News & Articles

Browse all content by date.

I love a good beer story. This one arrived in my email recently:

“The story of Orval [Trappost Ale] begins around 1070 AD.

“Princess Matilda, a Duchess of Burgundy, was passing through the forest in what is now Belgium with a group of travelers. They stopped to rest near a clear spring, and as Matilda trailed her hand in the water her wedding ring – a memento of her deceased husband – slipped off her finger and quickly sank. Matilda’s heart sank along with the ring, but she fell to her knees and prayed for its return.

“Imagine her delight when a trout swam up to the surface with her gold ring in its mouth, returning it to her! She proclaimed this area to be a “Golden Valley,” and gave the land to the church to establish a monastery. To this day, the trout and ring can be seen in Orval’s logo.

“The first church was consecrated at Notre-Dame d’Orval in 1124, and the monastery became part of the Cistercian (Trappist) order in 1132. Orval was rebuilt after fire in 1252, and rebuilt again after a complete sacking and pillaging in 1637, during the Thirty Years War. But when Napoleon’s General Loison sacked and burned Orval in June 1793 everything was wiped out. The community was disbanded in 1795.

“But in 1926, the rebirth of Orval began – and a brewery was included in the construction plans, as a traditional way of earning revenue for construction and daily operations.

“In the decades since, Orval Trappist Ale has earned global recognition: there is no other beer like it. It’s made from pale and caramel malts, with liquid candi sugar; it’s fermented by the Orval yeast strain, dry-hopped, then bottle-conditioned with Brettanomyces, a yeast that consumes complex sugars. This leads to Orval’s ageworthiness; its dry finish; a bold, acidic sharpness; and a sourness that is somehow soft and appealing.”

This missive was from Craig Hartinger of Merchant du Vin, the great Seattle-area beer importer. What Craig failed to mention is that as long as there has been a monastery, there almost certainly has been a brewery. It wasn’t until the rebirth of the monastery in the late 1920s that a commercial brewery was established in 1931 that employed laypeople from the community. Even though the brewery is not a totally monastic pursuit, it only opens to the public twice a year. This year it’s on Sept. 15 and 16.

The reason for waxing eloquent about Orval? Merchant du Vin was announcing the first-ever Orval Day on March 26. Venues celebrating the day are listed at merchantduvin.com. A portion of proceeds from each bottle of Orval sold on that day will be donated to MAP (Medical Assistance Progams) International (map.org).

That was enough to make me seek out one of the bowling pin-shaped bottles. It had been too long since I’d had one.

It pours with an incredibly rocky white head that looks substantial enough to scale (if you were a half-inch tall).

It comes on bright and tangy in that peculiarly Belgian way. There’s a lot going on with each sip. Zesty complexity.

A few weeks ago I mentioned I was hoping to get my hands on beer from Brewery Vivant of Grand Rapids, Mich. I heard the brewery is in a former funeral home, and as a former live-in funeral home caretaker, I can dig that. I also heard they make tasty beer, and that it is available in Chicagoland.

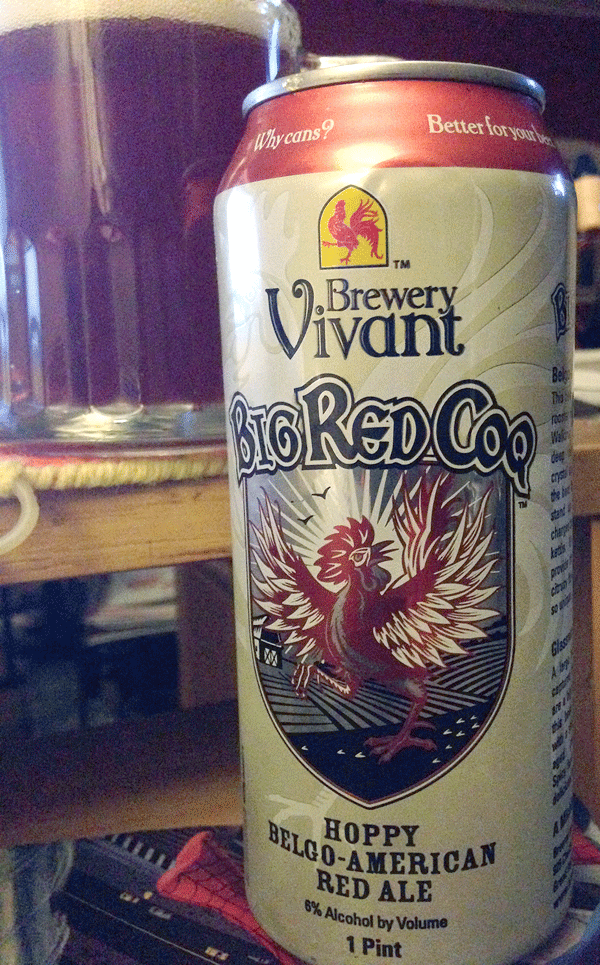

Once again colleague Myles Dannhausen came through, this time with a four-pack of Brewery Vivant’s Big Red Coq, a “Hoppy Belgo-American Red Ale,” as the label on the pint can states.

Why cans? The label asks, and answers

in three lines:

Better for your beer.

Better for your Earth.

Better for your adventure

Adventure? I’m not sure I’m up for that. Can I just sit at my desk and drink it?

Don’t know why my hopes were insanely high for this beer. In my anticipation, I focused on “red” from the main title when I should have focused on the lead word of the subhead – “hoppy.”

A citrusy nose is followed by a big fruity punch in the mouth and a distinct grapefruit finish. I can’t quite put my finger on a specific fruit – even though the label claims a mango flavor (I don’t get mango; lilikoi, maybe).

It’s a drinkable 6 percent ale, but I could go for just a little more depth from the crystal malt, just a little more malty redness to Big Red Coq. It surprises me to say that, having written in the past about the cloying nature of reds, but this beer goes in the opposite direction, elevating hops above the crystal malt that is normally the star of red ales. Instead of the Big Red Coq that is promised, it’s a little red coq.

Hopheads, however, should find it to their liking. Weirdos!

| Tweet |