News & Articles

Browse all content by date.

The only things fluttering around the Museum’s pollinator garden recently are snowflakes. Dried stalks of beebalm remind me of how vibrant that corner of our yard becomes by midsummer. Currently, the flowers are topped by little puffs of snow instead of fragrant purple petals and buzzing bees. Inside the Museum, though, we’re planning an exhibit all about pollinators. Even while traipsing all over Alaska last summer, I was thinking about pollinators.

And that’s how I ended up in a yurt, in Denali National Park’s Teklanika River Campground, at Mile 29.1 on the park road, listening to a presentation about “Fur Bearing Insects of Denali.” The instructor, Jessica Rykken, is Denali National Park’s official entomologist—charged with surveying, collecting, and archiving insects in the park. Denali’s 17 species of bumble bees represent one-third of all the bumble bee diversity in North America, and they are charmingly furry.

The fur is for more than just looking cute, though, as Jessica explained. Just like my favorite wool sweater, the thick coat of hairs on a bumble bee provides insulation and allows them to be active at colder temperatures. Their relatively large body size makes it easier for bumble bees to retain heat as well. Using these adaptations, and by shivering their large flight muscles, bees can raise their body temperatures 60 degrees Fahrenheit above the air temperature! “I dress in a wool hat and full rain suit to go collecting bees!” commented Jessica.

She wasn’t joking. Outside the yurt, the picnic table sported a light glaze of frost, even in late June. The small group of naturalists taking this Alaska Geographic Field Course wore rain jackets, puffy coats, down vests, hats, gloves, and mittens. Hiking uphill to some of Jessica’s study sites helped us warm up briefly, but intermittent sunshine and drizzle had us adjusting layers frequently. We still found insects!

Staying warm in the summer is one thing, but bees need to survive harsh winters in Denali, too. New bumble bee queens mature in late summer, mate with a male drone bee, excavate a small hole in the ground to hibernate in, and produce anti-freeze to keep from freezing as winter descends. Queens who survive the winter emerge in early spring and begin the process of starting a new colony.

Bumble bees need both nectar and pollen to fuel themselves and feed their colony. They’re able to forage on a wide variety of flowers, which helps make sure that there’s always a snack blooming nearby. While you might expect that only a few types of flowers can survive in the harsh environment of tundra, these low-growing plants that carpet the mountainsides and arctic slopes are the most diverse habitat in the state. As glaciers came and went across the continent, tundra habitat was always present somewhere in Alaska, and tundra flowers didn’t have to complete a long migration to recolonize places scraped clean by sheets of ice.

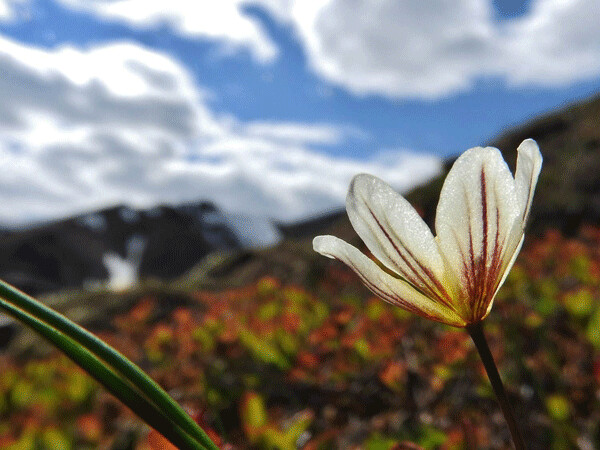

In such a cold environment, even flowers need ways to stay warm. The bowl-shaped blossoms of Arctic poppies and many other species are essentially solar collectors, and they can warm up quite nicely on a sunny day. Some flowers even track the path of the sun. A warm blossom can have many benefits. The heat will enhance evaporation of floral scents, which attracts some pollinators. A cold pollinator who drinks warm nectar gets a double energy bonus; similar to how hot chocolate warms us from the inside out.

I like to imagine a cold bee curling up inside a warm blossom for a nap, but one study found that the ground is an even better place for insects to bask. My classmates and I experienced that firsthand. We started by kneeling to look at an insect, and then slowly lowering ourselves down out of the wind onto the cushioned surface of the mountainside into a warmer microhabitat.

In reality, the ability of a flower to warm up may benefit the flower more directly than by attracting pollinators. Although flowers don’t need to warm up flight muscles in order to move, they develop faster at higher temperatures. Added warmth can help the pollen to germinate, help the pollen tube to grow as it searches out the ovule for fertilization, and help that ovule to develop into a fruit and seeds. All of those processes need to happen quickly, before the short Arctic summer descends back in to winter.

It seems like everyone and everything in Alaska shares that same overwhelming desire to pack as much into summer as humanly (or naturally) possible. Our insect class made use of long, midsummer days by collecting bugs until 10:00 p.m. Bumble bees dress in wool to go foraging. Tundra flowers make seeds while the sun shines. And I zoomed around with my camera and notebook, storing up memories to fuel my learning in the long winter ahead.

Emily’s second book, Natural Connections: Dreaming of an Elfin Skimmer, will be available in March! Listen to the podcast at www.cablemusum.org!

For 50 years, the Cable Natural History Museum has served to connect you to the Northwoods. Come visit us in Cable, WI! Our new exhibit: "Bee Amazed" is now open!

| Tweet |