News & Articles

Browse all content by date.

The sun was hot as I sat on a bench outside the Effigy Mounds National Monument Visitor Center to put on my hiking boots. Entering the woods, though, the cool shade enveloped me. The air was sweet and buzzing with life. After a few deep breaths to enjoy the welcome change in the microclimate, I began by striding up the trail with purpose.

I didn’t get very far. Rosy columbine flowers glowed in the sunflecks. Neon orange orioles chased each other through the canopy. Both purple and yellow violets lined the trail, while may apples, wood anemone, false rue anemone, sweet William, and large flowering bellwort carpeted the forest floor. A big, fuzzy bumble bee queen investigated hollows in the leaves, perhaps still searching for the perfect spot for her nest.

Calcium-rich limestone bedrock poked through black soil on this river bluff, and the canopy of maple, basswood, and hickory, attested to the richness of this woods. The calls of warblers, vireos, and a jumble of other birds floated out over the Mississippi River, which shone like a beacon on the migratory highway. The place was brilliantly, vibrantly, alive.

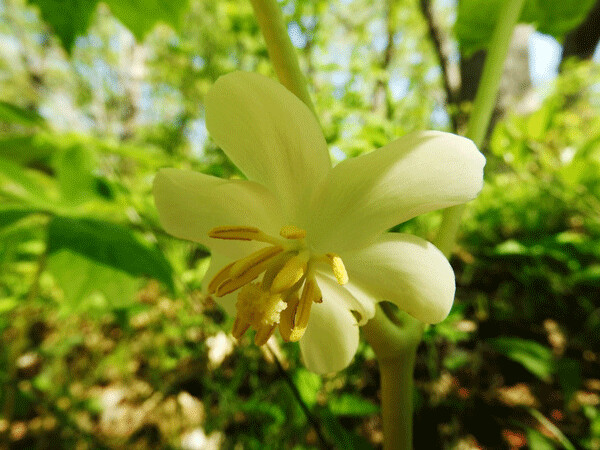

A patch of large jack-in-the-pulpit leaves caught my attention, and I stopped to capture a photo. These unusual flowers don’t have colorful, silky petals and a sweet smell like the others I’d examined that day. They aren’t crafted to attract bees (the pollinators at the forefront of my mind lately); they summon less flashy insects to do their pollen transport.

The outer part of the flower looks like a narrow pouch with a graceful rain awning, or an old fashioned church pulpit. Often the pulpits—known to botanists as the spathe—are green with purplish-brown stripes. This combination of colors, along with a mushroom-like odor, attracts fungus gnats. I wrote about these tiny cousins of mosquitoes a couple years ago when they swarmed my window screens in the fall. There are many species, and some must like to climb down inside the stinky, striped, spathe of an odd flower.

Inside the spathe lives the preacher Jack. His part is played by the spadix—the spike that pokes up out of the pulpit structure. At the base of the spadix are tiny flowers, protected from rain by the curving hood of the spathe. Jack-in-the-pulpits must be at least three years old before they have enough energy to produce anything except leaves. In poorer soils it may take longer. After mustering enough resources and storing them in an underground corm, the plant begins to create male (staminate) flowers.

Similar to the slippery trap of a pitcher plant leaf, gnats tend to be lured down inside the jack-in-the-pulpit flower and then struggle to climb back out on the slick sides. Scurrying around the bottom in a panic, they pick up pollen from the flowers at the base of the spadix, and finally exit through a tiny escape hatch, carrying the pollen with them.

Jack-in-the-pulpits require cross pollination for seeds to form, so the plant hopes that the little fungus gnat will fall into a pulpit with female flowers next. Scurrying around in panic once again, the gnat transfers the pollen to the stigmas on the female flowers. There isn’t an escape hatch in these jack-in-the-pulpits, though, and the gnats generally meet their demise in this beautiful, stained glass tomb. If they’ve done their job (in the plant’s view, at least), a cluster of green berries will be ripen to red by late summer.

What fascinates me about Jack is his transition over time. Young jack-in-the-pulpits with few stored resources are male, with staminate flowers. They only have enough energy to produce pollen. Over time, with ample nutrition, the plant increases in size both above and below ground. Female (carpellate) flowers start to appear on the spadix below the staminate flowers. Over the course of several years, as long as it continues to accumulate enough resources, more and more carpellate flowers appear until the plant is entirely female. If soil is poor or the habitat otherwise unfavorable, then the plant may control its resources output by continuing to produce only staminate flowers, and thus avoid the expense of growing berries.

Another bumble bee buzzed by as I finished taking my photos of this curious plant. Lately I’ve been focused on bees and the flashy flowers they pollinate. Jack-in-the-pulpits are a good reminder that everyone’s journey is different. They choose fungus over fragrance. They don’t need bees or bright colors. Their pollinators aren’t charismatic, but they do the trick. Their gender can change over time. These differences are a good thing. Even though they are neither sweet nor buzzing, jack-in-the-pulpits are a fascinating citizen of these woods.

Special Note: Emily’s book, Natural Connections: Exploring Northwoods Nature through Science and Your Senses is here! Order your copy at http://cablemuseum.org/natural-connections-book/.

For 50 years, the Cable Natural History Museum has served to connect you to the Northwoods. Come visit us in Cable, WI! Our new exhibit: “Bee Amazed!” is open.

| Tweet |