News & Articles

Browse all content by date.

Kanye West, the legendary rap artist, provoked controversy this week when he said in an interview with the celebrity news website TMZ: “When you hear about slavery for 400 years. ... That sounds like a choice.” West was immediately challenged by a TMZ producer, Van Lathan, who said: “While you are making music and being an artist ... the rest of us in society have to deal with these threats to our lives. We have to deal with the marginalization that has come from the 400 years of slavery that you said, for our people, was a choice.” Another rebuttal followed later on TMZ, from prominent Black Lives Matter activist DeRay Mckesson, who advised West, “You need some time to reflect and learn more before you start making public statements.”

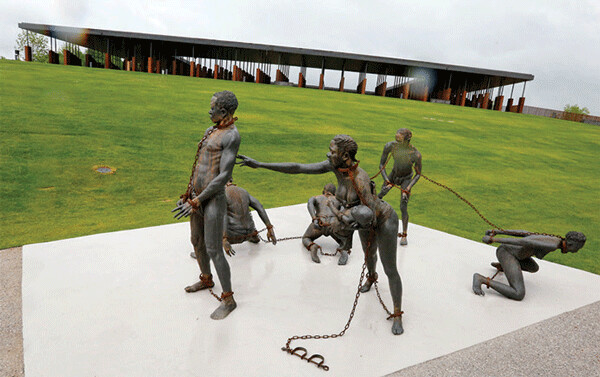

There is a space in the heart of Alabama that might be just the place for Kanye West to reflect on slavery: the newly opened National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery. The six-acre site is a sweeping, solemn commemoration of the horrors of slavery and lynching in America. A large, covered, open-walled pavilion at the center of the memorial has hundreds of steel monoliths suspended from the ceiling, each one marking a county where one or more lynchings happened, with the names of those lynched.

The memorial is the work of Bryan Stevenson and his Montgomery-based nonprofit Equal Justice Initiative. He is an attorney who has represented death row prisoners in the Deep South for decades. In 2015, EJI published a comprehensive report on the history of lynching in the United States, documenting over 4,400 victims between 1877 and 1950.

Stevenson hopes the memorial, along with EJI’s new museum in downtown Montgomery, The Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration, will challenge what he calls the “narrative of racial difference that we have in America, this history of racial inequality that has made us tolerant of bigotry and discrimination.”

“About 10 years ago, we began working on a project to change the narrative. We started doing this research on slavery, on lynching, on segregation. We put out these reports. We started putting up public markers, because ... the landscape is littered with the iconography of the Confederacy,” Stevenson said on the “Democracy Now!” news hour. “For me ... talking about our history of racial inequality is critical to creating a consciousness that will allow us to move forward toward justice and equality. I don’t think we’ve done a very good job of that in our country.”

The memorial and the museum have already sparked serious reflection at Alabama’s capital city newspaper, the Montgomery Advertiser, founded in 1829. A deeply reported section of the paper, “Legacy of lynchings: America’s shameful history of racial terror,” includes articles detailing the paper’s own failings in its reporting on lynchings. Any stories, reporter Brian Lyman wrote, “were undercut by the Advertiser’s unfailing assumption that lynching victims were guilty of a crime, whatever the facts may have been. Those assumptions were often grounded in racist views of African-Americans.”

The paper’s editorial board opened its piece with the sentence, “We were wrong,” and continued, “We went along with the 19th- and early 20th-century lies that African-Americans were inferior. We propagated a world view rooted in racism and the sickening myth of racial superiority.”

While the memorial and museum focus on the past, on 400 years of racism against Africans and African-Americans, Stevenson is focused on the present as well: “We have a schoolhouse-to-jailhouse pipeline. We have jails and prisons that are filled with folks who are not a threat to public safety. We have black and brown people being menaced and targeted by the police. We have a network of political discussions that always exclude people of color. And until we confront those spaces and challenge those places, we’re not going to be able to achieve the kind of justice that most of us seek. That’s my challenge. That’s my heart.”

On an interior wall at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, a pledge is etched:

“For the hanged and beaten,

For the shot, drowned and burned,

For the tortured, tormented, and

terrorized

For those abandoned by the rule of law,

We will remember”

In 2005, Kanye West rocked the country and the White House with seven simple words uttered on a major global telecast to raise money for victims of Hurricane Katrina: “George Bush doesn’t care about black people.” Recently, Kanye West shocked many by professing admiration for President Donald Trump and now saying slavery was “a choice.” Kanye should pay a visit to the memorial in Montgomery, and take the president with him.

| Tweet |