News & Articles

Browse all content by date.

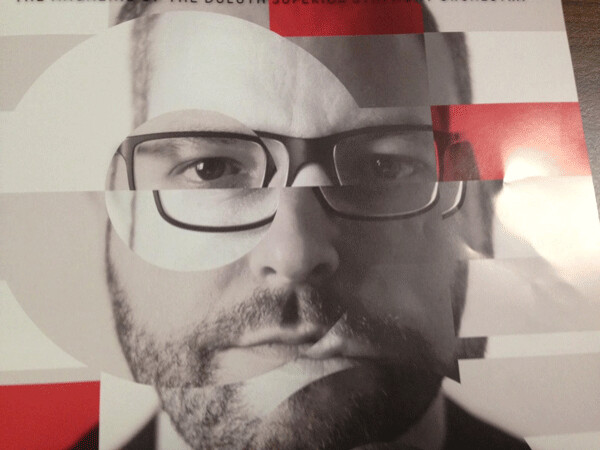

With an opening concert commemorating the explosive issue of revolution, the 2017-18 season of the Duluth Superior Symphony Orchestra began last Saturday night. Music Director/Conductor Dirk Meyer led a rather large orchestra in performance of three pieces of music, each one from a different century. The main floor of the DECC was also quite full for this very satisfying concert.

Ominous Latin Rhythms

Meyer began the energetic evening with a seven minute work for full orchestra by Uruguayan/American composer Miguel del Aguila (b.1957). The Giant Guitar, Op. 91 was commissioned by organizations in Buffalo, NY, and first performed there in June, 2006. Beginning with harp and flute sounds and rhythms reminiscent of the Inca world of the high Andes, the work proceeded rather quickly to the violently percussive memories of the 1970s across many Latin American countries. Even a warning siren is defiantly crushed by the tympani and bass drum. Ironically enough, as Vincent Osborn mentioned in his program notes, a guitar is the only instrument conspicuously absent from the orchestra.

Romantic cascades from a melodic master

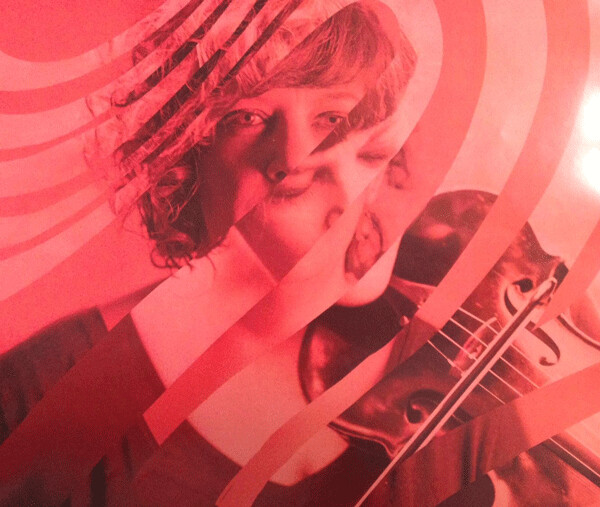

As Symphony Hall gradually ceased its throbbing, several orchestral members took a break as Meyer came back on stage with concertmaster Erin Aldridge, this time in a magnificent soloist role. She joined Meyer in a very passionate performance of the Violin Concerto, Op. 35, composed by Pyotr Tchaikovsky back in 1878. The milder revolution here was the rapid composition (less than one month) and the subsequent rejection by the prominent violinist who was supposed to premiere it. The first audience and critics rejected it as well, but it has become one of the most beloved violin concertos for modern day concert-goers.

The first movement is about drama, as Aldridge powerfully uses her bow and rapid fingering to express emotional, beautiful melodies, and gymnastic exercises on the fingerboard. Meyer uses the orchestra as a very supportive platform for the charismatic presence of the violin soloist. The gentle, exquisite song of the second movement is a well-earned relief for both Aldridge and the listeners in the front rows. Quickly, however, a lively, gypsy dance gets everyone in motion again. With a burst of energy the orchestra gallops to the finish, with Aldridge and her violin holding the reins and riding off into the stratosphere.

In recognition of the long-time musical and financial support of Harris and Diane Balko, a special DSSO thank you was followed by a lovely encore of the Meditation from Thais, an opera by Jules Massenet.

Duluth premiere after fifty six years

Meyer completed his revolution theme by programming the Symphony No. 12, Op. 112, by Dmitri Shostakovich - who named this work The Year 1917. This was the first performance of this symphony by the DSSO, and it was riveting. The four thematic movements are played without an interruption, although the dark melody intoned by the cellos at the beginning returns to commence the fourth section.

Struggle is front and center at all times, as the strings are punctuated (or punctured) by the brass and percussion. The lovely strings that sing pastorally to indicate the second section are interrupted by the insistent trombone (as Lenin plans for the October, 1917, assault). Clarinet, flute, oboe, and bassoon frequently create lovely ensembles, later to be smashed by brass and percussion. All five percussionists were using two hands with great force, as the overwhelming, aggressive, excitement brought the work to a close.

The 1961 premiere in Leningrad was enthusiastic, although Shostakovich knew that many in the audience would certainly understand his more subtle implication that the violent conclusion was ultimately not as beneficial as initially imagined.

Dirk Meyer excelled (again) in his ability to interpret the complicated musical story line to both performers and audience. The lyricism was full and rich, while the sense of doom and futility was both impressive and oppressive.

Over the decades, the DSSO has performed five of the Shostakovich symphonies (1, 5, 6, 9, & 12). There are ten others, and since the composer died in 1975, I would certainly like to hear them live in Duluth. This opening concert, however, was right on target: one living composer, one (still) modern composer, and one amazing chestnut from the past. This is the variety that brings me happily back to the DSSO performances each month.

| Tweet |