News & Articles

Browse all content by date.

Three times a year I get to spend a few days at the elementary school in Drummond, WI, teaching kids my favorite nature facts using my favorite nature props. Once each season, in Fall, Winter, and Spring, I load seven plastic tubs filled with skulls, furs, bones, rubber scat and other oddities into the Museum’s mini-van for a visit to each classroom in grades pre-k through six.

The pre-k kids in Ms. Bonney’s class are one of my favorite visits. Their enthusiasm is too ripe to be contained within tiny, squirming bodies, and their endless stories wander all over the map. We point to our eyes, ears, nose, tongue, and fingers, and practice exploring nature with our senses.

In one of the small, cloth, “touch bags” are a pair of short-tailed weasel skins. It’s fun to watch their little faces light up in pleasure when they touch the soft furs. It’s even more fun to demonstrate why the weasels—both the brown summer fur and the white winter fur—have black tips on their tails. “Imagine you’re a hungry red-tailed hawk,” I instruct them, “and you’re watching this weasel run across the snow. What part of him would you see first and try to grab?” The black tip of course. But the bony talons of a hawk can’t grasp the tip of a weasel tail, so the sneaky critter runs off to safety.

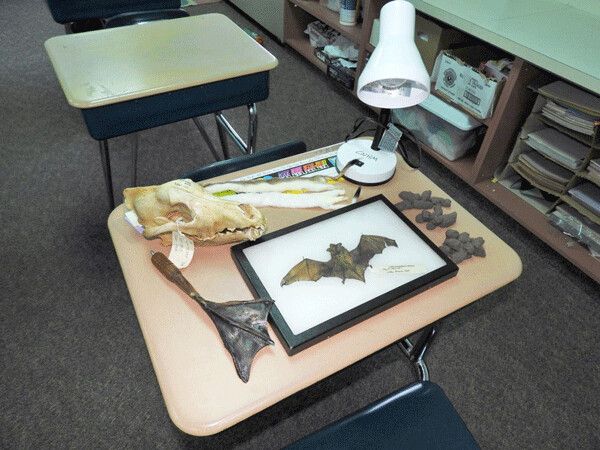

The first thing I pull out of the first grade tub is a dried specimen of a little brown bat. Projected up on the white board through a document camera, its larger-than-life details capture the children’s attention right away. Their favorite part? The fact that you can match your own fingers to the bones in the bat’s wings, including a tiny, upward pointing thumb. This year I was also gratified at the number of oohs and ahhs I elicited when showing off a delicate bat skeleton cast in resin.

During my fall visit, second graders learned how the eyes and teeth of herbivores, omnivores, and carnivores are adapted to their specific lifestyles. Since herbivores are prey animals, they need eyes located on the sides of their heads to watch for danger in all directions. Predators have forward-facing eyes that give them binocular vision for catching prey. Herbivores have flat teeth for grinding up plants, and the wolf skull is full of sharp teeth for shearing meat off of bones. Omnivores, like us, have both sharp canines and flat molars.

For the winter lesson I take second graders a little farther down the alimentary canal. We use a handy identification key and rubber replicas of animal scat to learn more about herbivores, omnivores, and carnivores. Did you ever think about the fact that most herbivores make small pellets like our familiar deer scat? Or that all carnivores tend to make long, ropy scats due to the presence of hair? Or that omnivores find the average of those two by shaping their scats into long cylinders? This lesson gets lots of laughs, but it’s valuable information for little naturalists just getting their start at animal tracking.

The thick pelts of a wolf, a coyote, and a fox grab the attention of third graders, as does a wolf skull familiar to them from our second grade look at carnivore teeth. With this lesson, we also observe the ridge of bone sticking up along the back of the wolf’s skull. This is where its jaw muscles attach. The bigger the fin, the more muscles, and the stronger the animal’s jaw. Wolves can crack the upper leg bone of an adult elk.

Fourth graders migrate on to talk about birds. In the fall, we dress up a kid with all the adaptations of an owl and then dissect owl pellets. In the winter, we compare the adaptations of owls and loons. It is amazing how different two birds can be. Looking at talons vs webbed feet really drives home the concept of being adapted to your specific habitat and lifestyle. A loon could never perch on a tree branch, and an owl couldn’t swim very far. We end the lesson by listening to the territorial yodels of male loons and matching them with sonograms. Of course, I also want to connect the loon calls to owl hoots. Luckily, the fourth grade teacher, Mrs. Thurn, was once the Education Director at the Cable Natural History Museum. She has the best imitation barred owl call I’ve ever heard, and right on cue she’ll give us a perfect “who cooks for you?”

We take a break from life science in fifth grade, and the kids compare the electricity use and heat output of three types of lightbulbs. Once we’ve done the math to figure out how much more expensive it is to use incandescent bulbs over compact fluorescent bulbs—and especially over LED lightbulbs, I have the kids tell me what they’d rather do with that money. Video games I’ve never heard of generally top the list.

With the sixth graders, I get to do a wonderful progression of lessons about symbiotic relationships—one of my favorite topics. Every autumn I gather a couple gallon bags of goldenrod galls and tuck them in the back of a freezer. The kids get pry open galls to see who’s living inside. Mostly they find the gall fly larva who created the gall, but occasionally they discover the larva of a parasitic wasp or a predatory beetle. Some galls are empty—with a telltale woodpecker hole in the side.

I’ve been teaching these MuseumMobile lessons at Drummond since the sixth graders were in kindergarten. By now the kids are accustomed to my tubs of animal parts and my unbridled enthusiasm for weird stuff. The most common behavioral problem I deal with is kids interrupting class with random nature facts and nature stories they just can’t wait to share with me.

Over the years, this part of my job has shrunk as other responsibilities have grown, but I just can’t bring myself to give it up completely. After all, I never grew out of the stage where I blurt out cool nature stories to anyone who will listen!

Special Note: Columnist Emily Stone is publishing a second book of her Natural Connections articles as a fundraiser for youth programming at the Cable Natural History Museum. Since kids in the community are often the inspiration for her articles, the Museum is conducting an art contest for kids to illustrate each chapter with a black-and-white line drawing. Find out more at http://cablemuseum.org/connect/.

For 50 years, the Cable Natural History Museum has served to connect you to the Northwoods. Come visit us in Cable, WI! Our new exhibit: “Better Together--Celebrating a Natural Community” is now open!

| Tweet |