News & Articles

Browse all content by date.

Duluth’s first tourism tax was established on March 17, 1969, by a vote of the city council. The new tax attached a three percent surcharge to hotel and motel rooms in the city. Two-thirds of the proceeds were intended to assist with the operations of the Arena-Auditorium (today’s DECC) and one-third was to be used to promote the city as a tourism destination. A small amount was also earmarked for the city’s general fund, to help the city with tourism-related expenses. Though some motel owners opposed the new tax, it was overwhelmingly supported by the big hotel operators in town, as well as the Chamber of Commerce and the city administration.

The Spirit Mountain Recreation Area opened for business in 1973, and soon experienced cash-flow problems, a trend that continues today. In 1977, the city enacted two new tourism taxes—a one percent food-and-beverage tax on restaurants and bars, and an additional one percent hotel-motel tax—to help with expenses at Spirit Mountain. The DECC also received a portion of the new taxes, as did the Duluth Convention and Visitors Bureau and the Depot.

In 1980, the city added another one percent lodging tax, to be spent on more tourism projects, promotion, and debt. In 1990, they added another one percent.

In 1999, Mayor Gary Doty signed another 0.5 percent food-and-beverage tax into law. Originally intended to finance a DECC expansion, much of the proceeds of this tax were later slurped up by the Great Lakes Aquarium when that fine establishment began requiring bailouts in 2002. Doty’s tax sunset in 2012, when the bonds were paid off. (These were not the only bonds committed to the aquarium by the city, but they were the only ones backed by the tourism tax.)

In 2008, voters were asked if they wanted to approve another 0.75 percent food-and-beverage tax to help finance a new hockey arena at the DECC. Voters said they did.

In 2014, Mayor Don Ness established two new tourism taxes: another 0.5 percent tax on hotel rooms and another 0.5 percent tax on restaurants and bars. Their purpose is to raise $18 million designated for recreation projects in the St. Louis River Corridor. When the $18 million cap is reached, these taxes are scheduled to sunset.

Today, in total, five separate lodging taxes boost the price of a hotel room in Duluth by 6.5 percent, and three food-and-beverage taxes add 2.25 percent to restaurant meals and bar tabs, not to mention deli purchases, food truck specials, street dance drinks, and your favorite door-delivered chicken wings from Domino’s Pizza. In 2018, the eight tourism taxes are projected to raise a total of $11,523,200.

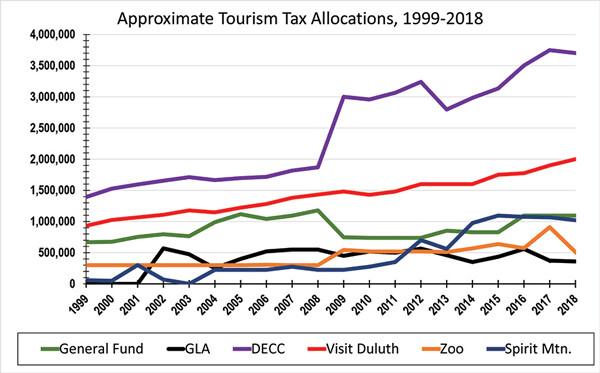

Graphically speaking…

Looking at the graph, it’s apparent that the two biggest recipients of tourism tax are the DECC and Visit Duluth. This makes sense, as both entities are legislatively entitled to a certain portion each year. The graph’s most dramatic feature is the DECC’s big leap upward from 2008 to 2009. That signifies the new 0.75 percent food-and-beverage tax kicking in to pay for AMSOIL Arena.

Since the first days of the tourism tax, the city’s promotional duties have been carried out by a private nonprofit organization that was originally called the Duluth Convention and Visitors Bureau, and today is known as Visit Duluth. Though most of their funding comes from the tourism tax, Visit Duluth is not itself a part of city government. Every three years, the city and Visit Duluth negotiate a contract for Visit Duluth’s services. Members of Visit Duluth are fiercely protective of their budget, and have fought off many attempts over the years of others to appropriate part of it. These efforts (combined with a steady increase in tourism taxes overall) have enabled Visit Duluth’s budget to climb steadily upward.

Surprisingly (to me, anyway), tourism tax contributions to the general fund used to be quite substantial. From 1999 to 2008, general fund contributions climbed steadily, increasing at a faster rate than contributions to Visit Duluth or the DECC. In 2009, however, general fund contributions plummeted, from $1,178,300 to $747,300. At the same time, contributions to the zoo sharply increased. The resolution distributing the 2009 taxes states, “The allocation to the Lake Superior Zoo reflects the new funding proposal for the zoo operations which was offset by a reduction in the transfer to the general fund.”

This is when the city, facing a severe budget shortfall, stopped running the zoo with city employees and contracted with the Lake Superior Zoological Society to run it, to avoid paying union labor costs. As part of that agreement, the city promised to contribute about half a million dollars of tourism tax each year to the zoo’s operation. (As the zoo’s unexpected $910,000 ask in 2017 shows us, of course, half a million may not be enough.)

The zoo is not the only attraction to impact the general fund over the years. The statement of purpose for the 2003 tourism tax distribution states: “A new allocation of $225,000 is proposed to cover operating shortfalls at the Great Lakes Aquarium…The transfer to General Fund was decreased to cover the Aquarium allocation.” Thus, while Visit Duluth’s budget bobs ever higher, the general fund takes all the hits. Considering that Visit Duluth was a big booster of many of the projects that now require propping up, it seems a little unfair.

Since 2009, contributions to the general fund have been slowly and painfully climbing back up, but they have still not returned to their 2008 level. The tourism industry itself has grown considerably during that time, and the city’s tourism-related expenses have grown along with it. The general fund could easily stand to be reimbursed another million or so each year. I’m sure Visit Duluth would be happy to contribute to the cause.

As for Spirit Mountain, it’s interesting to note that tourism tax contributions to the ski hill (which cover lease payments on the Adventure Park, bond payments for the Grand Avenue Chalet, bond payments for the water line, operational subsidies, and special projects) have come in at more than a million dollars a year for the past four years (2014 barely squeaked under the wire, at $975,700). If that’s a plateau, it’s a high one. Let’s just hope it’s not a stepping stone to higher altitudes.

A note on the graph

As the title says, this graph is approximate. I drew much of the information from tourism tax distribution tables, which are estimates made by the city and approved by the city council each year. Sometimes the amount of tourism tax an entity was receiving was clear and sometimes it wasn’t. For example, a given year’s table might show that a lump sum of tourism tax was designated for “Debt Service,” but not specify how much of that money went to the DECC, how much to Spirit Mountain, how much to the zoo, and so on. In those cases, I estimated bond payments. Anyone wishing more detail on where I got my numbers is welcome to contact me care of the Reader.

“One other thing” in Chisholm

Nothing marked the Chisholm City Council meeting of December 13, 2017, as special. Mayor Todd Scaia and the council listened to reports from city staff, handled housekeeping items, offered their congratulations to city Building Safety Official Steve Erickson, who was retiring after many years of service, broke into executive session to discuss ongoing litigation with Ironbound Studios, and scheduled future meetings. As councilors prepared to adjourn, Mayor Scaia indicated that he had one more thing to say.

Todd Scaia: Council, one other thing…I do have an announcement that I’d like to make. Dear citizens, city employees, and fellow councilors, after much thought and deliberation I’ll be stepping down as mayor, effective January 2, 2018. I have served the city of Chisholm since 2003. In the last six years, I have served as part of the city council. My time on the council has been challenging, difficult, and educational. I have learned that being a leader of this city does not change who you are, but reveals who you are. In order for me to bring real change to this community, I must first make changes in myself for my children and my family. There are a lot of different ways to make a contribution and changes to the city of Chisholm. A common mistake people make is to think that being a leader is the only way to make a difference or be involved. I plan to reflect on my time on the city council and utilize my strengths in other ways to make Chisholm a stronger community. My resignation will also give someone else an opportunity to serve the city, as there will be four offices up for election in 2018. Council President Rahja has done a fantastic job filling in and will do so in the future. A lot of good work has been accomplished. A lot of challenges lie ahead. I wish this council and the future councils nothing but continued success.

Following the meeting, Scaia had little further to say to reporters. In an email to one local TV station, he said he was resigning for health reasons.

Well, that was a shocker. Scaia has only been mayor for a year, having moved into the position from the city council when former Mayor Mike Jugovich was elected to the County Commission. The most notable event to happen during Scaia’s tenure was the strange resignation of City Administrator Katie Bobich, who quit abruptly after only eight months on the job, citing mysterious “circumstances.” When I visited Chisholm and pressed Mayor Scaia on the matter in September, he threatened to call the police on me. Now he was quitting. Hmmm.

It was kind of a teaser statement, too. What did the mayor mean when he said he had to “make changes in myself for my children and my family”? It sounded like he was trying to make up for something bad, but what was it? Did it have anything to do with Katie Bobich?

| Tweet |