during the riots and protests, let alone having a front-seat to them, was not at all normal. The first inkling that we might see things differently came when a TV movie about the Rosenbergs aired when I was 14. Two kids at school were talking about it, saying, “I’m glad they killed them.” I was astounded. My left-leaning family very much identified with the Rosenbergs (there were two sons in that case, too). That was a rude awakening.

Reader: Was your neighborhood in the city itself? Your mixed-race parents lived in a “white” neighborhood. What was the location in terms of proximity to the segregated black community?

Robin Washington: The Near North Side, where both my parents grew up, was always integrated, though not every block of it was. When my parents bought our house, it had a restrictive covenant on it (which is part of the exhibit). She shopped for the house and the seller didn’t find out my father was black until closing. We became the first black family on the block and later, when the neighborhood changed, we were the last white family there. By the time my mother sold it 35 years later, it was regentrifying, and we were one of the few remaining black families.

Reader: What was your father’s occupation and how much was he involved with your mother’s unusual involvement with the Lords and Cobras?

Robin Washington: My father, Atlee, had been a (non-flying) officer of the Tuskegee Airmen. He was a published poet yet worked as a chemist and later had his own plastics factory. He and my mother divorced when I was two, but they never lived more than a mile apart from each other. I remember hearing the term “broken home” and not having any idea what it meant, since I saw each of my parents every day (or not, if I didn’t want to). My father was active in left-wing circles in the 40s and 50s, though not organizations like the NAACP and CORE as she was. Though he may have been critical of her interpersonally in the first years after their divorce, he didn’t object to what Jean was doing, and never questioned her taking my brother and me on marches and protests.

Reader: In what sense was Jean’s work considered a movement?

Robin Washington: The “Birkenstein Arts Movement” was coined by the Duluth Art Institute staff for the companion program of classes teaching activism through art for middle school students. They announced it to me, knowing I would cringe a bit because I’ve written about the word “movement,” including analyzing why certain actions do or do not grow into full-fledged movements. But that said, I can see how people inspired by Jean’s art and her activism and could build a curriculum around it. Also, sitting in on some of the middle-school classes impressed me to hear them discuss many of the tactics she and her contemporaries used. So if this knowledge, from Jean or otherwise, helps foster activities that someday become a movement, especially one informed by art, all the better.

The George Morrison Gallery is located on the Fourth Floor of the Historic Duluth Depot. The show was curated by Amy Varsek and Robin Washington.

| Tweet |