News & Articles

Browse all content by date.

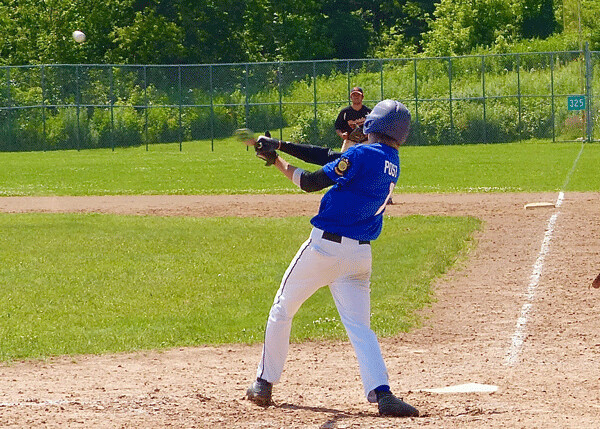

Stopping by Ordean Field to watch a little American Legion playoff baseball last weekend, I couldn’t prevent a few reveries about the way the old Ordean Field used to be, back a few decades when dads and grand-dads of today’s players patrolled those grounds.

We didn’t have anything like a pitch count, or inning count. We had a couple guys who could pitch, and they pitched. If they pitched too much, they threw slower, with more curve balls, to preserve their arms so they could keep pitching. It wasn’t the wisest way to do it, but it was a different era.

Pitching in the current structure is all-important. As the double-elimination Division 1 event unfolded, Lakeview, West Duluth, Grand Rapids and Cloquet emerged as the top teams. Grand Rapids outlasted Nisswa in an elimination game 9-8 last Friday, while the West Duluth Cubs avenged an earlier loss by crushing Lakeview’s undefeated entry 22-5.

The game I watched had Grand Rapids playing West Duluth, and that winner would advance to play Lakeview for the title. All three teams had one loss at that point. But the West Duluth Cubs were thin on pitching. Three pitchers couldn’t contain Grand Rapids, which took an 11-4 lead. But the West Duluth Cubs rallied to make a game of it.

Tanner Ritchie smacked a hit, and the game became 12-8. The Cubs, comprised of Denfeld kids and a couple from Marshall, put a couple of those Marshall standouts to work. With a runner on first, Maddux Baggs cracked a solid line drive to right. Then Derek Winn, the third baseman who pitched Marshall into the state tournament a couple months ago, blasted the a triple to clear the bases and the Cubs had closed to 12-10 with two innings left.

Sadly for West Duluth, Nick Seamon, who had pitched effectively as the third hurler for the Cubs that day, lost his command of hitting the plate, and a couple of walked-in runs, and Tanner Ritchie’s final relief work, couldn’t stop Grand Rapids, which wound up winning 20-10.

That ended the season for the West Duluth Cubs, and sent Grand Rapids on to face Lakeview. If Lakeview was still smarting from that 22-5 whipping the Cubs had inflicted the night before, it was not evident. Now it was Grand Rapids’s turn to be out of pitching, and Lakeview prevailed 16-3 to advance to the state tournament.

It was easy to identify with all sides for a former player. I played baseball in Lakeside, with the kids who would wind up at Duluth East, although living in Lakewood, I was among those who were bused into Duluth to attend Central. East allegedly didn’t have room for those country kids whose Lakewood School had burned down and was rebuilt into Grades 1-6 only.

So I had an interesting perspective of the heated East-Central rivalry, and I participated on both sides of it. Our Zenith City Legion team used Ordean as home field, and today’s players wouldn’t believe what it was like back then. There was no school — high school or junior high — on the premises. Just a gigantic, weirdly angled field.

The grandstand was a huge and solid chunk of concrete, angling behind home plate and around toward right field. The field itself was laid out so that the backstop, near the concrete stands, was about a half-block away. OK, maybe only 75-80 feet, but it was an automatic extra base whenever a throw got away or a wild pitch eluded the catcher.

There was no fence around the outfield, unless you counted that cyclone fence ‘way out there in left field, that ran along and behind a softball field positioned a Miguel Sano-distance home run from the baseball field. That fence went on just about over the horizon, then finally curved back around right field, which housed yet another softball field before heading back toward the concrete stands.

My two greatest moments on that enormity we called a home field came in our first home game against the David Wisted Post. Wisted was the Central kids, the ones I had played with my senior year and which won the District 26 championship, beating East along the way. Dan Howard, the big lefty who played center on the Duluth Central undefeated basketball state champs the following season, threw with blazing speed, and later would go to the University of Minnesota as a pitcher.

Wisted beat our rag-tag Zenith City outfit that day, and I was nothing like the confident hitter I would later become, partly because of that day. I led off and faced the heckles of the rest of the Wisted team as big Dan wound up to blow me away. Something I later used often as a coach was that a good fastball pitcher will always want to throw a first-pitch strike, so be prepared to go for it. Big Dan threw, he was fast, and I was late, but I hit the pitch squarely, down the right-field line -- an opposite-field triple. Of course, I had to act nonchalant, as though I intended to do what Dan Gladden would now claim was “going the other way with it” when a Twins batter swings late.

My other big moment came midseason that summer. Jojo Vatalaro was our manager, and he was a treat. But he was not a tactical coach, and because I was one of the older kids, and already a student of the game, he leaned on me to make out the lineup and suggest position changes. My mother, who worked too much to pay attention to my ballplaying, and my sister attended this midseason game, as did several friends I knew from high school, and the usual neighborhood friends from Lakeside.

I played shortstop, and had my best day batting in all of kid baseball. I hit a double, then later a single to drive in a run. And then I connected with a feeling of exhilaration I can still recall vividly -- a rare perfect swing and a rarer perfect connection on the fat part of the barrel. I ran like I had never run before, circling around first and second, as the ball landed beyond where any normal fence would be. It bounced and rolled into the softball field that was a block or so away (in memory, that is), and I was amazed when I reached third and JoJo was waving me to keep running. A 3-run home run.

My mom and sister congratulated me, but with a manner that made me realize this was the first game they had seen me play, and assumed I must hit like that every game. I had to act nonchalant, of course, and keep the glee from my greatest hitting day bottled up.

The rebuilding of Ordean into a fantastic baseball park, with reasonable outfield fences, an adequate grandstand with a press box, for crying out loud, and dugouts replacing the single bench of the old Ordean ballpark. Every once in a while a pitch got past the catcher, who would whirl around and chase the ball down. It looked so easy, but that's because the backstop was in the same zip-code as home plate. That distant backstop was one of the reasons I talked JoJo into moving from catcher to shortstop. These guys wouldn't believe their eyes if they saw the old Ordean Field.

| Tweet |