News & Articles

Browse all content by date.

“Are you going to dress someone up like an animal again?” asked an eager fifth grader at Drummond Elementary this week. I’d called on the student with his hand up because I was hoping that he’d answer the question I had just asked: “What do you remember learning on my first two visits to your classroom this year?”

Jane Weber, our MuseumMobile Educator, recently developed three new lessons for our fifth grade classroom visits. In the fall, students learned about white-tailed deer, and practiced deciphering a deer’s age by the teeth in cleaned jawbones. For our winter visit, we dressed two students up like fish, and compared the adaptations of prey fish (sharp spines, laterally compressed bodies, and eyes on the sides of their heads) with predator fish (sharp teeth, torpedo shaped bodies, and eyes on the front of their head).

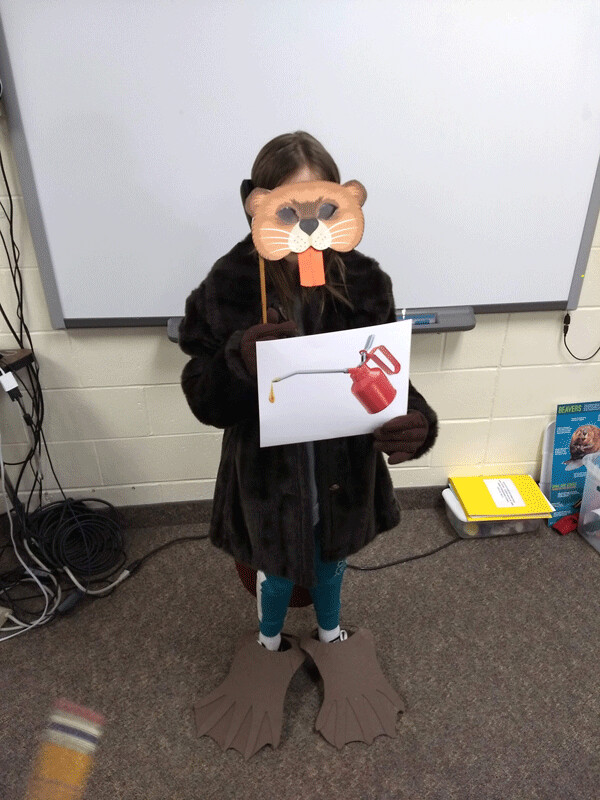

Now, for our spring lesson, we were about to learn about beavers. Like all animals, beavers have an impressive suite of adaptations that help them survive in their habitat. As teachers, Jane and I have adapted to a 5th grader’s sense of humor, and designed the lesson around dressing a kid up like a beaver.

I started with the feet. Beavers’ hind feet are webbed, of course, to help propel them through the water. Oddly, they also have a split nail on their second toe, which acts like a comb for spreading oil throughout their fur and removing debris. That oil is very important to beavers as they swim underneath the ice all winter long. Without it, they would be wet and chilled to the bone. So, after fastening two giant foam webbed feet around my victim…er volunteer’s ankles, I also handed her a photo of an oil can.

Two brown gloves went on next. Beavers have surprisingly dexterous hands that they use to bring mud to their dam and lodge, to hold twigs while eating, and to dig out deeper channels for swimming.

The class roared with laughter when I pulled a fancy faux fur jacket out of my tub. These students have been growing up in our MuseumMobile program since they were in pre-K, and some of them remembered feeling the soft pelt of a beaver in their early years. One girl gazed off into the distance as she described the soft, warm underfur of her memory. Another piped right in to tell me about beavers’ longer, shinier guard hairs that help shed water.

Jane had sneakily sewn a strip of Velcro under the back hem of the jacket. To this, I affixed a giant, flat, brown beaver tail, which also got a laugh. I also pulled a real (dried) beaver tail out of my tub to show around the class. They’d also seen this in kindergarten, but beaver tails never get old. Of course one kid peered at the cut end and exclaimed in disgust. Beavers use their tails for fat storage, and the now desiccated fat isn’t exactly pretty. But it was useful when the beaver was alive. That fat fuels their metabolism during the long winter to help them stay warm.

The students easily came up with three more uses for a beaver’s tail: swimming rudder, warning signal, and a kick-stand to help them balance when cutting down trees. Their tails also help beavers dive quickly under the surface, and help them stay cool in the summer. One thing that a beaver tail isn’t useful for: patting mud onto their dam and lodge. Only cartoon beavers do that.

Before handing our beaver her Mardi Gras-style mask on a stick, I brought out a real beaver skull. This isn’t the first time these students have seen that exact skull. It’s neat to provide continuity through the years. In kindergarten they have their first introduction to beavers, admire the skull, and feel the stick that’s been de-barked by a beaver’s teeth. In second grade we bring out the beaver skull to illustrate how the teeth of an herbivore differ from that of a carnivore. In fourth grade, when we dissect owl pellets and find lots of little mouse skulls, I show the beaver skull as a bigger example of a rodent’s orange front teeth.

Today we look more closely at the skull, and talk about the iron that stains the teeth orange, giving them added strength. We also note that the eyes, ears, and nose of a beaver are all sitting right at the top of its head. Even while swimming with their body completely submerged, beavers can have all of their senses attuned to danger.

Before I hand our volunteer her mask, I ask the kids how many of them use goggles for swimming. Beavers have built in googles, I tell them, and of course we’re all jealous. I’ve never met a pair of goggles I like. But beavers have a third, clear eyelid, called a nictitating membrane. It protects their eyes from debris while they swim. I show the class a clear plastic lens covering the eyes of our beaver mask, then hand it over to our busy beaver.

The last prop is a pair of ear muffs. Water in your eyes isn’t the only issue. Beavers have valves in both their ears and nostrils to keep the water out while diving. Now we’re all seriously jealous, as we commiserate over how terrible it feels to get water up your nose or stuck in your ears while swimming. Beavers may look a little odd, but they have some sweet tricks up their fur.

Our completed beaver now spins slowly to show off her adaptations, and we applaud her cooperation before dismantling the costume.

Then I pass out bingo cards filled with pictures of animals. The dams that beavers build, and the ponds that fill in behind them, are incredibly valuable habitat for countless species. I start calling off animals that rely on beavers: songbirds, wood ducks, kingfishers, mink, dragonflies, great blue herons, deer, pileated woodpeckers, and water lilies. At this point, the entire class is on their edge of their seats, just needing one more square to win. Of course, I’m chuckling to myself, because I designed three different bingo cards that would all win at the same time. “Leopard frog!” I call, and the class erupts.

As I clean up my supplies and wrap up the class, I’m still chuckling to myself. “Bingo!” I think to myself. Jane did a great job designing a lesson to teach fifth graders about the amazing adaptations of beavers.

Emily’s second book, Natural Connections: Dreaming of an Elfin Skimmer, will be available in March! Listen to the podcast at www.cablemusum.org!

For 50 years, the Cable Natural History Museum has served to connect you to the Northwoods. Come visit us in Cable, WI! Our new exhibit: “Bee Amazed” is now open!

| Tweet |