News & Articles

Browse all content by date.

Spring feels a little bit lethargic this year. Maybe the shortage of human contact contributes to a less spring-like feeling in the air (not that I, as others will attest, shine at sociability). Whatever the source, spring seems less springy. Robins have arrived around Aurora, but sight of them in overcoats isn’t warming.

Could be the number of springs under my belt bring on comparisons. Autumn is the season I usually favor, but for more than a decade spring became special due to maple trees. From blasts of blaze red in autumn, maples reward us with bursts of sugar in spring. Though much diluted, sweetness is in the sap. Most people know this in the same way we know trigonometry; in a book on paper. It takes turning sap into syrup to give a fuller lesson.

Coming from Chicago, the turning of seasons didn’t represent as much change as was the case when my family moved to northern Minnesota. In the urban world change of season was mostly about temperature. In the north seasons had other names and functions. There was partridge season, wild rice, hunting, skiing, along with a sizeable number of other well-known seasons northerners enjoy. Maple syrup season is known but not widely observed. For one thing, doing maple syrup requires a lot of preparation, and a good deal of physical labor all for a very chancy opportunity to come away with a small reward.

As with many pursuits in my life there was near zero chance I’d make a profit. Satisfaction was in breaking even (if lucky) or in not losing too much. Success, however, was in making whatever amount of syrup nature allowed.

One hundred taps was the most I ever worked with. That’s hand drilling 100 holes, putting in 100 spiles, and hanging 100 collectors. Done on flat ground with no snow to sink in it might not have been the struggle coping with knee deep drifts and fallen logs made it into. You can look up what a gallon of water weighs (sap is slightly heavier). Each tree might yield a gallon. Put 4 gallons into each of two 5 gallon pails and you see how much weight and how many trips are needed to gather from all 100. (Unless you’ve got large scale and proper south facing slopes tubing proved more bother than it was worth. What would you do with 200 feet of frozen sap in a tube?)

Like the maple tree itself, sap doesn’t come to you. You have to go to it and take it to your boiler. Big operations use what’s called an arch. Sap goes in one end and syrup out the other. Steady monitoring is needed, and most commercial arches use gas or fuel oil for boiling heat.

To me arch-made syrup is too tame. It’s a commercial product lacking the spirit of small-batch syrup cooked outdoors over a wood fire.

Some of you may recall Elliott Meats from Duluth. One of their former stainless steel tubs holding approx. 400 gallons was the boiler I used. Straight boiling needs less supervision, though arch users claim batch boiling makes cruder syrup. If crude means having more maple taste they’re correct.

Batch boiling you could add the latest run into a cooked down batch. Like aging wine and cooking chili batch cooking adds character not found in sap-in-syrup-out products on store shelves. The way loggers have intimate personal insights about forests, making maple syrup does some of the same.

Maple (and other) sap, you see is really a liquid form of the previous summer’s history. Sap from a lush, wet summer had more mineral that would condense into what is called sand. In a dry year the sap contained elements the tree produced to conserve its moisture. Every boil told a story of past conditions as experienced by a tree.

Nature doesn’t give up its secrets or voice its tales easily. The information has to be worked for and coaxed out. In a good year (at a sap to syrup ratio of 40 to 1) we might make 40 gallons to share and give as gifts. The value of that syrup was in work, what was learned, and what it meant. Can’t be bought off the shelf nor, I think, does true environmental knowledge come in classrooms.

Some things have yet to be reckoned. It’s easy enough to see how early people would have seen squirrels licking up sap dripping from a broken maple twig. Sampling this, they’d find it faintly tasty.

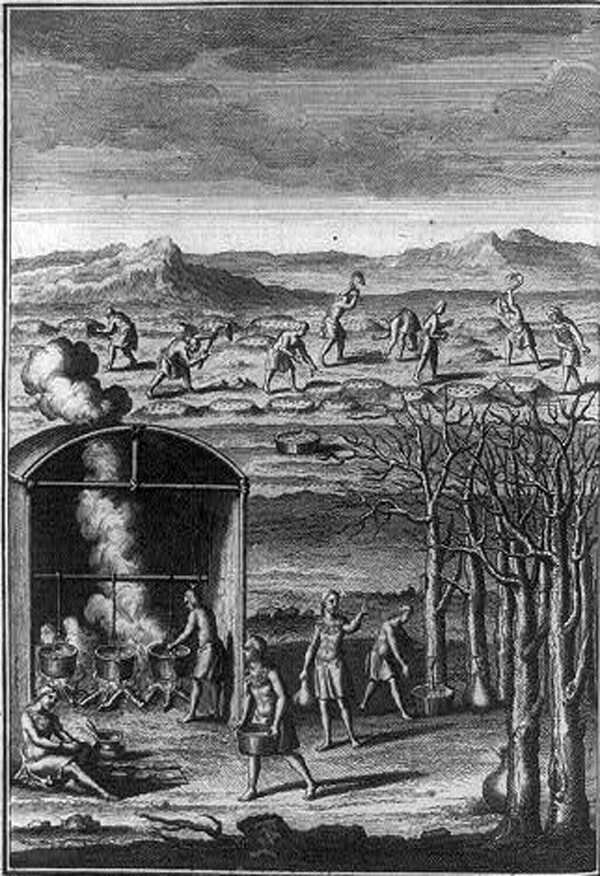

So how did they work out the process of turning sap into syrup into sugar?

We’ve jumped to the boil method using tubs or arches. But if you needed sufficient sugar to preserve foods and add to caloric intake how would you do it? Ten pounds of sugar requires a massive amount of work.

Were wooden spiles used to drip into bark containers?

How were holes drilled? Maybe branches were injured to cause sap drips. (And hope it doesn’t get windy.)

Was freezing used to turn sap to syrup to sugar? (Freezing might get you so far and then evaporation take over?)

The pottery of early people was unglazed, so maybe an unglazed pot on a fire would boil off some water in steam and other water removed by direct transfer out. (I’ve suggested someone try this but without a PHD in Studies I’m a crackpot.)

Spring’s sweetness is in warming weather, in sap, in plant life reviving from death-like appearance. Sweet spring is also found in taking fresh breaths and looking at what we think we know.

Spring is about the future, but tomorrow never arrives minus history of yesterday. As the sap tells of a tree’s past the current dark virus reveals us lofty and conquering humans as creatures easily fearful of unforeseen diseases as we were in the past of unseen spooks or other terrors lurking in the night. Fear can equal in spirit damage what disease can do to the body. Spring is bare ground showing new shoots poking up with no assurance other than hope of a warmer tomorrow

| Tweet |