News & Articles

Browse all content by date.

Frost sparkled on the picnic tables at the Alaska Geographic Field Camp in Denali National Park and the thermometer still read 30 degrees Fahrenheit even though the sun had risen four hours earlier at about 3:00 a.m. In pairs and trios, ten women bundled in puffy coats and winter hats emerged from tent cabins tucked into the white spruces and converged on a small yurt where Susan, our Alaska Geographic naturalist, had just brought out the coffee.

Over hot cereal topped with pecans, cranberries, and yogurt, we discussed our plan for the day. The cold snap had fueled doubt among us students that we would find many wildflowers blooming in alpine areas. Carl Roland—botanist for Denali National Park—just smiled knowingly. Spotting a small, white flower with a bluish cast to the undersides of its six, cream-colored petals gave me hope, though. Carl identified it as windflower—Anemone parviflora—and we put the first species on our list for the Wildflowers of Denali field course.

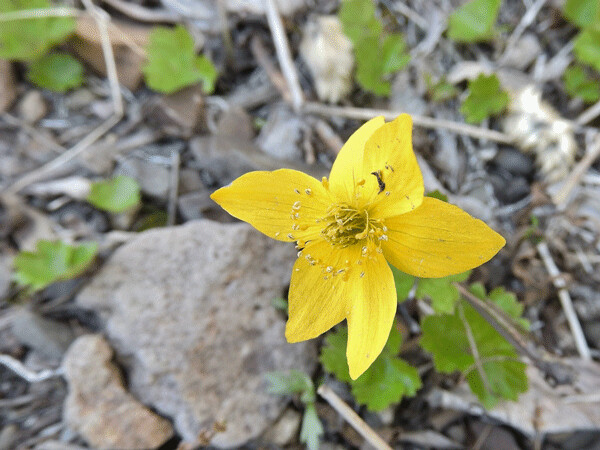

By the time we arrived at the place where Tattler Creek intersected Park Road, abundant sunshine had raised the temperature considerably. Here, Carl pointed out a yellow anemone—Anemone richardsonii—hiding under the willow shrubs. Then we crashed uphill through thickets of thigh-high dwarf birch with dime-sized leaves, stopping often to look at new plants.

It was a relief to climb out of the brushy ravine and emerge onto the open tundra with low growing mats of vegetation. Turning to look around at the snowcapped peaks of the Alaska Range, I reflected on how far I’d come since leaving Wisconsin.

Glancing down, though, I spotted the familiar ovate leaves and bell-shaped flowers of a blueberry bush. With a blueish cast and more rounded shape, these leaves did not belong to the common Wisconsin species of lowbush blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium), but its cousin, bog blueberry (Vaccinium uliginosum). Still familiar to me, I’d come to know this plant while canoeing in northern Minnesota and wetland monitoring in Maine. Someday I’ll travel to Iceland, Scotland, Scandinavia, the Alps, Russia, and Japan to visit my little friend in all of those places.

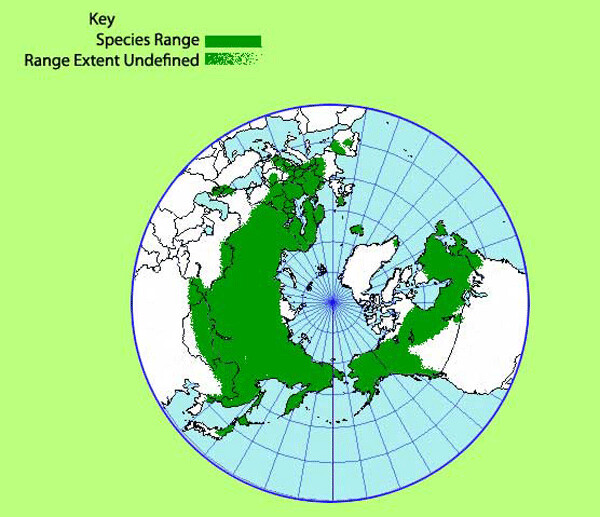

This pattern is known as circumpolar distribution. Bog rosemary, bearberry, cottongrass, twinflower, and stiff clubmoss are some other of my favorite Northern Wisconsin bog species who share a similar global range. Their adaptations to severe cold, short growing seasons, and other challenges help them thrive both at high latitudes (circling the North Pole) and high altitudes further south. If you tilt a globe and look at it with the North Pole in the center, you also see that there’s a lot of land up there. Plants don’t recognize international boundaries.

Beyond the blueberries, a scattering of creamy flowers with bright yellow centers nestled into a mat of hearty, dark green leaves. These rose-relatives are called mountain avens. Immediately I thought about my friend Caitlin who did her graduate research on flowering phenology across the continent in the White Mountains of New Hampshire. Mountain avens are her favorite flower.

This species, Dryas integrifolia (as well as the two anemones we saw earlier), is considered “amphiberingian,” which means that its distribution spans the Bering Strait in North America and northern Eurasia, but doesn’t extend into Greenland or Europe. The Bering Strait was a land bridge that connected Alaska to Russia when sea levels fell during times when more of Earth’s water was locked up in glacial ice. Plants, animals, and even people may have used this temporary travel route. Because it was ice-free and kept relatively warm by the ocean, it was also a refuge where plants could escape the grind of glaciers.

Sunshine warmed us on the tundra, and we spent hours on our knees and bellies identifying carpets of alpine flowers. I needn’t have worried that we find enough to look at—these plants know how to make the most of a short summer.

As we crashed back through the brushy ravine of Tattler Creek, Carl pointed out ruffled leaves and fuzzy buds that would soon bloom into a bear flower—Boykinia richardsonii. This showy stalk of white flowers is a remnant of Alaska’s Tertiary Period forests. It has been growing here for more than 2.58 million years—since mammals became dominant and the continents moved into their current locations.

In Denali, there are 233 plant species—29 percent—who are considered circumpolar. Throughout the park, sparsely vegetated alpine areas support higher plant diversity than lower, warmer places with higher productivity. Doesn’t that seem backwards? Shouldn’t the higher, colder, more extreme environments support fewer plants?

The key here is that during the past 300,000 years, treeless, steppe-and-tundra-like landscapes have been a constant. Other habitats—and their plants—disappeared. The plants that stuck around at the edge of the glaciers were pre-adapted to the conditions in the current alpine zone. They may not have always existed right here on the slopes above Tattler Creek, but their journey to get here would have been a whole lot shorter than mine.

Emily is in Alaska for the summer! Follow the journey in this column, and see additional stories and photos on her blog: http://cablemuseum.org/connect/.

For 50 years, the Cable Natural History Museum has served to connect you to the Northwoods. Come visit us in Cable, WI! Our new exhibit: “Bee Amazed!” is open.

| Tweet |