News & Articles

Browse all content by date.

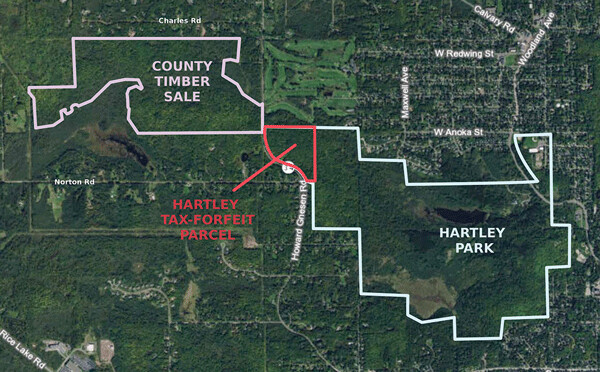

In May, Duluth residents in the area of Norton and Howard Gnesen Roads received a notice from St. Louis County, alerting them of an upcoming timber sale in their neighborhood. The historic wind storm of 2016 had wreaked havoc on certain tax-forfeit parcels managed by the county. They planned to sell the wood to reduce the risk of wildfire and encourage the regeneration of a healthy forest. According to the notice, the county wanted to remove wind-damaged trees and some shorter-lived species like aspen and birch, while leaving other trees alone. “We plan to reserve...as many of the healthy, undamaged maple, basswood and oak trees which can be feasibly retained.”

The notice included a map showing the possible area of timber operations, but it omitted one area on the other side of Howard Gnesen Road: Hartley Park. Most citizens are probably unaware—I certainly was—that 40 acres of Hartley Park is not owned by the city. It’s tax-forfeit property managed by the county. As the county prepares for its timber sale, they are considering adding timber from Hartley Park to the list.

According to Mark Pannkuk, the county’s Area Land Manager (and the sale’s point of contact), the county was initially approached by the Duluth fire department with concerns about the heavy fuel load that was drying out in the Hartley forest. Some of the downed trees had been removed from the east side of the park following the storm, but the west side, including the county’s portion, remained untouched. The fire department hoped a timber sale would help cut the risk of a wildfire. As of press, no final decision about Hartley has been made. Meetings continue to be held among city, county and park staff to decide the issue.

At the property west of Howard Gnesen, the county continues to survey the timber and prepare specifications for its removal. According to Pannkuk, the county will employ various strategies (from clear-cutting to doing nothing), which will be determined by individual site conditions. He added that clear-cutting is the favored method for regenerating aspen, which grow back vigorously in full sunlight.

Salvage tree sales earn the county less money than standing trees because logging crews and equipment have to work harder to extract usable timber from the tangle. According to Pannkuk, the county earns as much as $40 per cord for regular non-salvage trees, while with salvage trees the bidding can start as low as $5. The trees themselves are often still commercially useful. Trees that tipped over but still have roots in the ground continue to leaf out even if they’re horizontal. It is doubtful that they will survive in the long run, but for now they’re fresh.

As planned, the timber harvest will take place this coming winter. The frozen ground and drainages will grant logging equipment access to the forest while minimizing their impact. Pannkuk said that frozen-ground harvests of aspen have “much better success with natural regeneration,” because aspen regenerates from its roots, and roots do not suffer much damage from logging equipment when they’re under frozen ground. Pannkuk mentioned that natural regeneration is planned for the harvest areas, as the county will not be doing any planting

I asked Pannkuk about ash trees, of which there are considerable numbers in the sale area. Last year the rapidly spreading invasive emerald ash borer (EAB) beetle was discovered near Hartley. This means that within a few years all the ash trees in Hartley will be dead. I wondered if the county would focus on harvesting the ash before it died.

Pannkuk did not seem especially concerned. He said that field workers with the Department of Agriculture were testing ash trees in the harvest area for EAB, and that they were considering releasing parasitic wasps on the site. Parasitic wasps were first released in Michigan in 2007, and have shown they can survive, but whether they will have any real effect on the EAB invasion is a question that will take years to answer. For the county’s part, Pannkuk said they hadn’t decided whether to cut the ash or not, as they were more focused on aspen and birch.

Jim Shoberg, a project coordinator with the city, said the city had received some negative publicity last year for removing timber at Hartley after the windstorm, and hoped not to repeat that experience. “We are actively trying to figure out how best to [reduce fuel loads]....Once we do that, we’re going to publicly announce what the plan is, but we’re not quite there yet.”

As for Hartley Park’s peculiar ownership arrangement, Shoberg told me that he, too, had been surprised to find out that part of the park was tax-forfeit land. “We were digging into the titles, and turns out it never got transferred over properly.” Now that they were aware of the situation, Shoberg said, they hoped to work with the county to put the land under city ownership. “They’ve indicated that they’d be willing to talk to us about it.”

Kitty blues

“It just makes me so mad,” Sarah Carlson told me. “It’s not fair! Like, Animal Allies, it’s not your cat!”

I recently wrote about how my family found our lost cat at Animal Allies but were not allowed to have her back because more than five days had elapsed (twelve days had gone by) and somebody else had signed up to adopt her. I described the total refusal of anyone at the organization to consider returning our cat. I described the impenetrable wall of bureaucracy I faced at every level. But Duluth resident Sarah Carlson wasn’t responding to my case. After my article appeared, she contacted the Reader to say that almost exactly the same thing had happened to her.

Carlson told me that in 2015, their family’s 18-year-old cat Pansy had disappeared from their yard. “She was an inside/outside cat,” said Carlson. “She was in the house all the time, all winter. I would let her out in the yard now and then. She loved being outside now and then.” Pansy wasn’t microchipped. Carlson searched the neighborhood and called the city animal pound and Animal Allies for two weeks looking for her, with no luck. “I had given up,” she said. “I thought she died.”

About six weeks later, Carlson saw Pansy featured on a Northland News Center pet adoption segment sponsored by Animal Allies. “They said her name was Lucy, and she was a...domestic shorthair, so sweet and sociable….and I’m like, ‘That’s my cat Pansy!’ And I was crying, and I’m like, ‘She’s alive, so we can get her!’”

Carlson called Animal Allies to let them know that Pansy was hers. Like me, she sent pictures to prove it. She also sent vet records. But it didn’t matter. She was told that Pansy was no longer hers because more than five days had gone by, and somebody else had signed up to adopt her. When she protested that she had called Animal Allies for two weeks looking for Pansy, she was told that she should not have stopped calling. Pansy was going off with another family, and that was all there was to it.

“It was crazy! Horrible!” said Carlson. “Here I lose my cat, and then I figure she’s dead, then I find out she’s alive, then I find out I can’t have her….You know, they were like, ‘The only way you can pursue this is if you want to take it to the courts, but we’re a big organization and that’s really pointless. It’ll cost you a lot of money.’”

“That’s what they told you?” I asked.

“Yes. It’s ridiculous. I felt really bad. I just wanted to go over there and [say], ‘I’m going to take the cat. Sorry.’ And, of course, I was powerless.”

When I asked Carlson who she had spoken with at Animal Allies, she said Executive Director Lindsay Snustad. Ms. Snustad was also the person I had dealt with during my own ordeal.

When I contacted Ms. Snustad for comment on Carlson’s story, she emailed me the following reply:

“In regards to Pansy and all shelter pets, Animal Allies Humane Society maintains a strict confidentiality policy in regards to veterinary patient and adoption records. Animal Allies stands behind our adoption policies and we adhere to all state and local animal welfare laws. The story you have shared with me is not an accurate representation of our standard operating procedures.”

As for Carlson, she hopes Animal Allies revisits their policies. “I think something should change. It’s just so, so wrong.”

| Tweet |