News & Articles

Browse all content by date.

One of the neatest things about having a friendly conversation with nationally known auto journalist Tony Swan was that you might occasionally have a disagreement. You could debate for a while, then suddenly Tony would look you in the eye and say: “Well, you’re wrong!”

End of discussion. Tony always lived his life by his own rules, and that carried over to friendships and arguments.

Tony also had a passion for cars, especially fast cars, racing cars, and he enjoyed testing all kinds of cars on all kinds of road-racing tracks. But he mostly enjoyed keeping things simple behind the wheel. He was an excellent driver, and except for a few speeding tickets now and then, he didn’t get reckless driving on the streets.

His car of choice? Whatever he could test drive most recently, and his own car of choice was a Volkswagen GTI, the no-compromise performance model of the Golf. Inexpensive, comparatively speaking, and with a six-speed stick shift because it was most fun, gave him most control, and was the simplest version.

Those of us who have spent a lot of years reporting on new cars lost a star out of our galaxy last week when Tony Swan, weakened to a point of unwilling fragility after a long battle with cancer, spent most of his final week in gentle hospice care. After conveying final farewells to his wife, Mary, and his gathered kids from an earlier marriage, Tony allowed himself to relax and slip away overnight.

Tony and Mary lived in Ypsilanti, Michigan, close enough to Detroit, the nation’s automotive nerve-center. At age 78, Tony had eased back from his writing at Car & Driver magazine; I was never sure it was his own call, because he gave way to a new generation, but was still free-lancing wherever he could.

Writers rarely talk or write about other writers, but I go back to college days in my friendship with Tony, so I’m allowed. Anyone who read about cars for the last few decades has read something by Tony, maybe in Car & Driver, or maybe Motor Trend, or maybe even back to his AutoWeek days. Others will write about what a great guy he was, a warm human behind that curmudgeonlike demeanor. I will simply say that he was the best writer for every publication he worked for.

Tony grew up in the western suburbs of Minneapolis, and back in the 1960s, he and I both attended the University of Minnesota to study journalism and prepare to write our way into careers. He was a couple years older than I, but we both loved cars and sports, and we hit it off in unusual fashion. We both had a cynical sense of humor, and we could crack each other up anytime we got together. About the time I left a two-year experience writing at the Duluth News Tribune to accept an offer from the prestigious sports department of the Minneapolis Tribune, Tony got a job writing sports at the St. Paul Pioneer Press.

The papers were bitter rivals, but Tony and I were friendly rivals even while competitive in print, covering hockey all winter and motorsports all summer. In act, we both went through road-racing school in the early 1970s. We never told our papers, but when we were sent off to cover Glen Sonmor’s University of Minnesota hockey team establishing a heated rivalry with Badger Bob Johnson’s Wisconsin outfit, Tony and I would share a drive from Minneapolis to Madison. That way we could keep each other awake when we drove home after the Saturday game. More likely, we kept each other in stitches, particularly when we’d make a stop for soup, a sandwich, or a piece of pie at Grandma Smrekar’s all-night cafe at Millston, Wis. Invariably, we’d end up laughing like fools over something that a normal human might find inconsequential.

Tony left the Pioneer Press to try an over-zealous attempt to turn a suburban paper into a special-edition sports blockbuster. It didn’t work and was disbanded, leaving Tony out of writing while I was cruising on an upward trajectory writing sports and an automotive column for the Tribune. I was flattered that management, advertising, and, most importantly, readers enjoyed my take on new cars.

Then my phone rang and it was Better Homes & Gardens, the huge, slick and world famous magazine, produced in Des Moines. They had an auto column every month, and they wanted to hire me to write it. They flew me to Des Moines, Iowa, and made me a very solid offer. Only stipulation was I couldn’t mention any brand names. I paused, because at the time I was writing up the best hockey games every night all winter, and auto racing all summer, and my auto column year-round. Trouble was, unlike Tony, I loved cars and hockey equally and couldn’t see giving up sports and cars for just cars.

So I turned them down, but I suggested that I knew an exceptional writer who might be perfect for their job. I told them how to reach Tony Swan. He jumped at it, and stayed with it as it grew into a regular western travel feature, moving to the West Coast. I never regretted being able to cover hockey and cars, my joint loves, while Tony found the West Coast a perfect launching pad to join AutoWeek, then Cycle World, then Motor Trend, before relocating back in the Midwest in Detroit to write for Car & Driver.

Our time together was rare, but we stayed connected at auto shows and other places. One time Tony was doing a lengthy report on a Peugeot diesel, and he drove it form Detroit to Minneapolis, timing his trip so he could visit his family on Lake Minnetonka and cover a road race at Donnybrooke Speedway, where we had both learned to race in the early ’70s driving Showroom Stock Sedans.

Those of us who regularly made that trek took the smaller but faster and less-traveled Hwy. 25 north off the freeway and straight into Brainerd. The Peugeot Diesel was a great long-running car but not fast, being before turbocharging came into fashion. So when Tony stepped on the gas, there was no evidence the pedal had any connection to the engine for a mile or so.

The only car on the road with him was just ahead, some guy who didn’t want his big American car to be passed by that foreign thing. Whenever Tony came up to pass him, the other car would accelerate hard to stay just ahead, then slow down until Tony would try again. It was so maddening to Tony that plotted ahead, where he knew of one particular 4-way stop in an otherwide deserted rural area. Approaching that intersection, you could see for a mile both ways on the crossroad. So Tony backed off a bit, and just as the other driver slowed to stop, Tony sailed past him in the oncoming lane, flying through the four-way stop and settling that issue.

Swan was one of the founders of the North American Car of the Year award, given out every year since 1993 by a panel of selected journalists. In its second year, Tony called me and invited me to join. I was flattered, and enjoyed my 13 years on that jury, pressing several suggestions that helped advance the selection process and gain publicity for the award. When a fellow decided to cut me from the group, for his own reasons, Tony led a group that argued in my favor, and I’m forever indebted to him for his guidance in what had become a hotly political group.

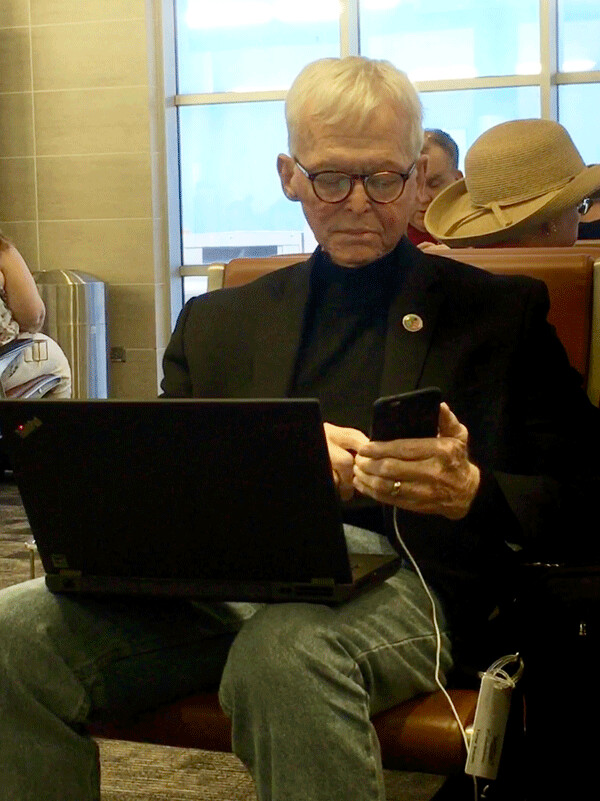

I was flown to San Antonio for a new vehicle introduction early in 2017, and as I left my plane and entered the gate area, I spotted Tony sitting in a chair, writing something on his computer while he operated his cell phone, which was plugged in recharging. I couldn’t resist shooting a photo of it, because Tony didn’t see me, and I knew that while he looked like Mr. High Tech at the time, he hated all these new-fangled devices.

By then, Tony had been diagnosed with cancer, and explained it to me in considerable detail. He was optimistic about beating it, and continued testing cars, writing about them, and racing in his vintage class. He did fight it, but it was sinister. He’d pursue the treatement for one form of cancer but the dreaded disease would circle back and strike somewhere else.

All the while, his weight, and his strength, were being diminished. I tried to cheer him up to keep fighting, knowing well that he would, by phone calls, e-mails, or phone messages.

A month ago, after reading an intriguing article on immunotherapy and its potential to fight cancer, I sent Tony a text message asking if he’d ever tried it. He responded brusquely: “I’ve had experience with two differnt immunotherapy drugs, with very little luck...Who is this?”

I apologized and said I had sent a text message to his phone because I wasn’t sure the e-mail had gone through. He responded to thank me for the thought and explained he was doing daily radiation for a month, “...to shrink a series of surface tumors marching down my chest...I’m pretty close to out of options. If I’m lucky with these treatments, maybe I’ll see another birthday. (May.)”

Later, I explained some neat technical features on a vehicle I had tested at an introduction he had been unable to attend, and I used text messaging again — my family’s favorite method of communication. Tony responded and talked about other models that had been engineered impressively.

The he abruptly wrote: “Where did you get this numbered e-mail? Not a good idea, in my estimation.”

I sent him yet another message, saying: “...this is text-messaging, a seemingly more efficient if trendy contact method.”

Then I realized, here was this master auto reviewer who still didn’t like things that were fancier than need be, and he had never heard of text messaging, much less engaged in it. Numbered e-mail? I loved it.

He and Mary drove to the Twin Cities to see some family, and to attend a Gopher football game. It was perhaps too much for him, although Mary hustled him around by wheelchair. On their return drive to Ypsilanti, Tony had some serious issues that caused them to make a side-trip to the Mayo Clinic. They get him together to try the rest of the long drive, and Mary noted on his Caring Bridge page that he had finally agreed to go right into hospice upon their return.

She also alerted us that the end was near in midweek last week. Joan and I talked about it, both knowing that our attempts to send cosmic energy was futile. I sent him a final note — by e-mail, this time — recounting Grandma Smrekar’s and other good times in our past, told him we would keep hoping for a miracle, but if he had gotten weary of the fight, we hoped he could find some pain-free way to relax and rest, and closed with: “We love you, man.”

I went to bed and slept hard, but I woke up four or five times, with my thoughts focused on Tony Swan. When it was time to get up, I noted the trees in our yard blowing back and forth with great force from the swirling wind. Then we spotted a notification from Mary that said Tony had peacefully ended his battle overnight.

It called for one final message to Mary, where I offered our sincere condolences, and polnted out the oddity of waking up repeatedly focused on Tony, and then saw the trees being blown back and forth. I submitted to her that Tony will always be with us, and my take on the wind-blown trees was that it was Tony making one more lap around his beloved Minnesota.

Rest easy, Tony.

| Tweet |