News & Articles

Browse all content by date.

Hot sun beat down on the back of my neck, and a mosquito pricked at my elbow. Still, I held my breath and clicked the camera’s shutter-release button twice more before straightening up out of my crouch and swatting the mosquito. The tiny wasp I’d been trying to catch in the act of nectaring zoomed off. This time of year the pollinator gardens at the Cable Natural History Museum are simply buzzing with life.

Several times each day I’ve found excuses to wander outside and check on our bee cabinet and the drama unfolding with flower-eating caterpillars and caterpillar-eating wasps. We’ve had a steady stream of families going to and from our new Curiosity Center, so I can usually justify my visit to the pollinator garden by showing moms, dads, and 8-year-olds the gruesome tale of wasp larvae eating comatose caterpillars.

Once the families move on, though, I go right back to scanning the gardens for anything interesting. Dragonflies often hover above the grass, and a particularly brave one once perched calmly on the tip of a caterpillar-eaten figwort plant while I played paparazzi. It’s yellow and orange body was contrasted by beautiful burgundy wing spots, and bright white pterostigmata. These little rectangular patches of thicker, heavier, cells at the leading edge of each dragonfly wing help to prevent the wings from vibrating at high speeds. I love seeing a pterostigma just so that I can say the word to myself. The silent P is my favorite part. Ptero- relates to wings, and a stigma is a mark or spot. But saying “wing spot” just isn’t the same.

A monarch butterfly caught my attention, too, and as I followed it around to the patch of yellow coreopsis flowers, a new butterfly caught my eye. With wings of yellow shading to orange, overlaid with a striking pattern of black lines and spots, I couldn’t help but snap a few photos of it, too.

While leaning over some false sunflowers to see the butterfly, a break in the pattern caught my eye. How odd! Three inches of a flower stem, just under the blossom, were lined with tiny critters. Their oval bodies were red-orange, and their wiry black legs stuck out at odd angles. As I looked more closely, I guessed that they were aphids, since each one had a straight, black mouthpart inserted into the plant stem. I snapped a few photos of those, too, using my macro setting to capture the detail.

Once back at my desk, I alternated between responding to emails and uploading the photos. Feeling too rushed to flip through the selection of field guides on my shelves, I opted for a different route. I logged into my iNaturalist account, and uploaded the best photo of each critter.

The description on their website summarizes that, “iNaturalist is an online social network of people sharing biodiversity information to help each other learn about nature.” They have an app as well as the website, and both can be used to upload photos of living things. The photos get geotagged, identified, and become observations. Then an extensive network of naturalists, citizen scientists, and biologists can check your identification, add their own ideas, and use everyone’s data to do research.

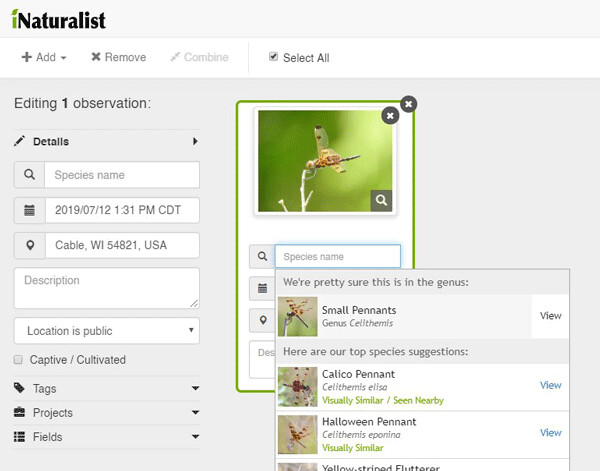

With more than 23,486,900 observations around the world, iNaturalist has seen a lot of living things. That allowed the developers to create an automated species identification tool. It combs that database for things that are both visually similar to your photo and have been seen nearby by other observers. What that means for amateurs like me, is that when I clicked in the “species name” box under my photo, a list of suggested identifications came up. “We’re pretty sure it’s in this genus: Small Pennants, Celithemis,” was the helpful comment, and below that, “Here are our top species suggestions:” Within seconds, I was pretty sure that I’d photographed a calico pennant dragonfly.

After identifying my purple-lined sallow moth caterpillars, dark paper wasp, Aphrodite fritillary butterfly, aphids in the genus Uroleucon, and several more, a Facebook message pinged. My childhood friend in Omaha sent photos of fuzzy caterpillars on milkweed for identification. I uploaded that photo, too, and iNaturalist gave me the tentative ID of “tussock moth caterpillars.” After she posted 10 more photos of insects in her pollinator garden, I clued her into the iNaturalist trick, too.

Then an automated email from iNaturalist notified me that my calico pennant observation had been added to a project called “Odonata - parasitism.” Looking closer at my photo, I saw several clusters of dark bumps under the dragonfly’s body. A quick Google search informed me that larval water mites often attach to a dragonfly for a meal and ride – not unlike ticks on humans. I’d never have noticed those mites without the extra eyes of iNaturalist participants.

This summer I’ve had a number of people comment about how much I know, or should know about nature. Naturalists are generalists, though. I can tell you a little bit about just about everything, but there are a whole lot of details that I can’t even begin to remember. One of the most valuable skills of a naturalist is knowing how to use the resources available to answer questions. Sometimes that means paging through a guidebook or asking an expert, and sometime that means submitting a photo to a computer algorithm. The fun part is that iNaturalist is available to anyone at any time. And just following your curiosity by uploading photos to get ID help will result in data that may someday be used for important science. Want to join in the fun? Now’s the perfect time – summer is just buzzing with life!

Emily’s second book, Natural Connections: Dreaming of an Elfin Skimmer, is now available to purchase at www.cablemuseum.org/books and at your local independent bookstore, too.

For more than 50 years, the Cable Natural History Museum has served to connect you to the Northwoods. Come visit us in Cable, WI! Our new Curiosity Center kids’ exhibit and Pollinator Power annual exhibit are now open! Call us at 715-798-3890 or email emily@cablemuseum.org.

| Tweet |