News & Articles

Browse all content by date.

Recently, Lake Superior Zoo CEO Erik Simonson informed the city that the zoo wished to abandon its current guiding plan in order to proceed in what they felt was a better direction. The guiding plan, approved in 2016, called for the flood-damaged zoo to reduce its footprint from 19 acres to 10 acres, and to convert all the zoo property west of Kingsbury Creek into a free public park. As this plan had been the culmination of more than a year of negotiation between the city and the zoo, as well as the subject of numerous public meetings and a vote of the City Council, the change in direction was a surprise.

In comments that Simonson made to the Parks Commission on Nov. 14, 2018, one reason he gave for abandoning the 2016 plan (which was approved before he was CEO) was financial. The 2016 plan had put the price tag for a zoo refurbishment at $15 million, but more accurate estimates now suggested that the true cost would be “in the neighborhood of $25- to $28 million”—which was more than the zoo could afford. The cost of a single signature exhibit, Bear Country, had originally been pegged at $2.5 million, but the true price tag was coming in at $4.8 million.

“I’m not saying this is anybody’s fault,” said Simonson. “It’s just cost estimates are what they are. Oftentimes when you’re preliminary in a project, you end up with numbers that perhaps aren’t exactly reflective of what the costs actually are … I don’t blame anybody for that. It is just the circumstances, the way they come to be.”

A second reason Simonson gave for wanting to depart from the 2016 plan was practical. The 2016 plan called for “creat[ing] a larger collection of smaller animals,” but that strategy was “not necessarily conducive to increasing attendance,” in Simonson’s view. Visitors liked to see bigger animals, and bigger animals needed bigger enclosures. Without the land west of Kingsbury Creek, the zoo would have limited space for bigger exhibits. Their ability to expand in the future would also be restricted.

Currently, the zoo had about $4 million available to use for capital improvements, Simonson said—$1.9 million from the city’s half-and-half tax, $1.9 million from a state bonding grant, and $200,000 from fundraising. He said the zoo wanted to use the $4 million to rehab and expand existing structures to use for animals like black bear and river otter. Space for the existing snow leopard and lynx would also be expanded. The zoo hoped this investment in charismatic fauna would give them a much-needed boost in attendance, which would help reduce their reliance on city subsidy.

“I don’t see a viable alternative, other than to go down this path,” said Simonson. “It makes the best use of … funds that are available to us and it provides the zoo the best chance for success going forward.”

City staff had been closely involved with earlier zoo planning efforts, but this time around, according to Director of Public Administration Jim Filby Williams, the city would largely defer to the Zoological Society.

“We will step back … and let them lead that process,” Filby Williams told commissioners. “From the administration’s perspective, we have a strong interest in the long-term success of the zoo. And the Zoological Society leads the charge there. We entrust and burden them with the responsibility of stewarding that place and keeping it alive. And so when they say to us, ‘In order for us to be successful, we need you to give us this additional space and latitude,’ we think it is wise and appropriate to be reasonably deferent to that wish … The zoo’s been struggling for several years, and we don’t have an unlimited number of years or number of attempts at saving the zoo, and so there is a level of urgency to give our partners at the Society what they say they need to succeed. That’s the administration’s view.”

The high cost of going in a circle

In many ways, planning at the zoo has come full circle.

The city owns the zoo, and until about ten years ago, operated it, with the private nonprofit Lake Superior Zoological Society playing a supporting role in terms of fundraising and advocacy. In 2009, the city found itself facing severe budget challenges brought on by the national recession and other factors. As one of many strategies to deal with the crisis, the city turned over management of the zoo to the Zoological Society.

On June 20, 2012, the Great Flood hit the zoo hard. Kingsbury Creek rose and backed up from Grand Avenue, drowning 14 animals and doing permanent damage to the zoo’s signature polar bear exhibit, Polar Shores. The zoo was forced to close for several weeks during its busiest time of year to deal with the aftermath. Polar Shores was never repaired, and zoo attendance dropped considerably.

In 2014, saying he wanted to “start fresh” with the struggling zoo, Mayor Don Ness ordered zoo staff to halt work on all current projects. The mayor had a vision of getting rid of the animals, removing the fence, and opening up the grounds of Fairmount Park to the public. The Zoological Society objected, saying they wanted to stay a zoo. As the months passed, city administration and zoo leadership remained divided over this fundamental question of whether the zoo should exist.

In November of 2014, following several stakeholder meetings, a consultant produced a report saying the zoo could be revitalized for an investment of $12- to $16 million. Mayor Ness declined to release the report to the public for several months. Meanwhile, he convened a new group composed of only close advisors and hired a new consultant to produce a vision more to his liking. The second report, which came out in April of 2015, offered concepts for a Fairmount Park without animals, the zoo’s spaces repurposed into play areas and brew pubs.

In the end, the zoo’s supporters largely prevailed. After listening to their outcry, the city hired a third consultant, who in 2016 produced the plan for a reduced zoo footprint east of Kingsbury Creek and an open public park to the west. This is the plan that CEO Simonson has now rescinded. Essentially, we’re back where we were in 2014.

We’ll see how it all works out. In the meantime, it might be fun to add up how much money we’ve spent on reports.

The 2014 report, by ConsultEcon, cost $59,000.

The 2015 report, by HKGI, cost $37,800.

The 2016 report, by Hammel, Green and Abrahamson, cost $128,400.

Total cost to achieve nothing = 59,000 + 37,800 + 128,400 = $225,200.

The rule, not the exception

Mr. Simonson said that he didn’t blame anyone for producing early estimates that were too low. In his own remarks to the Parks Commission, Mr. Filby Williams concurred.

“It’s not uncommon,” he said. “God bless engineers and architects, but their cost estimates are often off. They’re often rather low … I do think that kind of disconnect between original estimates and actual bids is the rule, not the exception.”

Another recent project has shown a similar disconnect: The new Nordic Center at Spirit Mountain. Originally forecast to cost $1.5 million, the Nordic Center’s price tag came in at $3.2 million when it was bid out early this year. The city responded to the massive gap, not by shelving the project, but by dividing construction into phases and promising to come up with the rest of the money later. Phase One is well underway.

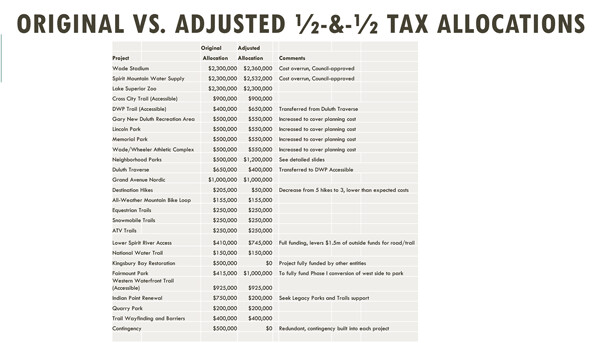

Sometimes the City Council and the public become aware of discrepancies between costs and estimates, and sometimes they do not. Spirit Mountain’s water line is one project where the cost crept up without anyone really noticing. When the City Council approved funding for the water line in 2014, they approved a bond issue of $2.1 million. Nine months later, when the Council approved a list of River Corridor recreation projects, the water line appeared on the list, but now with an earmarked amount of $2.3 million. And more than a year after that, when the water line appeared briefly in a staff presentation to Council, the price tag had increased to $2.532 million. It went up 20 percent without note.

Smaller projects, too, follow this path. An all-weather mountain bike trail which was recently completed at Spirit Mountain had $80,000 allocated to it in the City Council resolution approving the project. When the project was finished, however, the final price came in at $116,000—45 percent higher. The City Council did not approve any increase, but the bills were paid nonetheless.

A historical gotcha?

When I say that the cost of the Spirit Mountain water line increased to $2.532 million, I get that figure from a single appearance that it made in the public record (as far as I know) on June 13, 2016. During a Committee of the Whole meeting before the Duluth City Council, then-Parks Director Lindsay Dean showed a slide which showed that funding for the water line had increased from $2.3 million to $2.532 million. She didn’t offer much explanation, though. All she said was: “There have been funding increases for projects with cost overruns. The projects that fall into this category are Wade Stadium and Spirit Mountain water supply, both of which are now complete.” That was all. No details provided, no reasons given. Essentially, the numbers just floated by.

A closer examination of the slide itself, however, reveals something that Dean didn’t mention. Next to the $2.532 million figure, a note says: “Cost overrun, Council-approved.”

In reviewing Council actions for the years 2014, 2015 and 2016, I am unable to find any evidence that the Council ever approved a cost overrun for the water line. Right now, it appears that this claim from a 2016 slide show was false.

At this late date, does it matter? I’m probably the only person who still has a copy of the slide show left. Ms. Dean didn’t actually mention the falsehood aloud; she breezed past this slide pretty quickly. It may not have even been her slide, as staff often collaborate on presentations. It’s probably no big deal. It’s just another example of how things like this slip through. Somebody else digging through the historical record might find it and believe it.

Good city

Regular readers know that I often moan grievously about the lack of transparency that I find within the shadowy hallways of government. Thus, talking about positive developments gives me great pleasure.

Regular City Council meetings on Monday nights are understandably high-profile affairs, where the public weighs in on issues and votes are taken. But far more informational and useful than regular Council meetings are the Council’s agenda sessions, held on the Thursday prior. At agenda sessions, councilors question city staff about items on the agenda, and all kinds of juicy stuff can fall out of the conversation. Reporters are often the only people in the audience.

The Council’s agenda sessions are open to the public, as they should be. Until quite recently, though, only the recording of the most recent agenda session was available online. Each new agenda session recording would replace the one before it, and no archive of agenda sessions was maintained.

This changed in January of 2018. City Councilor Noah Hobbs took the initiative to ask the city if they would establish an archive of agenda session recordings online, and they said they would. (I don’t know if that’s exactly how it happened, but close enough.) Several months of agenda sessions are currently available on the city’s website, along with recordings of various committee meetings, which also used to never be found. The general public may not get excited about this, but that’s only because they don’t know what’s good for them. Being able to listen to meetings online is a huge time-saver! The city should put commission meetings online next.

| Tweet |