News & Articles

Browse all content by date.

Korii Northrup was in a bar Hurley, Wisconsin when she was drugged. She has no memory of who drugged her or how it happened, but she woke up seven hours later tied to a bed in a basement.

She was able to slip loose of the ropes and climb through a small window, then run through the woods to another house where she found help. She was in Shawano, 180 miles from Hurley.

“A lot of that afterward is a blur,” she said.

This happened in 2007, but it wasn’t the first or last time she was drugged and assaulted. Several years later, “the last thing I remember was being at a bar in Hurley, and then the next thing I remember is, it’s nine hours later and I’m in Eagle River with these dudes. I don’t think they were legit sex traffickers or anything like that. I think there were just a couple of dudes who drugged a girl and took her wherever.”

“I started kicking and punching, like the windshield and the guy and the other guy, and the guy was trying to choke me, and so finally he stopped the car ‘cause I was just struggling and whatnot, and then I got out of the car and it was like 50 below and I was at a gas station.

“I was so confused I couldn’t see straight, people were trying to talk to me, I didn’t know where I was or what was happening. So they called the police and brought me to the police station, and I called my friend and he came and got me.”

Now back in Minnesota, surrounded by family and friends, she has only recently summoned the strength to talk about her experiences. She told her story to the Reader Feb. 23.

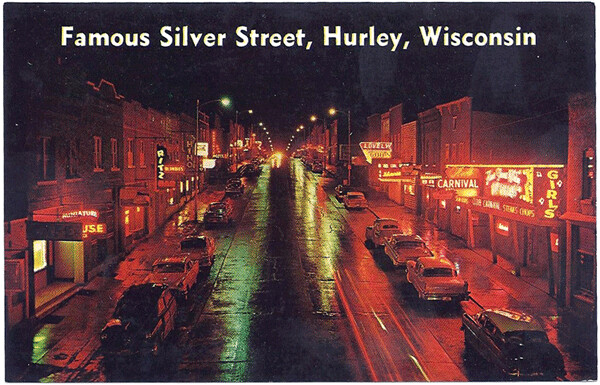

Hurley and its saloon district, Silver Street, has been infamous since the logging and mining boom of the late 1800s. The Milwaukee Journal ran articles in 1886 with titles like “Hurley’s Disreputable Resorts” and “The Hurley Den: A Chicago Girl Tells Her Experience in Court.”

The unsolved 1890 axe murder in Hurley of showgirl Lotta Morgan was the basis of a 1935 novel by Edna Ferber, and subsequent film, “Come and Get It.” During Prohibition bars operated openly along with gambling and prostitution. National Geographic featured the city in 2015 on its show “The Big Picture with Kal Penn,” calling it “the true exotic dance capital of the United States” with one strip club for every 260 residents.

Northrup worked one winter as a dancer and other times as a cocktail waitress. “When you’re a dancer, you never tell people what you’re real name is,” she said. “Lot of people are real secretive because of the nature of it all, they don’t want their family to know, that they’re addicts, or scared of their pimp, or whatever it is they make you do to want to comply or do. Whatever it is, they’re going to hurt your family. I’ve seen countless, nameless people go through those places. I’ve seen dudes taking women out by their hair.”

The two times she was abducted from bars, she was a customer. “I was taught not to speak of my sexual assault,” she said. “You wake up across town sometimes, it’s a matter of, what are you going to do about it? I would explain the whole thing (to police) and they would seem like they’re on board, but then when it came time to prosecute these people, it never happened. They wouldn’t even charge people.

“I stopped reporting because it wasn’t even worth it. Do you know how stressful it is to have a rape kit put on you? Your body becomes a crime scene, it’s not yours anymore. They take everything, they take your fingernails. I feel more traumatized sometimes as a result of what they do afterward than the actual act. So I just gave up. The police aren’t going to protect my body, then it must be a free-for-all.”

Her advice to women of any status: “If you’re gonna go out, go out in a group. Always have your drink with you where you can see it. Even leaving it on the bar is too much sometimes because he’s leaning in. You never know.

“You know who the pimp is. Usually he has two or three girls that he brings up there, frequently he’ll have them working different establishments. Not with the big hat and the fur and the cane, they look like any run-of-the-mill gangbanger and the only reason you know he’s the pimp is, she’s buying his drinks. Usually on her tab. And that’s how they get them into the routine of having to work is, they start you on a tab and you got to pay the tab.”

Her childhood was troubled, but being in trouble taught her the skill that got her out of the basement. “I got out of handcuffs all the time, I’m like Houdini. I was raised by the system. It involved a lot of restraints. I had 82 different placements. I try not to look at myself as a throwaway person, society looks at me as a throwaway person.”

Once labelled as a throwaway, she found it hard to be anything else. “Getting out of the lifestyle is super, super hard, but you’re worth it. You have to wake up in the morning and be like, I am somebody. Even if these people want to make me nobody, I am somebody.

“It’s like a personal determination inside yourself that you’re worth something, because when you live on the fringes of society, you have no worth in your own life. I think that’s the big difference, was that I found worth in my life and who I am. I’m reclaiming who I am because people don’t want me to be Anishinaabe, but it’s not their choice. And so, living in white society my whole life, they’ve always tried to force me to be a white person, or deny me my Anishinaabe.”

She finally returned to Minnesota when her older brother, who had not seen her in seven years, happened to be driving in Wisconsin and saw her on a street corner. He pulled over and said, “What are you doing here?”

“It’s so important to have that thing like, you are worth not having to live that way,” she said. “As many times as you can rescue someone from that lifestyle, until they make that change in themselves, it’s not gonna matter. It’s like an addict, it’s the only way they know how to live, they got to be taught a new way to live. They gotta be taught their life is worth a new way to live, a different path. But I’m Anishinaabe and that helped me because I know what way to live now. I know that I’m worth something and what my role in my community and my family is, and finding that role is probably the most important.”

Doing volunteer work helped her stay on track. “I just started by volunteering for anything that went on. That was first step I took to building self-worth. It was when I did a good job as a volunteer, and then I could take pride in my work. I helped have a fundraiser, I helped organize an event, I helped teach people language, I helped my elders by taking notes for their meetings, being small about it.

“People think life skills are all just learning jobs and stuff like that, but it’s all about learning self and what self is capable of. Little kids do that through play, but as adult, when you have to relearn that. The best way is through volunteering because then, your car payment’s not riding on it, your life isn’t riding on it if you do fail, because you’re a volunteer. If you fail, you got a huge support group of caring individuals who are there to help you find your role.

“It’s just different people, being in a different situation, doing different things. The definition of insanity is repeating the same things and expecting different results. And all you have to is change one thing to not be crazy.”

Victims of trafficking may contact PAVSA (Program for Aid to Victims of Sexual Assault) at 218-726-1931. More resources can be found at enditduluth.org or befreewisconsin.com.

Stuck in Traffick

By Korii Northrup

Buzzed, Bar, Birthday

Woke with a start

bound to the bed,

haphazardly

Silently struggling against ligature

freedom just a misstep away

searching for clothes

escape

Squeeze through the tiny window

running in no direction

desperate for options

Through the woods

a house

Silent squads

rescue

Body a crime scene

fearful tears,

pure panic

Evidence collected ...

Indigenous justice blind

should have stayed silent

stigma unshaken

perp

privileged prosecution

Never charged

her blame

sold into slavery

desecrated

soul wounded

Escaped hell to relive the

nightmare

heart of a warrior

committed to survive

driven to thrive

| Tweet |