News & Articles

Browse all content by date.

Over the past two days, I revised a previous Duty to Warn column about copper mining titled “Corporate Sociopaths Out of Northern Minnesota” and then I also revised another column about the infamous British/Australian copper mining giant Rio Tinto that has devastated so much of the earth. Rio Tinto, the corporation, was named after the Spanish river (“red river”) that was discolored because of previous underground copper mining pollution that released iron oxide (rust) into the river. The company began its worldwide operations in the part of southwestern Spain that has been mined for copper and other metals ever since the Roman Empire started exploiting the area for copper, gold and silver. I titled that column “Rio Tinto, Still Polluting After All These Years”.

But then I decided to use as a central piece, the following short Guardian story about the Chilean trans-national mining company Antofagasta. Antofagasta is the major mining company that now owns (and up until recently has been fronted by) Twin Metals in the process of obtaining permits for mining. I do intend to submit these two revised pieces to some of the internet websites that usually re-publish my Duty to Warn columns (see below).

Antofagasta has plans for a large underground mine (the “Twin Metals proposal”) where low-grade copper/nickel ore has been found close to the Boundary Waters Canoe Area (BWCA), a federally-protected wilderness area that is contiguous with Canada’s Quetico Provincial Park.

Antofagasta has a reputation of being anti-union, anti-worker and anti-environment and has exhibited such behaviors wherever they have decided to exploit low-grade copper sulfide ore anywhere in the world. The owner/operator of the proposed Twin Metals underground copper mine was deeply involved in the September 11, 1973 bloody military coup led by General Augusto Pinochet which deposed the democratically-elected Socialist Party President Salvador Allende who was against the power of corporations that were exploiting the land and displacing people from their homes. (Recall that the US had been involved in trying to prevent Allende’s election in 1970 and – after Allende was actually elected - made plans for “regime change”. Those plans were orchestrated by Henry Kissinger and President Richard Nixon with the help of Richard Helms of the CIA. (For more details on the plot, google “Salvador Allende and Henry Kissinger” or click on http://nsarchive.gwu.edu/NSAEBB/NSAEBB437/)

At any rate, the following short article should make even the most ardent supporters of any and all kinds of mining in our water-rich state wonder how firm should be their advocacy for allowing trans-national mining companies to do whatever they want to after they obtain the necessary permits. Transnational corporations meet the definition of sociopathic entities and therefore can be expected to close off their newly-privatized property to inspection and also close off the toxic tailings lagoons to observers. Armed guards will probably be employed to enforce their new policies.

NOTE: My original 2014 column “Corporate Sociopaths Out of Northern Minnesota” article may be accessed at http://www.salem-news.com/articles/march042014/mining-corporations-gk.php and my 2016 Rio Tinto article may be accessed at https://www.transcend.org/tms/2016/07/duty-to-warn-rio-tinto-the-river-the-mine-and-the-corporation-still-polluting-after-all-these-years-5000-years-later-that-is/. Those sites have several good photos attached.

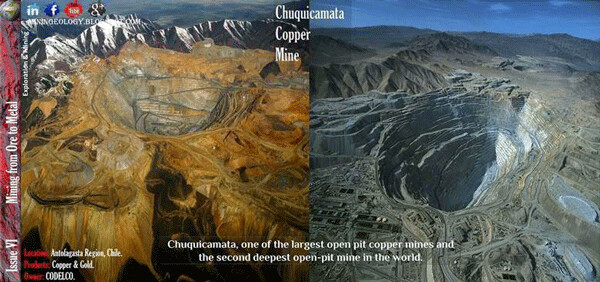

Below are photos of an Antofagasta mine in Chile that shows the total devastation of the surrounding environment – which always happens with modern sulfide mining techniques. No photos of Antofagasta tailings pits were available on the internet, but all sulfide mines are necessarily accompanied by permanently toxic tailings ponds or lagoons, that are the final repository for the finely ground-up mine slurry that, when exposed to air and water, forms deadly sulfuric acid plus a toxic brew of heavy metals.

When such sulfide mine slurry is pumped to a pit or pond that will contain water, a highly acidic pH of 2 be achieved (approaching the acidity of stomach acid) which is incompatible with any form of life and will chemically burn any living tissue, including the beaks, gullets and webbed feet of any water bird that thinks it is landing on a lake. (Note: a neutral pH is 7.0 and the most highly alkaline pH is 14.0, which is also incompatible with life.) But the toxicity of the tailings of copper and nickel mining isn’t confined to the highly acidic pH. The lethality of the tailings also involves other sulfide ore-related heavy metals, such as Lead, Arsenic, Nickel, Zinc, Cadmium, Vanadium, Antimony, Manganese and Mercury.

Read on and re-think any reflexive support you might have about copper/nickel sulfide mining in our relatively pristine northern Minnesota where there are – at present - no toxic copper tailings ponds (like the one at Mount Polley, British Columbia where, in 2014, the earthen dam holding back tens of millions of cubic meters of toxic tailings breached the dam and instantly destroyed streams, lakes and rivers downstream). It doesn’t take much of an imagination to see that any such release from any tailings pond up north can do the same thing to the St Louis River estuary and Lake Superior. (Access my 2017 article on the Mt Polley environmental disaster is at http://www.globalresearch.ca/environmental-disaster-the-polymet-mining-project-and-the-lethal-impacts-to-the-st-louis-river-watershed-and-lake-superior/5572146.

A birds-eye view of the mouth of the tiny (normally about 6 feet wide) Hazeltine Creek (now 120-150 feet wide) as it enters into Quesnel Lake, the previously deepest, purest lake in British Columbia and a famous trout and salmon fishery; that is, until August 5, 2014, when 24,000,000 cubic meters of toxic water and sludge breached the Mt Polley mine’s tailings dam and exploded downstream. The tan material in the photo represents millions of floating dead trees that were swept away in the massive sludge flood.

What’s left of the Mount Polley tailings pond after the breach

Chilean Dam Can't Hold Back the Hatred

By Jonathan Franklin - Caimanes, Chile

Friday 21 March 2014

https://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/chile-los-pelambres-copper-mine-antofagasta-broken-town

Residents say the dam linked to the (Antofagasta) Los Pelambres copper mine “created so much inequality that it broke the town”

"It is a vicious circle with the big companies ... They take the water and divide the small community. They do this all over the world, it's not just here … when the mining company leaves, that huge tailings pit will stay and will still contaminate water. It's not dry. It's filled with water and that increases the chance of more water contamination.”

Antofagasta open pit copper mine, Chile

Visitors to the small Chilean village of Los Caimanes are greeted by a row of black flags and graffiti marking opposition to a huge $600,000,000 dam built in the Andean foothills above town. The opponents of the dam are called "Las Banderas Negras" (the Black Flags) and dozens of homes have the flags and hand-printed signs in their front yards, with messages exhorting Antofagasta Minerals, a wholly-owned subsidiary of Antofagasta plc, a mining company trading on the London Stock Exchange, to leave the town alone.

Supporters of the mine, many of whom have received tens of thousands of dollars in community grants from Antofagasta Minerals, have seen their windows shattered. A car was burned and when the mining company bought the locals an ambulance, someone immediately smashed the windows.

Fights against El Mauro dam – named after the submerged ranch of the same name – have been going on for nearly a decade, and though opponents and proponents are no closer to agreement, they all concur on one thing: the construction of the dam has shattered the peace of a rural mountain community.

Sandra Dagnino, a lawyer representing a group of townspeople in a lawsuit against the mining company, said the money has caused "a total rupture of the social fabric. Mothers no longer speak to daughters," she said. "The town has been broken."

"Fights. Pure fights. It divided our town, that's what happened," said Marlene Carvajal, 48, a fourth-generation local, when asked about the legacy of the mine. "They cut off the water," she claimed. "We knew that would happen if they built a dam up by the headwaters."

The dam was built not to hold back a river, but billions of pounds of ground-up rocks and waste from the huge copper mine known as Los Pelambres, which is owned by Antofagasta Minerals. Waste from Los Pelambres is delivered via pipelines that run for dozens of miles through the Andes, delivering crushed rock and slurry to the expanding lake that is designed to keep growing as it absorbs refuse from the copper mine.

Carvajal is among many in town who blame the dam – built across a narrow watering hole high above the town – for the current lack of water. "We used to have pools of fresh water down behind the school. Even when there were seven years of drought, we had the pools."

In response to lack of water – though they deny the dam is responsible and blame the seven-year drought – Antofagasta Minerals has drilled four wells and will soon provide townsfolk with water from the underground aquifer. For now, water is provided by tanker trucks that haul water up from Los Vilos, a coastal city some 30 miles away. "I bring about 60,000 litres a day," said Franklin Martinez as he pumped water into a holding tank on a hill above town. "It used to be two loads a day, now it is four."

"It is a vicious circle with the big companies," said Carvajal. "They take the water and divide the small community. They do this all over the world, it's not just here … when the mining company leaves, that huge tailings pit will stay and will still contaminate water. It's not dry. It's filled with water and that increases the chance of more water contamination.

A statement provided to the Guardian by the mine's owners say the mine "does not exhibit characteristics that permit it to be defined as toxic", adding that the dam holds a reservoir of non-essential material called a "tailings pit".

Environmental activists have a different description – they call it "the biggest toxic waste dump in Latin America" and fear that in heavy rains or a large earthquake the wall of sand could collapse, thus unleashing a sea of sludge that would wash away their town.

The environmentalists cite a March 1965 earthquake in the area that measured 7.4 on the Richter scale and which knocked down a smaller tailings pit that led to the town of Copper being swamped. An estimated 150 people died in that tragedy but fewer than 40 bodies were ever found amid the thick mixture of rocks and water. Antofagasta Minerals response to this accusation is that "El Mauro was designed to be capable of supporting 'the maximum believable earthquake' – above 8.0 on the Richter scale".

Given that Chile long held the spot for the largest earthquake ever recorded, 9.5 on the Richter scale during a 1960 quake, many locals worry that the dam could collapse in the event of a huge quake.

The sheer size of the wall of packed sand is part of what terrifies local residents. The retaining wall, now half built, is scheduled to top out at 810ft – about as long as the Titanic if it were stood on end. This wall will hold back a mixture of water and 1.7tn tonnes of ground up rocks from the mine when completed. Despite the miniscule concentrations of metals at the mine – in this case one half of 1% – modern industrial mining is executed on such a massive scale that profits from Los Pelambres totalled $2.2bn during 2012, equivalent to $6.1m a day.

Millions of dollars from the mine have also poured into the town of Caimanes. Using local groups as a key element of their corporate social responsibility plan, Antofagasta Minerals has funded dozens of community projects ranging from small shops to worker training programs. "Let's say you want to open a laundry. You can apply for the money, say 9m pesos [US$18,000]. And they will give it to you … some families had three or four projects like that approved." said Angelo Herrera, a local restaurant administrator, as we drove around town on a makeshift tour. "Even if you never opened the laundry, you had the money. But after that, you were on their side."

Carvajal, who spent years as a community organiser against the mining project, organised bingo nights to raise money for lawyers and even flew to Mexico to lobby against the dam, has now given up. "This town has no future," she said. "We have no water. People are divided. All they [protesters] want is money to leave town, they are not fighting to get their water back but [to get] cash to leave."

Carlos Cortes, a local businessman, disagreed. "Spectacular," he said when asked about the future of Caimanes. "They will pave the road and this will be an alternative route to Santiago [the capital]. But Cortes was clear to add that "we didn't ask for this mine, it was the government [of then president] Ricardo Lagos that made the decision", and it "created so much inequality that it broke the town".

| Tweet |