News & Articles

Browse all content by date.

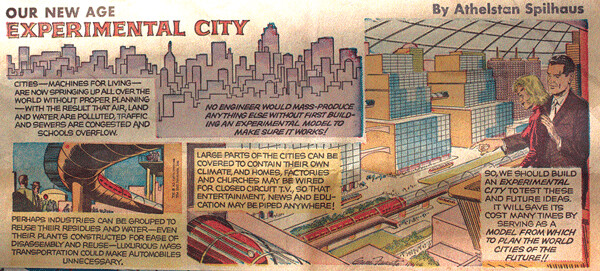

Northern Minnesota was almost home to the world’s first domed city. In the 1960s and ‘70s Athelstan Spilhaus, dean of the University of Minnesota Institute of Technology and author of “Our New Age,” a science feature in the Sunday comics, proposed to build an enclosed city with a population of 250,000 people over 60,000 acres in a remote, swampy area of Aitkin County. Both the federal government and state, eager to be on board with a bold futuristic idea, pitched in to fund planning.

But the changing times turned against the project. It was supported by President Johnson but not by Nixon. Environmentalists once supported high-tech solutions such as nuclear power to pollution and waste, but a newer generation saw them as creating more problems. Wetlands were becoming realized as a resource to be protected rather than as undesirable swamp. The Minnesota Pollution Control Agency took a dim view of the plans. And the residents of tiny Swatara, Minn. marched to the state capitol to keep it our of their backyard.

Images courtesy: mxcfilm.com.

The project has been largely forgotten, but the ideas it raised about innovation, urban planning and a zero-waste society are even more relevant today. It is the subject of a new documentary, “The Experimental City” by Missouri-based filmmakers Chad and Jaime Freidrichs.

Chad Freidrichs was present for a special screening at Zinema in Duluth April 20. After the film, the audience pitched questions to a panel lead by Sharon Moen of Sea Grant at UMD (author of “With Tomorrow in Mind,” a biography of Spilhaus). The panel included Adam Fulton, community planning manager for the City of Duluth, and Tom Beery, resiliency specialist for Minnesota Sea Grant. (The following is just part of the discussion and has been edited for length.)

If they had picked the site in the beginning and then had the local people as part of the committee, do you think that would have worked better?

Freidrichs: They obviously targeted Aitkin County because it was the poorest county in the state, it was felt the jobs would be there, and it would be something that would lure tenants into supporting the project. I listened to about 180 hours of these people talking about this futuristic city and there was a lot of discussion. At what stage do we incorporate the residents? The thinking was, at least among some on the committee, if you allow people to dictate the course of the city prematurely you would, of course, end up with an existing city. There’s a reason why our cities look the way they are and that has to do with the choices people make on the ground level, what they vote for, etc. And so the thinking was this had to at least come from the top down to a certain extent. But there was a lot of sincere discussion about when to incorporate the residents' points of view, how much say they should have and what not. I think it was always going to be a tough sell in any city in Minnesota at the time.

Fulton: The question of citizen input for the urban planning profession has changed a lot. City planning was mostly done by architects, and then it started being done by people who were just doing city planning-type things, and in the ‘20s and ‘30s you saw more and more of that. But you really did see a dramatic change starting in the ‘60s. We don’t think about public participation and engagement the same way they did in the ‘60s. It was sort of a “we know best” kind of thing and I would say that is definitely no longer the case.

Freidrichs: The experimental city ran from ‘66 to ‘73. You go from largely a top-down kind to era to something where grass roots is deeply respected and expected by the time that this project gets started. But the very nature, the conceptualization of it, required a kind of top-down approach, at least initially.

What was their plan to lure 250,000 people?

Freidrichs: Free money, $10 billion. (Laughter) So the plan was the jobs. Like anything, that’s the reason why people move to the Twin Cities, because of jobs, it’s the reason they move to any urban area. I heard them talk endlessly about jobs and the kind of jobs that would go into this city. That was also the mechanism by which the population size would be limited. So 250,000 people at a certain limit, you would cut off the jobs that were available, and that way you could keep the city from growing without literally shutting the doors. The kinds of jobs were either education-focused, or they looked to Columbia, Maryland and Reston, Virginia, and they looked at the kind of jobs that were going there: aerospace, high-tech medicine, light manufacturing of high-tech equipment like Honeywell.

Tom Beery: One of the stats I noticed in the film was 90,000 jobs for 250,000 people. It’s one of those things where there’s economic change and it didn’t really account for that, but still it’s an incredible idea. It probably doesn’t take into account the fact that people age. Are you going to force people, is there going to be a mandatory move-out-of-the-experimental-city age, because you have people who are older who can’t work in those 90,000 jobs? So it’s complicated.

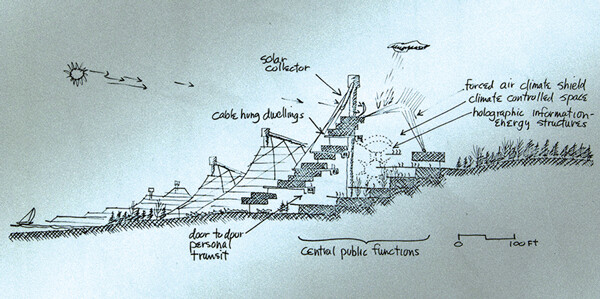

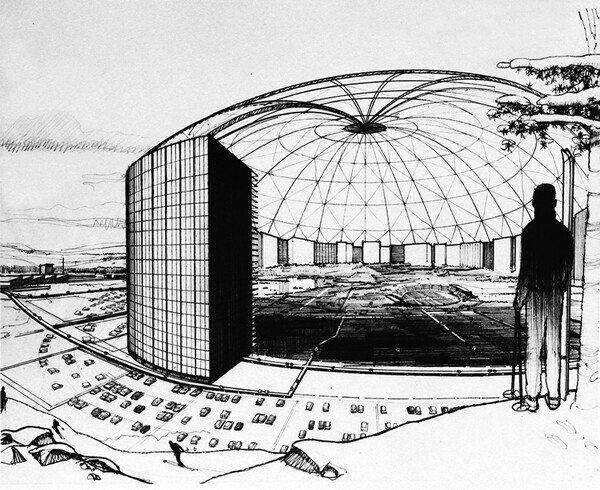

It seems staggeringly science-fictiony. In 1960s and ‘70s technology, was this really feasible?

Moen: Spilhaus’ idea was born because of his work in Seattle. He was appointed to direct the World’s Fair. The United States’ portion was going to be a wild west show, but then all of sudden Sputnik went up and then we were in this war, or this race with Russia, it was like, who’s pre-eminent in science? Then all of a sudden all this money was flowing toward science. At the World’s Fair it became a showcase for American science. And that’s where Spilhaus gathered up all these ideas from creative architects and engineers and researchers and he came back to Minnesota and that’s when he said we need an experimental city. The same time he also said we need a Sea Grant program and that actually happened. (Laughter) It was that time in American history when anything was possible. The Jetsons were on, we were shooting people to the moon, it was gonna be possible. Whether it would have been sustainable, R. Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic domes are starting to collapse in different areas. The experimental part is, we would have to be okay with things not working out and reinventing them and absorbing them back in, recycling them into something new. One of Spilhaus’ ideas was to make buildings like ice cream cones where you can just deflate them and have an empty space, like make stuff out of nothing, almost, and dissolve them.

Freidrichs: People from Bell Labs were participating in this project, these are like profound minds in technology, Nobel Prize winners and such, and you look at the things they predicted, they weren’t too far off in many respects. If you look at the proto-internet that was being proposed in the experimental city, that one totally happened. It happened a little bit slower than what they expected, but the idea was the experimental city would be a kind of catalyst for those kinds of ideas and make them occur more rapidly. A mile-wide dome, that’s probably one that we’re best not to have developed, perhaps. The idea of planning industry so that one’s waste product would be the input of the next waste product, you’re actually starting to see those things, overseas for the most part. We don’t have the same planning power to accomplish something like that in the United States right now. Could you have had a solar-powered city at the time? I don’t think so. You would have had to power this thing nuclear. But in many other respects I think they felt they could pull it off in 10 years. I have no reason to disbelieve them, these were the best experts of the time.

Is there any connection between what came out of this any other experimental cities endeavors? I think of two, Arcosanti in Arizona and Disneyworld. Did this work in any way continue to live on?

Moen: EPCOT is short for Experimental Prototype City of Tomorrow, and that was a contemporary idea with experimental city design. They were born in the same era.

Freidrichs: Athelstan Spilhaus’s very first “New Age” from 1958 is about the mechanism and result of man-made climate change. It actually explains carbon dioxide going into the air, the greenhouse effect, he uses that term, and then the polar ice caps melting, and New York City underwater is the last panel. It’s amazing how in many respects he was prescient. As for Disney and Arcosanti, all of those folks were drinking from a similar kind of well. Walt Disney was working on his EPCOT, which was not the EPCOT we’re familiar with now, it wasn’t an amusement park, it was supposed to be a real-life city. If you look at his plans, you can look on Youtube, it’s almost identical to the experimental city. He’s talking about underground infrastructure, he’s talking about the city itself continually changing and experimenting to help other cities. Walt Disney was doing the exact same things Spilhaus was doing, completely unaware of each other, or at least they were aware of Walt Disney but drawing from the same well of expertise. So that just goes to show these kinds of ideas were current at the time. Actually when Disney died and when the Walt Disney Company started to put together the plans for EPCOT in the early 1970s, they actually came up to Minnesota and met with the folks at the Minnesota Experimental City Project to gain from their experience.

Fulton: Disney did build a planned community, it wasn’t quite as experimental, It was essentially memorialized in “The Truman Show.” Here’s this thing that we did and it’s sort of weird. Planned communities have been around since the time of Rome, this is not a new thing. I think probably a fairly unique idea how, we were trying to apply this technology, but cities are functionally a place where we come to experience technological change together and so we’ll probably continue to see these.

Beery: What I get excited about this is the kind of creativity and innovation that went into those ideas, some that perhaps were well on their way to becoming reality, some that never were realized, but we can cherry pick today and pull out that innovation and look forward. I think its innovation was the exciting part of the story we should use. Our best climate projections right now take us to mid-century. What the best modeling is saying about Minnesota is, we’re going to be warmer in weather, our winters are gonna be warmer, and we’re projected to experience severe precipitation events of unprecedented nature. We don’t know exactly how well our projections are, although our models are getting better and better, but there is some good science that goes into that modeling, and right there, those three challenges, that’s where we should focus all this excitement about cities of tomorrow. And what better place place than Duluth, this city built on a rock and a hill, to think about severe weather events and a wetter, warmer tomorrow, and apply a lot of that innovative thinking to deal with stormwater? I know that’s not as sexy as a bubble and all those things, but that’s where we need this kind of innovation.

“The Experimental City” is currently available only in special showings and for educational use, but eventually will be available on DVD and streaming. Check mxcfilm.com.

| Tweet |