News & Articles

Browse all content by date.

“They exist in some of the most extreme habitats on earth, from the deep sea trenches to mountaintops and Antarctica. So I thought, maybe I could find one in Wisconsin, too!”

Kaylee Faltys, the Museum’s new Curator, sat down with me recently to talk about her hunt for the wondrous water bear.

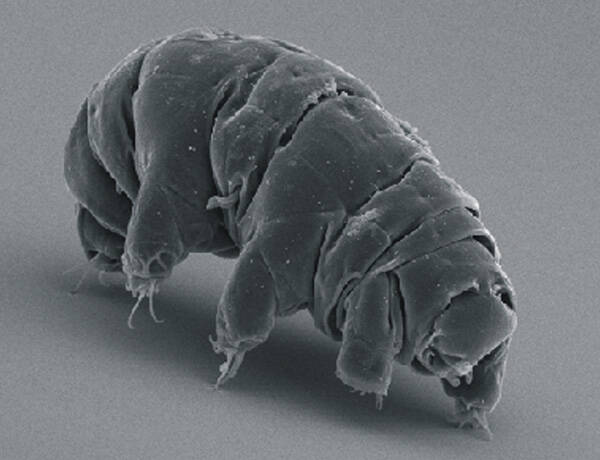

“To know about something for eight years and then finally see it was thrilling!” said Kaylee. She’d first learned about water bears in an aquatic invertebrate ecology class as an undergraduate. Water bears, also known as tardigrades and moss piglets, are aquatic, microscopic, eight-legged animals, and are thought to be the most resilient animal on earth.

“They are the ultimate honey badger!” joked Kaylee, referring to a viral video from 2011 about an African mammal who was named “The World’s Most Fearless Creature” by the Guinness Book of World Records. The catchy tag line from the video was “honey badger don’t care.” While honey badgers don’t care about venomous snakes and stinging bees, water bears don’t care about extreme temperatures, x-ray radiation 1000x the lethal human dose, desiccation, the vacuum of space, and pressures higher than you’d experience in the deepest part of the ocean. Among scientists and naturalists, water bears have developed quite a reputation for being tough.

“They’ve survived in outer space! They seemed too good to be true,” said Kaylee, “so I didn’t think I’d ever see one in real life.” But when Kaylee started researching lichens for the Cable Natural History Museum’s new exhibit, an idea started developing. Lichens are leaf-shaped organisms composed of both fungi and algae that grow prolifically on tree trunks and other surfaces. They provide habitat for a multitude of microscopic life. “Lichens are one of water bears’ classic habitats,” she said, “and I started thinking about how cool it would be to actually try to see one.”

So, armed with her trusty pocket knife and bundled up against subzero temperatures, Kaylee ventured into the untamed wilderness—of the Museum’s backyard. After slicing a small patch of lichen off the tree, she brought it back inside and soaked it in room temperature water overnight. Kaylee hoped that the frozen water bears would come back to life.

Despite their crazy survival skills, water bears aren’t considered “extremophiles.” Those critters actually seek out and thrive in extreme environments like deep sea vents. In contrast, water bears have learned to simply endure. Their strategy involves going into a state of “cryptobiosis” or extreme hibernation. All measureable metabolic processes stop. Their water content can drop to one percent of normal. The organism seems dead, but the condition is reversible.

Getting rid of water is a key to their survival. Water expands and contracts drastically as it freezes and thaws, which can damage cells. If any water molecules are left as a water bear dehydrates, a sturdy sugar called trehalose physically prevents them from rapidly expanding as a result of temperature changes. That’s not all. Flexible, shapeless proteins rearrange themselves into solid biological glass as they dry out. This bioglass wraps other important proteins and molecules in a stiff, protective envelope that holds them together. The bioglass melts as the water bear rehydrates, and everything starts moving again. These adaptations are so effective that water bears have survived more than 30 years in their state of suspended animation called a “tun.”

Back in her office, Kaylee put a little bit of the damp lichen on a microscope slide, covered it with a slip, and started searching around the edges for signs of life. Almost immediately she spotted a little wiggler. Although it was almost completely translucent, its chubby, segmented body, four pairs of stubby legs, and two eye spots were readily visible. “The little guy moved fast,” she exclaimed. “If I looked away he was gone!”

“This is a milestone in my scientific life,” philosophized Kaylee, who just began her dream job as a museum curator after receiving a master’s degree in biological sciences from South Dakota State University. “It made my day.” And now Kaylee is hoping to share her excitement about these amazing, oddly cute little creatures. “I’m planning to hold a Tardigrade Treasure Hunt program this summer, to help people discover the amazing varieties of life that exist out of sight in our own backyards.”

Special Note: Emily’s book, Natural Connections: Exploring Northwoods Nature through Science and Your Senses is here! Order your copy at http://cablemuseum.org/natural-connections-book/. Listen to the podcast at www.cablemusum.org!

For 50 years, the Cable Natural History Museum has served to connect you to the Northwoods. Come visit us in Cable, WI! Our new phenology exhibit: “Nature’s Calendar: Signs of the Seasons” is open through March 11.

| Tweet |